The Photograph That Lied: How a 1902 Studio Portrait Exposed a Stolen Child and a Century of Silence

When the leather portfolio arrived at the Massachusetts Historical Society, no one expected it to change history.

It was delivered quietly, like thousands of other donations—objects rescued from estate sales, forgotten attics, collapsing Victorian desks. The portfolio itself was plain: cracked brown leather, tarnished brass clasps, the faint smell of dust and time. Inside, however, rested a studio photograph dated 1902, a type archivists saw almost every day.

And yet, the moment archivist David Morrison opened it, he hesitated.

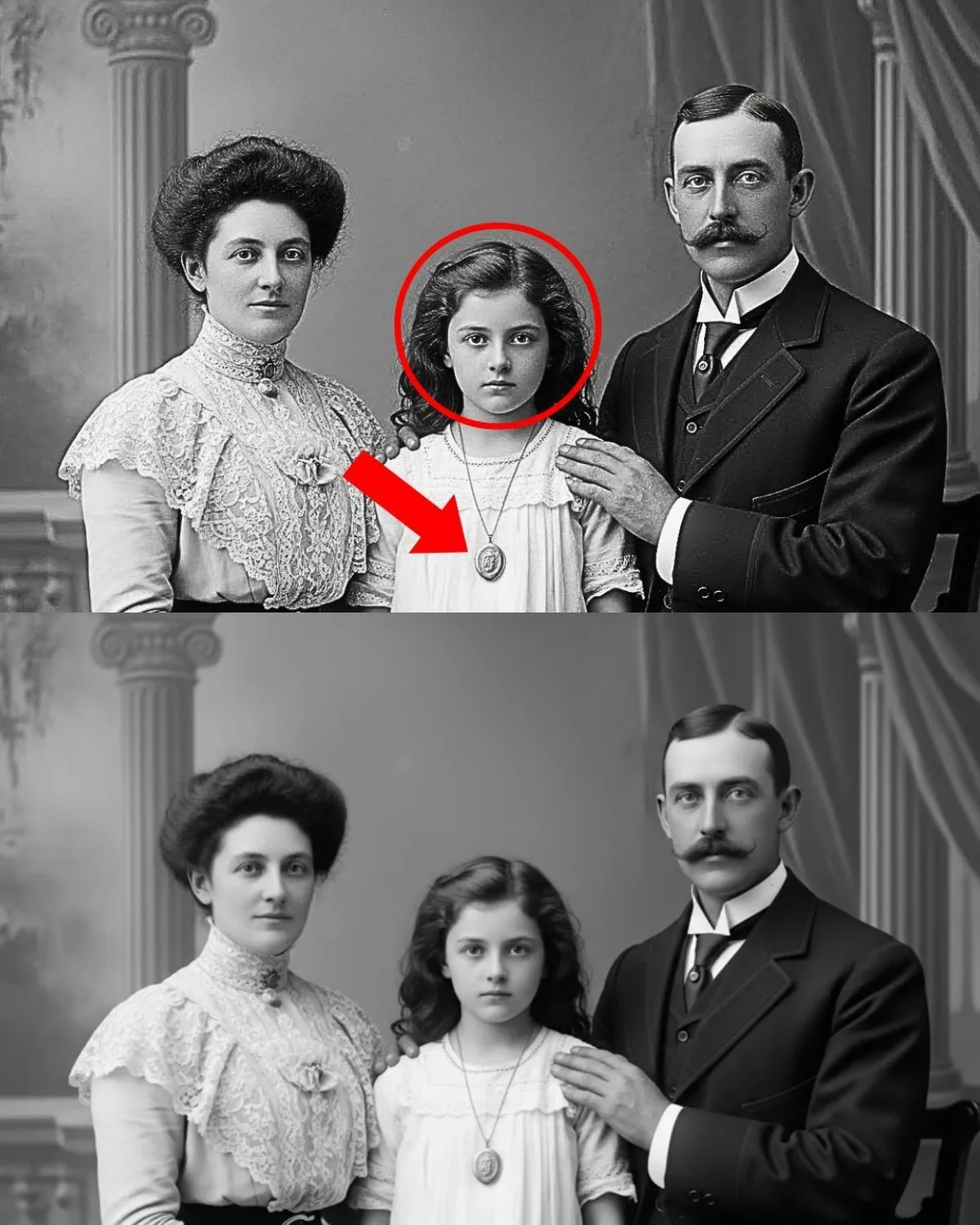

The image showed a well-dressed couple standing stiffly in a Boston photography studio. Between them stood a small girl, no more than six years old. The man’s hand rested on her shoulder. The woman’s lace-trimmed gown flowed elegantly. The painted backdrop—classical columns, draped fabric—was unmistakably turn-of-the-century. The photographer’s mark read: J.P. Whitmore Studio.

It should have been unremarkable.

But something was wrong.

David Morrison had spent his career studying old photographs. He knew the rhythms of these images: pride, prosperity, aspiration. Families used photography to announce themselves to the world. Yet this portrait resisted that reading. The girl stared directly into the camera, her eyes wide and solemn. Her posture was rigid, her small shoulders tense. The adults’ expressions felt rehearsed rather than warm. The image did not feel like memory-making. It felt like evidence.

Three days later, under the glow of a digital restoration monitor, the photograph began to speak.

Working alongside imaging specialist Emma Chen, Morrison authorized a full high-resolution enhancement. As contrast sharpened and shadows lifted, details emerged that had been invisible for more than a century. On the child’s chest hung a small oval locket, engraved with delicate initials: M.R.

Those two letters would unravel everything.

Further enhancement revealed something else—an object never meant to be part of the portrait. In the background, on a studio prop table, sat a framed photograph: a woman holding an infant. It was older than the main image, worn, faded, intimate. Someone had left it there. Or wanted it there.

From that moment, the photograph ceased to be a family portrait. It became a crime scene.

Morrison turned to newspapers from 1902. In the Evening Record, he found a report dated March 15: “Tragic Fire Claims Three Lives in South End—Mother and Two Children Perish.” The victims were listed as Margaret Russell, age 28, her daughter Eleanor, age six, and infant son Thomas.

Margaret Russell.

Eleanor Russell.

M.R.

The locket’s initials matched a child officially declared dead.

What followed was a meticulous reconstruction of a life that had been erased and rewritten. Through railway employment records, property ledgers, studio sitting books, and psychiatric hospital files, a chilling narrative emerged.

The wealthy couple in the photograph were Charles and Catherine Bennett, residents of Back Bay, Boston. They had taken the photograph in October 1902—just months after the Russell fire. Catherine Bennett would later be institutionalized, plagued by guilt, repeatedly telling doctors that the child in her home “was not hers.” Her husband dismissed her claims as delusion.

But Catherine was telling the truth.

Eleanor Russell had survived the fire.

In the chaos of emergency treatment, she was mistakenly recorded as deceased. Charles Bennett, a textile merchant with business ties to the railroad where Eleanor’s father worked, learned of the tragedy. Knowing Eleanor’s mother and brother were dead—and her father believed her dead—Bennett removed the child from the hospital under false pretenses.

He renamed her. He erased her past.

The photograph captured that lie at its beginning.

Years later, Eleanor herself uncovered the truth. In a handwritten letter preserved in boarding school records, she confessed that “Eleanor Bennett” was not her real name. She launched her own investigation, petitioned courts, and reclaimed her identity. She went on to advocate for orphan protections, ensuring no child could be quietly stolen as she had been.

When historians presented the enhanced photograph to the public, the reaction was stunned silence.

The image showed what words never could: a child who did not belong, a woman consumed by guilt, a man exerting control, and a moment frozen at the intersection of grief, power, and deception. The photograph had survived because a photographer sensed something was wrong—but did not yet have language for it.

Today, the portrait hangs with a new plaque. Visitors pause longer than usual. They notice the locket. They notice the tension. They realize they are not looking at a family, but at the visual record of a stolen life.

History did not change because the photograph existed.

History changed because someone finally looked closely enough.