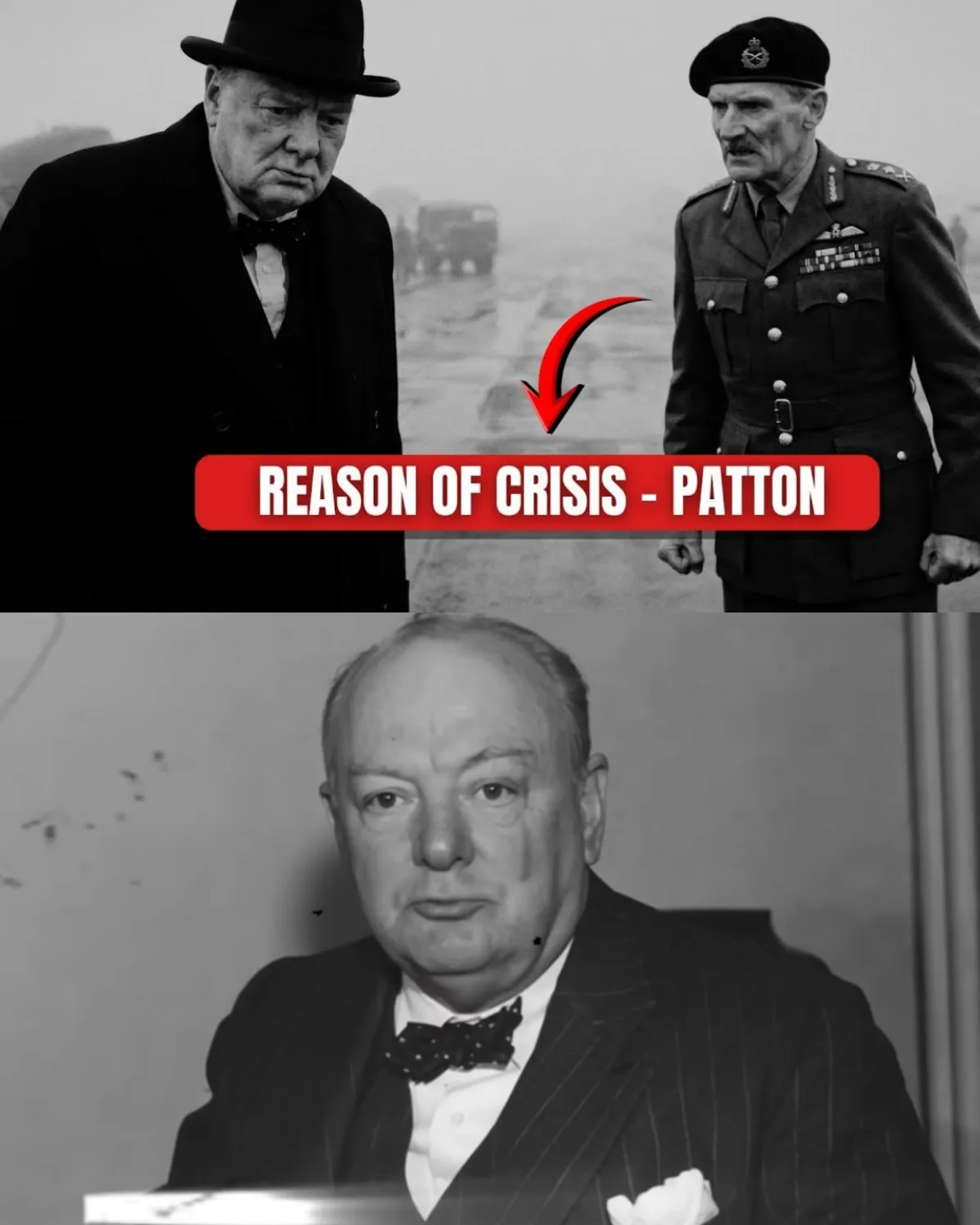

“Pride Doesn’t Win Wars”: How Churchill Shut Down Montgomery’s Demand to Fire Patton

On the morning of March 23, 1945, Winston Churchill sat aboard his command aircraft, preparing to land in Germany. He was minutes away from witnessing what he believed would be a defining moment of British military prestige: Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s Operation Plunder, the meticulously planned crossing of the Rhine River.

Churchill had invested heavily in this moment—politically, emotionally, and symbolically. The operation was meant to show the world that Britain still set the standard for modern warfare. Months of preparation, thousands of guns, airborne drops, and a carefully staged media spectacle were all in place.

Then the radio crackled.

“Patton crossed last night.”

Not today. Not as part of Montgomery’s grand operation. But the night before—quietly, quickly, and without permission.

In that instant, Churchill understood the magnitude of what had just happened. The Rhine was Hitler’s last great natural barrier in the west, and George S. Patton had crossed it with little more than assault boats, speed, and audacity.

Before Churchill’s plane touched down, Montgomery had already sent his demand.

Patton must be relieved of command immediately.

What Montgomery Had Been Promised

To understand Montgomery’s fury, one must understand what Churchill had promised him.

Back in January 1945, Churchill personally assured Montgomery that Operation Plunder would be the centerpiece of Allied victory in Europe. It would be British-led, British-planned, and unmistakably British in style—methodical, overwhelming, and precise.

Montgomery spent two months assembling one of the largest river-crossing forces in history: over a million men, tens of thousands of vehicles, thousands of artillery pieces, and massive airborne support. War correspondents were invited. Photographers were positioned. Churchill had even drafted the celebratory communiqué in advance.

Everything was ready.

Except Patton refused to wait.

Patton’s Midnight Gamble

On the night of March 22, Patton called Dwight D. Eisenhower from Luxembourg.

“Ike, quick update. Third Army crossed the Rhine at Oppenheim. Minimal casualties.”

Eisenhower immediately grasped the political disaster unfolding.

“George,” he asked carefully, “did you coordinate this with Montgomery?”

Patton’s reply was classic Patton.

“Monty’s got his crossing tomorrow. Didn’t want to bother him with details.”

Within minutes, Eisenhower was scrambling to contain what he later called the biggest diplomatic crisis of the war.

Montgomery’s Cold Fury

By dawn, Montgomery had confirmation that American forces had crossed the Rhine twelve hours before his operation was scheduled to begin.

Witnesses described his reaction not as rage, but ice.

“This is strategic insubordination,” Montgomery declared. “I want Patton relieved, court-martialed, and sent home.”

His staff tried to soften the blow. The crossing had succeeded. The bridgehead was expanding. Casualties were light.

Montgomery dismissed it all.

“Success is irrelevant,” he said. “Discipline is paramount.”

He drafted a formal demand to Churchill, insisting that Patton’s removal was necessary to preserve Allied command authority.

Churchill’s Impossible Choice

Churchill received Montgomery’s message minutes before landing. He read it three times.

Patton had crossed the Rhine first. Montgomery’s grand operation was now overshadowed before it even began.

Support Montgomery, and Churchill would be demanding the firing of America’s most aggressive general for winning too quickly.

Support Patton, and Churchill would be undermining British military prestige in full view of the world.

When Churchill descended the aircraft steps, Montgomery was waiting, rigid and formal.

“Prime Minister,” Montgomery said, “I must insist Patton be relieved. His insubordination cannot stand.”

Churchill raised a hand.

“Bernard,” he said quietly, “answer me one question honestly. If Patton had asked permission to cross last night, what would you have said?”

Montgomery didn’t hesitate.

“I would have denied it.”

The Sentence That Ended the Argument

Churchill paused, then asked the question Montgomery did not expect.

“Is this about strategy—or pride?”

Montgomery replied stiffly that it was about command discipline.

Churchill’s response was devastating.

“It’s about Patton making you look slow.”

The words hung in the cold German air.

Churchill continued, calmly dismantling the illusion both men had lived with for years. British doctrine—careful preparation, overwhelming force—had saved lives. But Patton had just crossed the same river in one night with a fraction of the resources.

“The war is ending,” Churchill said. “Every day we delay, the Soviets advance further west. Patton understands this.”

Montgomery asked the question that revealed everything.

“So you’re choosing him over me?”

Churchill shook his head.

“I’m choosing to end the war before Europe belongs entirely to Stalin.”

Why Churchill Refused to Fire Patton

Montgomery made one final appeal. If Patton went unpunished, command authority meant nothing.

Churchill agreed—then explained why it didn’t matter.

“If I demand Eisenhower fire Patton,” Churchill said, “the Americans will ask why. And I’ll have to explain that we’re firing their most successful general because he succeeded too quickly without British permission.”

He reminded Montgomery of a truth few wanted to say aloud.

The Americans supplied the majority of men, matériel, and casualties. They funded the war. And their general had just demonstrated an operational speed Britain could no longer match.

“To do this,” Churchill concluded, “would be to admit that British pride matters more than Allied victory.”

The Message to Eisenhower

After leaving Montgomery, Churchill returned to his aircraft and dictated a message to Eisenhower.

He declined to support Montgomery’s request.

Patton’s operation, while uncoordinated, had succeeded and advanced Allied objectives. No action should be taken.

Then Churchill added a handwritten note:

“Ike—keep Patton moving. We can’t match his speed, but we can’t afford to lose it.”

Churchill’s Private Admission

That evening, Churchill met privately with his physician, Lord Moran. Away from generals and politicians, the prime minister spoke with brutal honesty.

“I’ve just chosen American results over British pride,” Churchill said. “And Montgomery will never forgive me.”

Then came the deeper truth.

“We are no longer the leading military power in this alliance,” he admitted. “We haven’t been for some time. I’ve just been too proud to say it.”

When Moran asked if he regretted the decision, Churchill answered instantly.

“Not for a second. Pride doesn’t win wars. Speed does.”

A Moment That Redefined the Alliance

Montgomery never forgave Churchill. British military leadership protested formally. Churchill brushed it aside.

The signal was clear: operational success mattered more than protocol.

Patton understood immediately. In his diary, he wrote that the British finally realized the war would be finished the American way.

Years later, in his memoirs, Churchill acknowledged the truth publicly. Montgomery’s Operation Plunder was masterfully planned—but Patton’s improvised crossing achieved the same result faster and with fewer resources.

It was uncomfortable. It was undeniable.

When Montgomery demanded Patton be fired, Churchill did something far more consequential.

He admitted that the future of warfare had arrived—and Britain was no longer leading it.