Disguised as the Enemy

The Execution of Manfred Pernass, 1944

Ardennes, December 1944

The forest was silent in the way only winter silence can be—thick, heavy, unforgiving. Snow covered the ground in uneven drifts, muffling footsteps, dulling sound, and swallowing warmth. Somewhere beyond the trees, artillery thundered without pause, but here, at the edge of a clearing, the war narrowed to a single moment.

A man stood facing a firing squad.

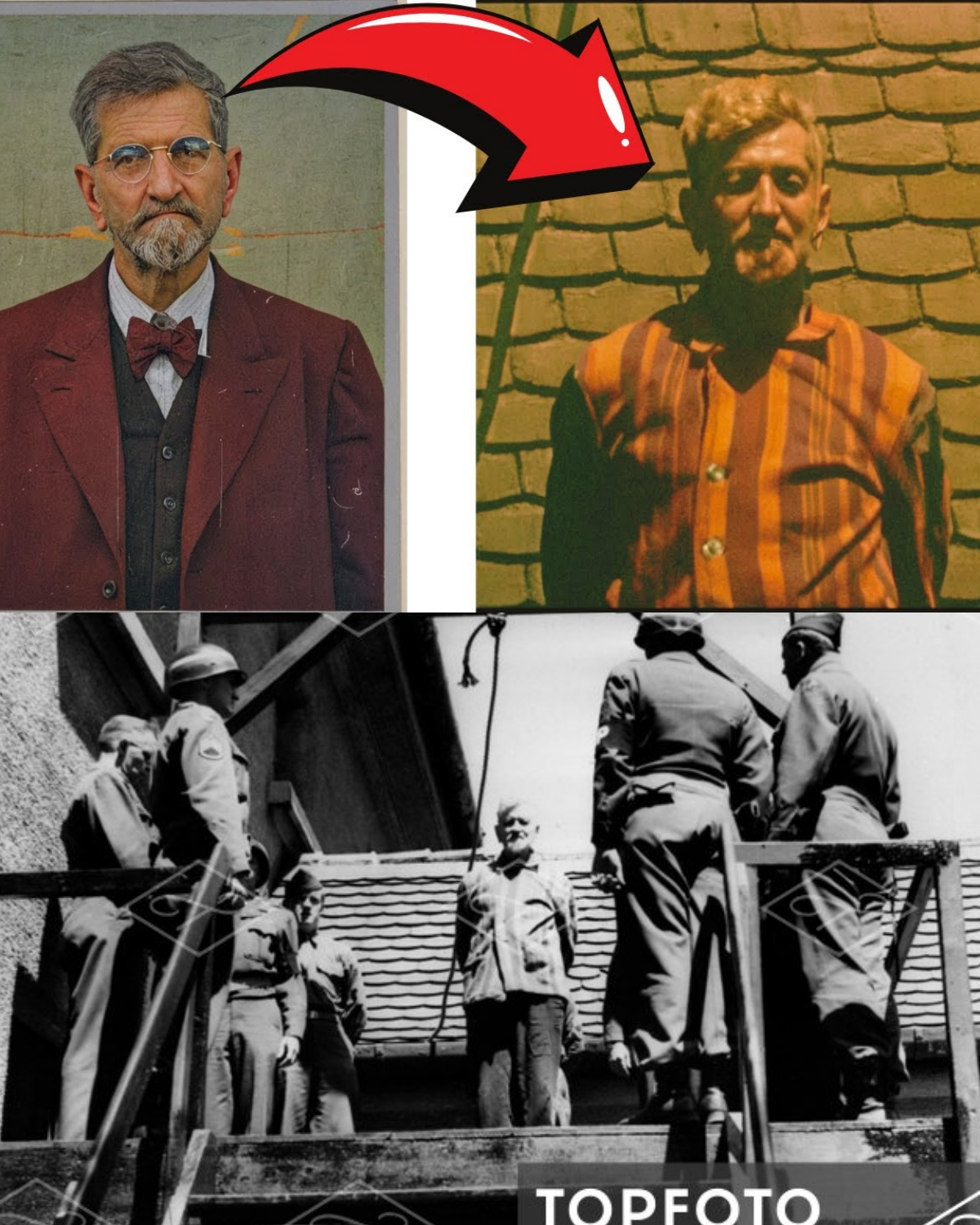

His name was Manfred Pernass. He was not wearing a German uniform. He had not worn one when he was captured either. That fact alone had sealed his fate.

A War of Deception

By December 1944, Nazi Germany was losing the war. Allied forces had broken out of Normandy, liberated Paris, and were advancing steadily toward the German border. The Reich was bleeding men, fuel, and time.

In desperation, Adolf Hitler authorized one final gamble in the west: the Battle of the Bulge.

The plan was audacious—almost delusional. A massive surprise offensive through the Ardennes Forest would split Allied lines, capture fuel depots, and force a negotiated peace. But the success of the operation depended not only on tanks and infantry, but on confusion.

That confusion would be created by men like Manfred Pernass.

Operation Greif

Pernass was selected for Operation Greif, a covert mission conceived by SS commando Otto Skorzeny. Its purpose was psychological warfare.

German soldiers fluent in English were trained to wear American uniforms, drive captured Allied vehicles, change road signs, misdirect convoys, sabotage communications, and spread paranoia behind Allied lines. The goal was not destruction—it was fear.

A single question echoed through Allied ranks: Who can you trust?

Manfred Pernass was one of these men.

A trained paratrooper, he crossed the lines disguised as a U.S. soldier, carrying forged documents and American weapons. Under international law, that choice mattered. Uniforms were not costumes. They were legal boundaries. Crossing them erased protections.

And Pernass crossed willingly.

Capture

The Ardennes offensive created chaos—but chaos cuts both ways.

Allied units, already jumpy from rumors of German impostors, began stopping soldiers at checkpoints. They asked questions no spy could easily answer. Baseball trivia. State capitals. Slang.

Pernass and his comrades did not make it far.

Captured by U.S. forces, they were searched, interrogated, and unmasked. The evidence was undeniable: German soldiers operating in American uniforms, behind Allied lines, during an active offensive.

Under the Geneva Conventions, this was espionage.

Espionage carried only one sentence.

Trial Without Illusion

The trial was brief. It was not theatrical. There were no grand speeches or dramatic revelations. The facts were sufficient on their own.

Pernass had not denied his mission. He had not begged for clemency. He had not pretended to be anything other than what he was.

A soldier sent to deceive.

A spy caught in disguise.

The verdict was foregone: death by firing squad.

There would be no prisoner-of-war camp. No exchange. No second chance.

December 23, 1944

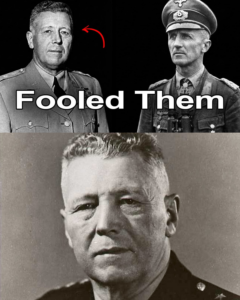

The execution took place just two days before Christmas.

Snow lay thick on the ground. Breath hung in the air. The firing squad—American soldiers, many barely older than Pernass himself—took their positions. For them, this was not vengeance. It was procedure.

Witnesses later recalled that Pernass was calm.

He did not shout slogans. He did not curse his captors. He did not resist. Whether this composure came from discipline, resignation, or shock was impossible to know.

He stood straight.

The command was given.

The rifles fired.

Manfred Pernass fell into the snow, another life ended in a war that devoured men faster than it remembered their names.

Justice or Vengeance?

The execution of German commandos during the Battle of the Bulge remains one of the most morally debated episodes of the Western Front.

From a legal standpoint, the case was clear. Soldiers captured in enemy uniforms while conducting sabotage operations were not protected combatants. They were spies under the laws of war, and spies could be executed.

From a human standpoint, the lines were less clean.

Pernass had not chosen the war. He had been trained, ordered, and deployed by a regime that thrived on obedience. Yet he had also accepted the mission knowing the risk. He understood the rules he was breaking.

This duality—soldier and criminal, pawn and participant—defines his story.

The Fear He Left Behind

Ironically, Operation Greif succeeded in ways its planners never intended.

Even after the commandos were captured or killed, Allied paranoia exploded. Soldiers were detained, questioned, even arrested by their own units. Traffic slowed. Trust eroded. Rumors spread faster than bullets.

Men like Pernass did not change the outcome of the Battle of the Bulge.

But they changed how it felt.

They made the rear feel as dangerous as the front.

A Quiet End

Manfred Pernass did not receive a marked grave. His name does not appear in victory speeches or war memorials. He occupies a narrow, uncomfortable space in history—too guilty to be mourned, too human to be forgotten.

He was not executed for killing civilians.

He was not executed for atrocities.

He was executed for deception.

For pretending to be something he was not, in a war where identity itself had become a weapon.

What Remains

The Battle of the Bulge would fail. German forces would exhaust their reserves and never recover. Within months, Allied armies would cross the Rhine and close in on Berlin.

Pernass would never see that end.

His execution stands as a reminder of an unromantic truth of war: some deaths are not about heroism or cruelty, but about rules—and what happens when they are crossed.

He died not as a prisoner of war, but as a man caught between uniforms, between laws, and between the last desperate gamble of a collapsing regime.

Whether his death was justice or vengeance remains a question history still refuses to answer cleanly.

But on that cold December morning in 1944, the war had already decided for him.