It started as a routine assignment, the kind Margaret Holloway had accepted hundreds of times before without a second thought.

On the morning of March 15th, 2019, she arrived at a Victorian house on Elmwood Street in Portland, Maine, clipboard under her arm, keys jingling softly in her hand. At sixty-seven, Margaret had spent nearly three decades organizing estate sales—cataloging the physical remains of lives that had ended quietly, often without witnesses. She knew the rhythm of these houses well: the smell of old wood and dust, the way silence settled into corners, the feeling that everything important had already happened long ago.

The house belonged to Elellanena Witmore, who had died at ninety-four without any living relatives. She was, according to the lawyer’s file, the last of her family line. The Witmore house had stood since 1887, unchanged in spirit if not in structure, a place where furniture hadn’t moved in decades and memories seemed to cling to the walls.

Margaret worked methodically, room by room. It was on the second floor, in the smallest bedroom—clearly once a child’s room—that she found the chest. Mahogany, antique, locked. The key hung nearby, as if waiting. Inside were documents: birth certificates, marriage licenses, funeral programs. And several leather-bound photo albums, their covers cracked, their pages yellowed and fragile.

She carried the albums to the bed and began documenting them, one by one. Most photographs were exactly what she expected: rigid postures, solemn faces, people dressed for permanence rather than comfort. She recognized names from the Witmore family tree the estate lawyer had provided. Thomas Witmore. His wife Catherine. Their daughter Elizabeth. Their son Thomas Jr.

Then she turned a page and stopped.

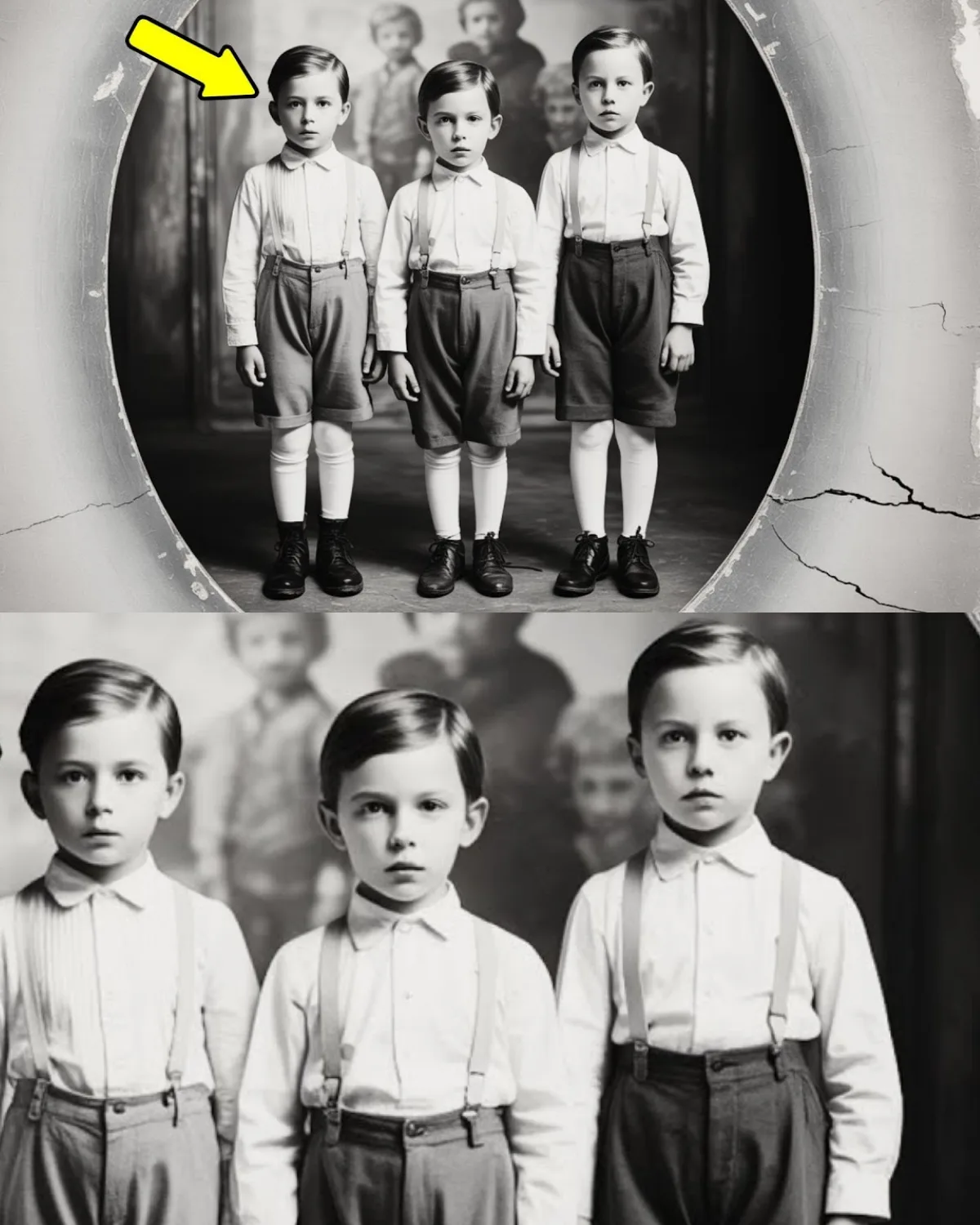

The photograph showed three children, all about eight years old, standing in front of a painted studio backdrop. The image was unusually clear for its age. Two boys and a girl, dressed alike, evenly spaced, solemn in the way children were expected to be solemn in 1909. Beneath the photograph, written in faded ink, was a caption:

Thomas Jr., Elizabeth, and Samuel. Spring 1909.

Margaret felt something tighten in her chest. She reached into her bag and pulled out the Witmore family tree. According to every official record, Thomas and Catherine Witmore had only two children. There was no Samuel. No third child. No footnote, no stillbirth, no death record.

She studied the photograph more closely. The children cast matching shadows. Their shoes were identical. The boy labeled Samuel stood in the same posture as Thomas Jr., hands held in the same way, gaze directed at the camera with the same muted seriousness. This was not a casual addition, not a neighbor’s child slipped into frame. The caption placed him equal to the others.

Margaret searched the rest of the album. Thomas Jr. appeared again and again as he aged. Elizabeth too. Samuel appeared only once. Only here.

Uneasy, Margaret did something she rarely did. She called the estate lawyer, James Thornton, immediately.

Thornton had practiced law in Portland for forty years. He was known for thoroughness bordering on obsession. At first, he dismissed the issue as a clerical error, perhaps a mislabeled cousin. But when Margaret insisted, when she pointed out the precision of the caption and the absence of Samuel anywhere else, Thornton agreed to see it for himself.

By the end of that afternoon, Thornton was no longer dismissive.

He cross-referenced everything. Census records. Birth announcements. Church baptismal rolls. City directories. Every document confirmed the same truth: the Witmore family had only ever officially contained four people. Two parents. Two children. Samuel Witmore did not exist.

And yet the photograph existed.

Thornton’s unease deepened when Margaret discovered a diary among Elellanena Witmore’s personal papers. The entry dated November 12th, 1957—written decades after the photograph—described Elellanena sitting with her father, Thomas Jr., as he lay dying. In delirium, he asked repeatedly, “Is Samuel here?” When Elellanena insisted there was no Samuel, he grew agitated.

Then came the line that changed the investigation entirely:

“We shouldn’t have taken that photograph. Mother said we shouldn’t, but father insisted. He said he wanted all three of his children in one picture. But there were only two of us. Only ever two of us.”

Elellanena wrote that her mother forbade her from ever speaking Samuel’s name again. That her aunt Elizabeth had whispered it once in old age, then denied having done so. The name existed like a bruise—acknowledged only in moments of weakness.

Thornton began to understand that Samuel was not simply missing from records. He had been deliberately erased.

The breakthrough came when they identified the photography studio. Faint embossed lettering on the photograph led Thornton to Walter Harrison, a professional photographer operating in Portland in 1909. Harrison’s studio had closed abruptly in 1913. Thornton traced Harrison’s lineage to a grandson still living near Boston.

Marcus Harrison did not hesitate when Thornton explained why he was calling. He asked to see the photograph immediately. Five minutes after receiving it, Marcus called back and asked Thornton to come in person.

What Marcus shared was his grandfather’s confession.

In a letter written shortly before his death, Walter Harrison described the day the Witmore children were photographed. According to him, Thomas and Catherine Witmore arrived with two children. Nothing unusual. But when Harrison looked through his camera lens, he saw three children standing before his backdrop.

He looked up—there were only two. He looked back through the camera—three again.

He cleaned the lens. Adjusted the focus. Tried again. Each time, the third child appeared only through the camera. Real, solid, indistinguishable from the others.

Harrison took the photograph.

When he developed it, the third child was there.

Thomas Witmore reacted with terror and rage. He demanded silence. He threatened Harrison’s livelihood. He took the photograph and left.

Harrison closed his studio four years later after seeing the same boy again—unchanged, unaged—appear through his camera while photographing another family. He never took another photograph for the rest of his life.

Thornton’s final interview was with Clara Mitchell, Elizabeth Witmore’s daughter. She confirmed what the documents could not explain. Her mother remembered Samuel vividly—playing, eating, existing alongside her and Thomas Jr. Yet in the physical world, there had only ever been two children.

Samuel existed in memory. And in the photograph.

The historical society eventually acquired the image, placing it in a climate-controlled case with a simple label: Whitmore Family Portrait, 1909. No mention of Samuel. No explanation.

But anyone who looked closely could see it.

Three children.

Two documented lives.

And one presence that refused to be erased entirely—as if the camera, in a single moment, had captured something not meant to be preserved, something that had always existed just outside the rules by which families, records, and reality itself are supposed to function.