In the winter of 1933, Germany looked like a nation that had already lost a war it had not yet fought. The streets of Berlin were filled with men who no longer bothered to polish their shoes because there was nowhere left to go. Engineers sold apples on corners. War veterans begged for coins outside cafés they could no longer afford to enter.

The memory of the hyperinflation of 1923 still haunted every household: wheelbarrows of money, life savings turned into confetti, a society that had learned, in the most brutal way possible, that paper wealth could vanish overnight. Then came the Great Depression, and with it a second collapse. By the time Adolf Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933, nearly six million Germans were unemployed.

Thirty percent of the workforce had no income. The state was broke, the banks were fragile, and foreign creditors were watching closely. On paper, Germany had no capacity for war. And yet, within six years, that same bankrupt nation would unleash the most formidable military machine Europe had ever seen.

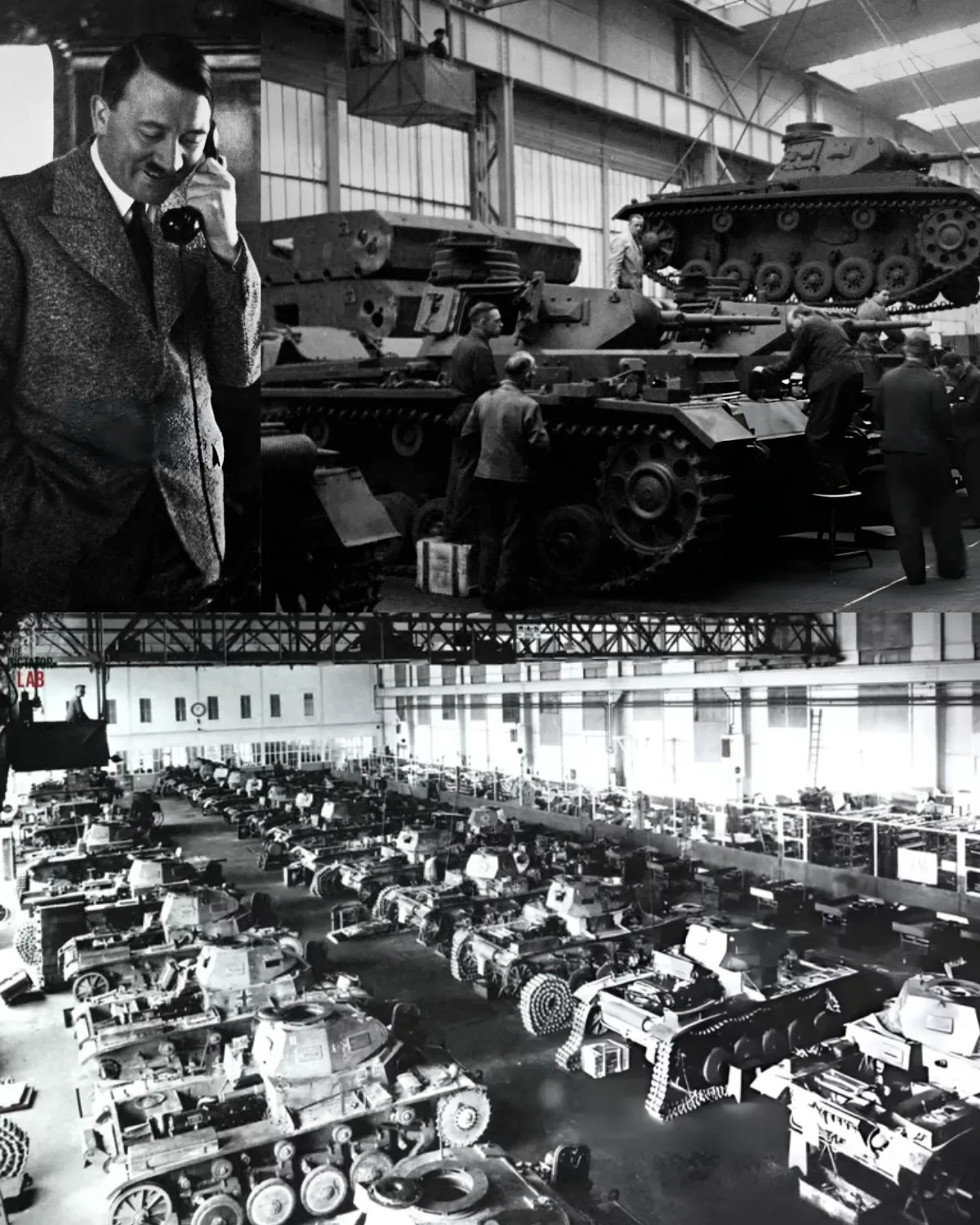

Three million soldiers crossed into Poland in 1939, supported by thousands of tanks, aircraft, submarines, and artillery pieces. To the outside world, it looked like a miracle of economic recovery. To those inside the system, it was something else entirely: a financial illusion so vast, so carefully engineered, that it could only survive by devouring entire countries.

The central question is not simply how Hitler built an army. It is how he did so without money, without credit, and without triggering the very inflation that had once destroyed Germany. The answer lies in a shadow economy that operated parallel to the official state, invisible on paper, yet powerful enough to reshape the continent. At the heart of this system stood a man whose name rarely appears in popular history, but without whom the Nazi war machine could not have existed: Hjalmar Schacht.

Schacht was not a Nazi ideologue. He was a banker, a technocrat, a financial virtuoso who had already saved Germany once. In 1923, when the German mark collapsed into absurdity, Schacht introduced a new currency, the Rentenmark, backed not by gold, which Germany no longer had, but by land and industrial assets. It worked. Inflation stopped almost overnight. Schacht became a national hero. When Hitler came to power a decade later, he needed exactly this kind of mind: someone who could conjure stability out of chaos. In March 1933, Hitler appointed Schacht president of the Reichsbank. In 1934, he became Minister of Economics. His mission was impossible on its face: finance massive rearmament without money, without inflation, and without alerting the world.

Hitler’s dilemma was fundamental. Rearmament meant paying steel companies, aircraft manufacturers, shipyards, chemical plants. That required cash. But if the Reichsbank simply printed money, two things would happen immediately. First, inflation would return, and Germans, traumatized by 1923, would revolt. Second, those expenditures would appear on official balance sheets, and foreign governments would see exactly what Germany was doing. Rearmament had to be invisible. Not hidden in secrecy, but hidden in accounting itself. Schacht’s solution was one of the most audacious financial constructions ever attempted by a modern state.

In 1934, Schacht created a company called Metallurgische Forschungsgesellschaft, abbreviated as MEFO. On paper, it was a private research firm. In reality, it had no employees, no factories, no products. It existed only as a legal shell. Four major industrial giants—Siemens, Krupp, Rheinmetall, and Gutehoffnungshütte—held symbolic shares. Its capitalization was trivial. But MEFO would become the largest financier of war in European history.

Here is how the mechanism worked. When an arms manufacturer delivered tanks or aircraft to the German government, it did not receive cash. Instead, it received MEFO bills—essentially IOUs issued by this fake company, promising payment in five years. The manufacturer needed money immediately to pay workers and suppliers, so it took these bills to a private German bank. The bank accepted them, because everyone understood that behind MEFO stood the Reich itself. The bank gave the manufacturer real cash. Then the bank took the MEFO bills to the Reichsbank and had them converted into money. The critical trick was this: because MEFO was technically a private company, these transactions did not appear as government debt or central bank financing. Officially, they were just private commercial obligations.

Between 1934 and 1938, Germany issued more than twelve billion Reichsmarks in MEFO bills. For comparison, Germany’s entire national debt in 1932 was around ten billion. In less than five years, Hitler secretly created more hidden debt than the state had accumulated in its entire previous history. And yet, on paper, Germany looked fiscally disciplined. Inflation remained low. Foreign observers saw no massive military spending. The illusion worked perfectly.

But MEFO was not money. It was deferred reality. Each bill matured after five years. The first ones, issued in 1934, were due in 1939. And Germany did not have the funds to repay them. Schacht knew this. By 1937, he was warning Hitler that the economy was overheating, that rearmament was unsustainable, that a crisis was inevitable. His reports spoke of looming inflation, shortages, and the impossibility of balancing the budget. Hitler ignored him. In January 1939, weeks before the first MEFO bills came due, Schacht submitted one final desperate memorandum urging drastic cuts. Hitler fired him as head of the Reichsbank.

The financial machine Schacht had built was now fully in Hitler’s hands. And Hitler’s solution was not to repay the debt. It was to feed it.

This is the point where economics and conquest merge into a single logic. A normal state pays its debts with taxation or growth. Nazi Germany paid its debts with plunder. In March 1938, Germany annexed Austria. Overnight, it seized Austrian gold reserves, foreign currency, and industrial assets. In September 1938, it took the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia. In March 1939, it occupied the rest of the country, including the Skoda arms works, one of the most advanced weapons manufacturers in Europe. Then came Poland, with its land, labor force, agriculture, and raw materials. Each conquest provided exactly what the financial system required: fresh resources to service old promises.

The structure now resembled a classic Ponzi scheme. Early obligations were paid with new inflows, but the inflows came not from investors, but from conquered nations. As long as Germany kept expanding, the system worked. The moment expansion stopped, it would collapse. War was no longer a political choice. It had become an economic necessity.

And MEFO was only the beginning. The Nazi economy layered additional mechanisms of extraction on top of this foundation. Occupied countries were forced to pay for their own occupation. France, after 1940, was compelled to transfer hundreds of millions of francs per day to Germany. These payments funded German soldiers stationed in France and subsidized the German war effort. In Eastern Europe, plans were even more explicit. The invasion of the Soviet Union was conceived not only as a racial and ideological war, but as an economic one: Ukraine’s grain, the Caucasus oil fields, and Soviet labor were to sustain the German empire.

Then there was forced labor. Millions of prisoners of war, civilians from occupied countries, and concentration camp inmates were turned into slaves. They worked in factories, mines, and farms, producing weapons, coal, steel, and ammunition. Companies like IG Farben built entire industrial complexes next to camps such as Auschwitz to exploit this labor. Workers were fed barely enough to survive. When they died, they were replaced. This was not a side effect of war. It was the economic core of the system. Genocide and production became structurally linked.

Even German citizens were not spared. The famous Volkswagen program promised ordinary Germans a “people’s car” if they saved monthly contributions. Hundreds of thousands paid into the scheme. Not a single civilian car was ever delivered. The factory was converted to military production. The savings vanished into the war economy. German families, who believed they were investing in a peaceful future, were unknowingly financing conquest.

Foreign loans were treated the same way. In the 1920s, Germany had borrowed heavily from Britain, France, and the United States under the Dawes and Young Plans. Hitler stopped paying reparations in 1933, but kept the money. When Germany invaded France in 1940, the Vichy regime forgave part of the debt. Germany had effectively used Allied money to build the army that defeated them.

By 1939, the Nazi economy was no longer a state. It was a machine that consumed territory. Its survival depended on continuous expansion. Without new victims, it would implode under its own hidden obligations. This is why retreat was unthinkable. This is why compromise was impossible. Peace would have meant bankruptcy, unemployment, and political collapse. War was not merely Hitler’s ideology. It was the only way the system could continue to function.

Historians sometimes debate whether World War II was inevitable. In economic terms, for Nazi Germany, it almost certainly was. The regime had constructed a structure that could not exist in equilibrium. It required perpetual motion: new resources, new labor, new wealth extracted from others. When Germany stopped winning after 1942, the entire model unraveled. Losses could no longer be replaced. Plunder dried up. The same hidden debts that had built the war machine now consumed it. Inflation returned. Shortages spread. Cities were bombed. Slave labor could not compensate for strategic defeat.

In the end, the Nazi economy collapsed exactly as Schacht had predicted. The pyramid ran out of victims.

The disturbing lesson is not just about Hitler. It is about the power of financial illusion. For six years, Germany appeared to the world as a nation that had recovered from catastrophe through discipline and genius. In reality, it was running one of the largest economic frauds in history, disguised as national revival. The tanks that rolled into Poland were financed not by prosperity, but by promises that could only be kept through theft and violence. The war did not begin when the first shots were fired. It began the moment Germany chose to replace economic reality with accounting fiction and discovered that the only way to sustain that fiction was to conquer the world.