March 17th, 1941. 03:07 hours. The North Atlantic is a black, moving desert, its surface broken only by the pale outlines of forty-one merchant ships forcing their way eastward through waves the height of small buildings. On the bridge of HMS Walker, Commander Donald McIntyre stands rigid, his gloved hands locked around a frozen steel railing. Every instinct tells him what his instruments cannot prove: somewhere beneath this convoy, at least five German U-boats are circling in silence, waiting. He cannot see them. He cannot hear them. But he knows they are there, because the Atlantic has taught him what that feeling means. It means men will die before dawn.

What McIntyre does not know, what the Admiralty in London does not know, is that within the next six hours two of the most lethal submarine commanders in the world will be removed from the war, not by new technology, not by superior numbers, but by a modification to a weapon the Royal Navy itself has declared illegal.

To understand how that night became possible, one must first understand the scale of failure that preceded it. In 1940 alone, German U-boats sank 471 Allied ships. Over 2.5 million tons of food, oil, steel, ammunition, and civilian cargo disappeared beneath the Atlantic. Britain, an island nation, imported more than 60 million tons of supplies each year to survive. By early 1941, reserves had dropped to six weeks. The mathematics were no longer abstract. They were existential. At the current rate of losses, Britain would not lose the war by invasion or bombing, but by starvation.

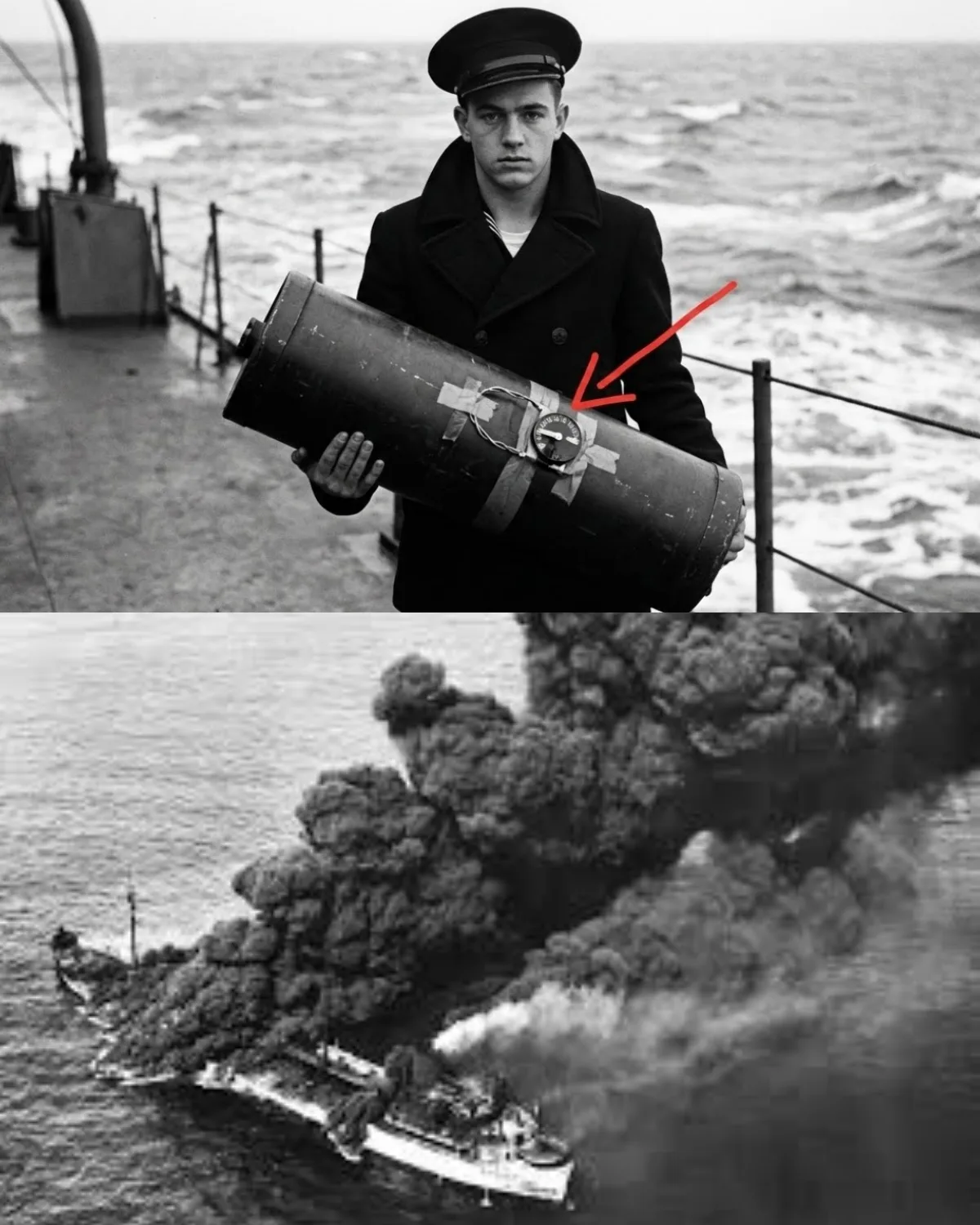

The Royal Navy’s primary defense was the depth charge. A simple weapon in theory: a steel barrel packed with 300 pounds of TNT, dropped off the stern of a destroyer, set to explode at a predetermined depth. Sonar operators detected the submarine, the destroyer accelerated, passed over the contact, and released the charges in a standardized geometric pattern. The explosion was supposed to crush the submarine’s pressure hull, or at least force it to surface.

The official kill rate: three percent. Three out of every hundred attacks resulted in a confirmed sinking. In any other context, this would be considered catastrophic failure. In the Admiralty, it was accepted as “operationally adequate.” Senior officers reviewed the statistics and concluded that depth charges were functioning as designed. Technological limitations, they argued, made major improvements impossible without entirely new weapon systems, which would take years to develop. Doctrine was established. Patterns were fixed. Settings were standardized. No further modifications would be entertained.

And then there was Frederick John Walker.

Walker was not a scientist. He had no laboratory. He had no advanced degree. He had no official authority to modify anything. What he had was a small cabin aboard HMS Stork, a stack of notebooks filled with calculations, and a reputation for asking questions that made superiors uncomfortable. By 1941, Walker’s naval career had stalled. Born in Plymouth in 1896 into a family with three generations of naval service, he had joined the Royal Navy at thirteen, served with distinction in World War I, and earned command in his early thirties. By every conventional metric, he should have been an admiral by forty. Instead, he was still a lieutenant commander, assigned to escort duty, watching U-boats escape while his peers received promotions.

The problem was not incompetence. Walker’s seamanship was exceptional. His tactical mind was sharp. The problem was his refusal to accept doctrine without understanding it. In training exercises, he questioned patrol patterns. In staff meetings, he challenged damage assessments. In 1937, he submitted a forty-page analysis of convoy defense that contradicted Admiralty policy. The response was polite and devastating: his observations were “noted” but “beyond his current scope of responsibility.” Translation: follow orders.

But Walker did something few frustrated officers ever do. He studied his failures. After every unsuccessful depth charge attack, he interviewed sonar operators, measured time delays, reconstructed probable submarine movements. He collected reports not only of rare successes, but of constant failures. Slowly, patterns emerged.

The critical number was thirty seconds.

That was the average time between the moment a destroyer lost sonar contact during its high-speed attack run and the moment depth charges were released. Thirty seconds of blindness. Walker began asking what a submarine could do in thirty seconds. He found the answer buried in technical manuals: a Type VII U-boat executing a crash dive could descend at approximately 280 feet per minute. In thirty seconds, it would pass through the depth band between 50 and 150 feet. And that was the fatal irony. Standard depth charge settings were 150 and 300 feet. The Navy was detonating its weapons exactly where the submarine was not.

Even worse, German commanders had learned this. The moment they heard a destroyer’s propellers, they dived sharply and turned aggressively, exiting the predicted engagement zone before the charges detonated. The carefully calculated diamond patterns assumed straight-line movement. U-boats did not move in straight lines. They twisted, dove, and vanished.

Walker did the mathematics. A submarine turning ninety degrees at six knots would travel roughly 200 yards in thirty seconds. The standard pattern covered a circle barely half that size. The probability of a U-boat still being within the kill zone when the charges exploded was less than ten percent.

The conclusion was inescapable. The depth charge itself was not the problem. The way it was being used was.

Walker submitted a proposal. It was rejected. He revised it, adding calculations and probability models. Rejected again. A third submission was returned with a final stamp: no further correspondence on this matter would be entertained.

What Walker did not know was that his rejected proposal landed on the desk of Commander Gilbert Roberts, head of the Western Approaches Tactical Unit, a secret British war-gaming division operating out of a basement in Liverpool. Roberts ran simulations using wooden models pushed across a painted map of the Atlantic. When he tested Walker’s method against standard doctrine, the results were stark: kill rate increased from four percent to eleven percent.

Roberts took the results to Admiral Sir Percy Noble, commander-in-chief of Western Approaches. Noble did not call a committee. He did not request further studies. On February 28th, 1941, he issued a private memorandum authorizing escort commanders to experiment with tactical variations without prior Admiralty approval. It was a bureaucratic loophole that effectively legalized disobedience.

Walker received the memo on March 3rd. He began with the simplest possible change: depth settings. Instead of 150 and 300 feet, he ordered 40 percent of charges set to 50 feet, 40 percent to 100 feet, and 20 percent to 200 feet. A vertical kill zone, not a horizontal guess.

The first test produced no confirmed sinking, but sonar recorded sounds never heard before: pressure hull deformation, internal flooding, structural failure. Forty-eight hours later, Walker received a direct order: cease all non-standard depth charge settings immediately. His innovation was officially banned.

The confrontation that followed in Liverpool felt less like a military briefing than a trial. Admiralty representatives accused Walker of violating the Naval Discipline Act. He stood at attention and replied calmly that the standard settings did not work. The room erupted. One officer cited forty-seven U-boat kills using standard procedures. Walker responded with the larger number: 1,370 contacts, forty-seven kills. A success rate of 2.6 percent.

He presented his calculations. Type VII submarines passed through the shallow zone during the blind thirty seconds. That was precisely where the Navy was not detonating its weapons. A weapons specialist argued that shallow charges endangered the attacking ship. Walker replied with measured precision: the charges detonated 200 yards astern; the ship’s propellers were fifteen feet below the waterline forward. There was no overlap.

Commander Roberts presented the simulation data: projected kill rate improvement of 278 percent.

Silence followed.

In the end, Admiral Noble authorized six months of field testing. If Walker’s methods failed, they would be abandoned and he would face disciplinary action. If they succeeded, they would be implemented fleet-wide.

Sixteen days later, on the same night the story began, Walker’s method met reality.

U99, commanded by Otto Kretschmer, the most successful U-boat ace in history, had already sunk forty-four ships. For three hours, McIntyre’s group had chased him without result. Then McIntyre ordered a coordinated attack. One ship maintained slow-speed sonar contact. Walker adjusted his approach in real time. At three hundred yards, he released depth charges set to multiple depths.

The water did not erupt in white plumes. It turned black with oil. Debris surfaced. Then U99 broke the surface, hull fractured, flooding uncontrollable. Kretschmer surrendered.

Forty-five minutes later, U100, commanded by Joachim Schepke, the second-highest scoring ace, was forced to surface and rammed in half. Two legends destroyed in one night using tactics the Admiralty had banned.

The ban quietly disappeared.

By the end of 1941, the Royal Navy’s kill rate had more than doubled. Walker continued refining his methods, then developed something even more effective: the “creeping attack.” One ship maintained distant sonar contact. The other shut down engines and crept forward at minimal speed, guided by radio, silent as a ghost. The submarine never heard the attack until the explosions arrived.

In May 1943, during what German sailors called “Black May,” forty-one U-boats were destroyed in a single month. Admiral Dönitz withdrew his fleet from the Atlantic.

Walker died in 1944 at forty-eight years old, of a cerebral thrombosis caused by exhaustion. He had spent eighteen months almost continuously at sea. He never became an admiral. Never received a knighthood. Never commanded anything larger than an escort group.

The Navy adopted his methods but never forgave his defiance. Official records remain silent, but historians agree his career stalled precisely when he began questioning doctrine.

Total U-boats sunk using Walker’s tactics: approximately 147. Estimated lives saved: between ten and fifteen thousand.

On his gravestone in Liverpool, chosen by his crew, there is no mention of tactics, statistics, or rank.

It reads simply: He was the best of us.

And in the cold arithmetic of war, that may be the most dangerous kind of man there is: not the one who follows the rules, but the one who looks at failure and refuses to accept that it is normal.