It began, as many investigations do, with an object that refused to stay ordinary.

In March of 2019, Robert Chen had already spent most of his adult life surrounded by the debris of other people’s pasts. His antique shop on Maple Street in Salem had been open for more than forty years, long enough for every piece that entered its door to feel interchangeable—chairs that once held arguments, jewelry once worn to funerals, photographs whose subjects no longer had names. Robert had learned to handle history the way one handles fragile glass: carefully, but without sentiment. Objects were objects. Meaning belonged to the living.

That assumption fractured quietly on a rain-soaked afternoon, when the contents of the Whitmore estate arrived.

The Whitmore mansion had loomed at the edge of Salem since 1885, a relic of shipping wealth and inherited isolation. Its last resident, Clarence Whitmore, had died three years earlier without heirs, leaving the house sealed and untouched until the estate sale finally dispersed its contents. Robert expected the usual—aesthetic remnants of prosperity stripped of context. What he found instead was a leather portfolio buried beneath moth-eaten linens and tarnished silver.

Inside were approximately thirty photographs from the early 1900s. Robert sorted them with the practiced detachment of a man who had done this thousands of times before. Family portraits. Landscapes. Children stiffly posed in Victorian gardens. All familiar. All forgettable.

Then he reached one image that made him stop.

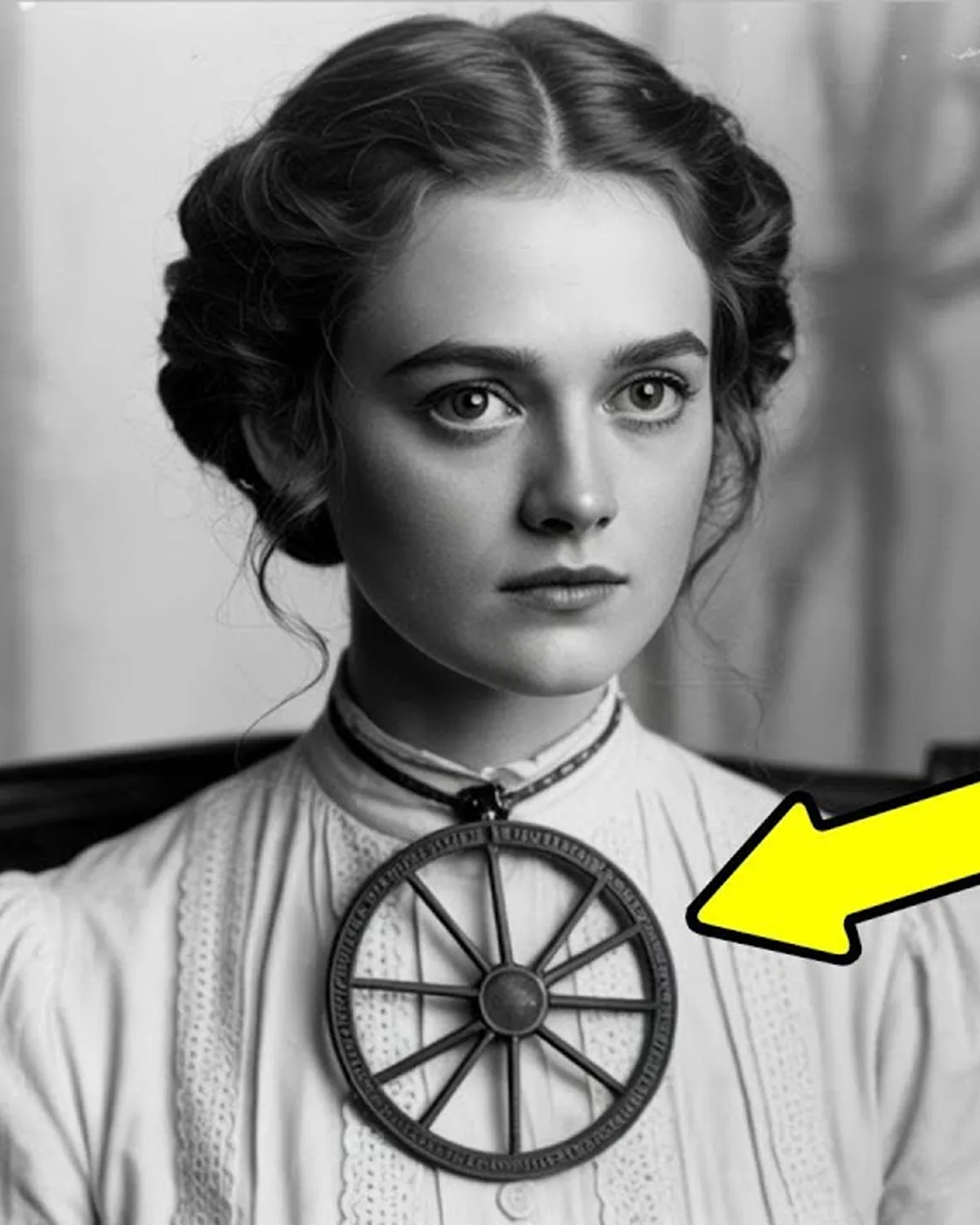

It was a studio portrait of a young woman, likely in her early twenties, seated against a plain backdrop. The technical quality was excellent for its era—balanced lighting, sharp focus, a deliberate composition that suggested a professional photographer rather than a casual sitter. She wore a high-necked white blouse trimmed with lace. Her dark hair was arranged in the Gibson Girl style fashionable around 1910. Nothing about the photograph violated historical expectations. And yet Robert felt a faint but persistent unease, the kind that did not announce itself as fear so much as misalignment.

He set the photograph aside and continued working, but throughout the day his attention drifted back to it. The woman’s expression was serene, almost contemplative, her dark eyes steady and unblinking. She did not appear anxious, nor posed. If anything, she seemed settled—too settled. Robert could not articulate why that disturbed him.

That evening, almost casually, he posted the image to his shop’s social media page with a simple caption asking if anyone recognized the studio or the subject. The response was immediate and disproportionate. Within hours, the post had been shared hundreds of times. Comments poured in, but they were not attempts at identification. They all asked the same question.

What is she wearing?

Robert returned to the photograph with a magnifying glass. Around the woman’s neck was a delicate chain, nearly invisible against the white lace of her blouse. Hanging from it was a circular pendant, small but unmistakable once seen. The metal appeared tarnished, possibly silver or pewter. What drew the eye was not the material, but the design etched into its surface.

It resembled a wheel or compass, but the spokes radiating from the center were uneven, irregular, almost intentionally distorted. Around the outer edge were markings—too deliberate to be decorative, too unfamiliar to be recognized as letters. The longer Robert studied it, the more his discomfort grew. This was not jewelry made to please the eye. It was made to signify something.

Robert contacted his daughter, Emily, a graduate student in American history at Boston University. She arrived that weekend with equipment borrowed from her university’s digital imaging lab. They scanned the photograph at high resolution and enhanced the image using archival software normally reserved for museum conservation.

What emerged was not clarification, but escalation.

The markings around the pendant’s edge appeared deliberate, possibly glyphs from an unfamiliar symbolic system. The spokes, when isolated and overlaid, revealed secondary shapes embedded within the larger design. This was not mass-produced ornamentation. The irregularity suggested hand engraving—careful, intentional, and time-consuming. Someone had gone to considerable effort to create this object.

Emily photographed the back of the original print. There was no studio stamp, no embossed mark. Only a faint pencil notation: “E.H. – June 1910 – Boston.”

Over the following weeks, the photograph spread beyond Robert’s control. Paranormal websites seized on it. Amateur historians debated it in online forums. Some claimed the symbol matched occult imagery from various traditions. Others dismissed it as an obscure but mundane piece of period jewelry. What no one could do was identify the woman, explain the symbol, or justify why it would be worn so prominently in a formal portrait.

The image eventually reached Dr. Margaret Ashford.

Ashford had spent more than thirty years studying American Victorian and Edwardian photography. She had seen hoaxes before, modern fabrications disguised by artificial aging. When a colleague forwarded her the viral photograph, her initial response was skepticism. But professional curiosity outweighed caution, and she requested the original high-resolution scans.

The photograph passed every test. The paper stock, the albumen print process, the tonal range—everything aligned with professional portrait photography from roughly 1908 to 1912. There was no evidence of manipulation, no sign of reproduction. This was a genuine artifact.

Ashford began methodically. She catalogued photography studios operating in Boston in June 1910, cross-referencing them with surviving archives. Most established studios marked their work, but smaller operations did not always do so, particularly if prints were purchased directly. The absence of a stamp was unusual, but not impossible.

The initials presented a larger problem. E.H. could refer to the subject, the photographer, or an intermediary. Ashford combed census records, city directories, and newspapers from the period, compiling lists of women whose initials matched and whose age approximated the subject’s appearance. There were dozens. Without corroborating evidence, none could be confirmed.

As the identification stalled, the symbol became the focal point of the investigation. Ashford consulted colleagues in religious studies, anthropology, and decorative arts. She sent enhanced images to experts in Victorian jewelry. Professor David Winters, a scholar of comparative religion, examined the symbol closely and reached a tentative conclusion. The circular design echoed motifs found across cultures—sun wheels, compasses, cycles—but the specific markings were unplaceable. More importantly, the design was deliberate. This was not symbolic pastiche. It was internally consistent.

Ashford expanded her inquiry to historians of American spiritualism and occult movements. One specialist noted that early twentieth-century Boston was a nexus of esoteric activity. Hermetic societies, Masonic lodges, theosophical groups, and countless smaller organizations flourished during that period. Yet even among these traditions, the symbol could not be definitively matched. It appeared to borrow elements from several systems without belonging fully to any of them.

The investigation took a decisive turn when Ashford examined the photograph under infrared imaging. Faint markings emerged on the studio backdrop—symbols similar to those on the pendant, invisible in normal light. The implications were unsettling. The symbol was not incidental. It was embedded into the photograph itself.

At the same time, Robert Chen researched the provenance of the Whitmore estate. The family’s history was well documented. Edmund Whitmore, the mansion’s original owner, had traveled extensively through Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Asia in the late nineteenth century. His journals, preserved by the Salem Historical Society, revealed sketches of symbols encountered abroad. One page contained a drawing nearly identical to the pendant, accompanied by a note describing a “brotherhood of the eternal cycle” encountered in Istanbul in 1897.

Ashford’s research intensified after she was contacted by Grace Morrison, a retired librarian whose great-great-grandmother had kept a diary in Boston during 1910. The diary referenced a woman named Eleanor Hartley—called Elellanena in the entries—who wore a troubling pendant and attended mysterious meetings. The entries documented Eleanor’s growing detachment, her sudden disappearance in the summer of 1910, and a visit from an unidentified man carrying a photograph of her wearing the symbol.

Newspaper archives confirmed that an unidentified woman had been found in Boston Harbor in December 1910. Additional cases of young women disappearing under similar circumstances surfaced between 1909 and 1911. None were officially linked, but the patterns were difficult to ignore.

Letters from Edmund Whitmore provided further context. In coded language, they referenced “the work,” initiation, and sacrifice. One letter explicitly mentioned E.H., noting her faithful service and the cost of understanding.

A genealogical investigation traced Eleanor Hartley’s life to a factory fire that killed her parents, her relocation to Boston, and her disappearance from official records after June 1910. Her brother, Thomas Hartley, later wrote of receiving a letter claiming Eleanor had “crossed over.” He spent years searching for others who had lost family members to the same symbol, the same promises.

Decades later, Thomas reportedly encountered a woman in New York who resembled his sister but did not recognize him. Records from Greenwich Village revealed the presence of a group called the New Cycle in the 1940s—philosophers interested in consciousness and altered states. They disbanded after a death ruled accidental.

A death certificate from 1969 listed an Elellanena Hartley in Providence, Rhode Island. No relatives. An unmarked grave.

Ashford compiled her findings into a report exceeding two hundred pages. It suggested the existence of a loosely organized movement spanning multiple cities and decades, identifiable by a single symbol. The group’s practices appeared focused on consciousness transformation. For some participants, the transformation was irreversible.

When Ashford presented her work publicly, reactions were divided. Some praised her rigor. Others accused her of indulging speculation. After one lecture, an elderly professor quietly told her about a woman he once knew—reclusive, perceptive, wearing a hidden pendant with an unfamiliar symbol. Her landlord had called her Miss Hartley.

Today, the photograph remains in Robert Chen’s shop, protected behind museum glass. Visitors describe feeling unsettled when they look at it for too long. The image itself is unremarkable by objective standards. The woman is composed. The lighting is correct. The pose is conventional.

And yet there is something in her gaze—steady, knowing, unburdened—that suggests the photograph did not capture a moment before tragedy, but a moment after a decision had already been made.