Shadows the Army Would Not Unleash: The Apache Warriors America Feared to Fully Send to War

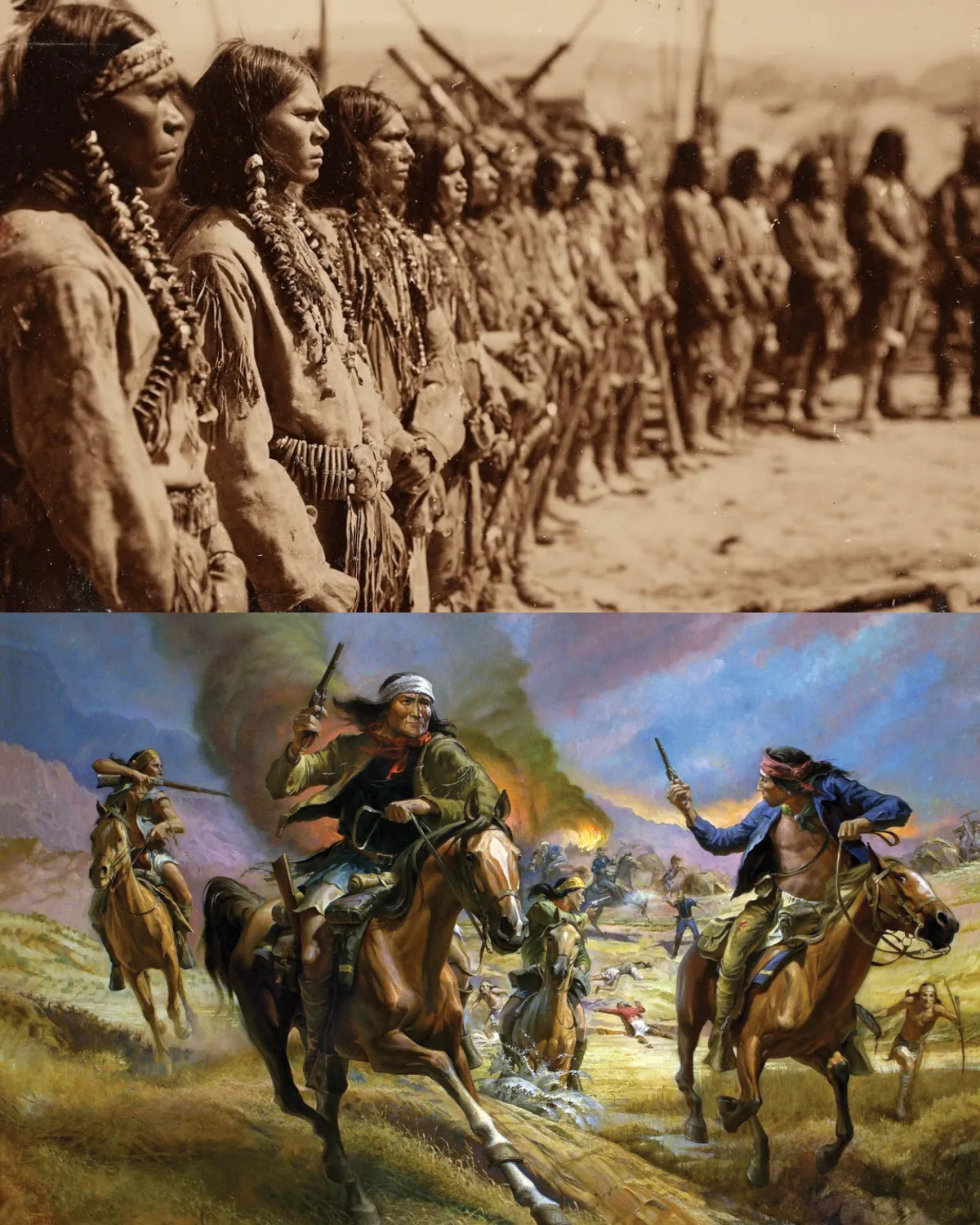

History often remembers its wars through photographs of landings, parades of medals, and the names of generals carved into stone. What it forgets—sometimes deliberately—are the men whose skills were too effective, too unsettling, too incompatible with the narratives nations prefer to tell about themselves. During the Second World War, the United States quietly recruited some of the most capable warriors it had ever encountered: Apache men whose ancestors had resisted the American Army longer than any other Indigenous nation. And then, after recognizing exactly what they could do, the military made a decision that would shape their service forever.

They would be used—but never unleashed.

A Debate Behind Closed Doors

In the spring of 1942, while American newspapers focused on shipbuilding quotas and Pacific island maps, a different conversation unfolded inside the War Department in Washington, D.C. Major General Thomas Bingham sat across from Colonel James Harrison, both men staring at a stack of personnel files unlike any the Army had seen before.

The files belonged to Apache volunteers.

Their aptitude scores were extraordinary. Physical endurance well beyond infantry standards. Tracking abilities that bordered on the unbelievable. Psychological assessments that revealed patience, emotional restraint, and spatial awareness unmatched by even elite Ranger candidates.

But it wasn’t the numbers that disturbed the generals.

It was the history.

These men were descendants of warriors who had fought the United States Army itself for decades—fighters who had survived pursuit by thousands of cavalrymen, who had turned deserts and mountains into weapons, who had understood guerrilla warfare long before the term existed. The bloodlines of Cochise, Victorio, and Geronimo ran through these recruits. The Army had defeated their ancestors not through superior tactics, but through starvation, imprisonment, and relentless numbers.

Now their grandsons were volunteering to fight for the same nation.

And that frightened the people in charge.

What the Training Revealed

At Fort Huachuca, Arizona, a controlled training exercise was scheduled to test a group of twelve Apache recruits. Their task was simple on paper: infiltrate a defended perimeter manned by two full infantry companies—nearly 200 soldiers—equipped with alarms, patrol rotations, and modern detection protocols.

The exercise was expected to last three days.

It ended in eleven hours.

Every checkpoint was bypassed. Every sentry neutralized without alarms. Dummy explosives were placed on command tents, fuel depots, and communications centers. When the exercise was halted, the commanding officer of the defending force was found asleep in his tent, a training knife laid beside his head.

He never heard them enter.

He later requested an immediate transfer, stating privately that he had never felt such primal fear—not in France, not under artillery fire, not during the Great War.

The message was unmistakable.

If twelve Apache soldiers could dismantle two companies in a controlled environment, what could they do on a real battlefield?

And more dangerously—what could they do if ever turned against American forces?

William Naiche and the Burden of Legacy

Staff Sergeant William Naiche was twenty-six years old, raised on the Mescalero Apache Reservation in New Mexico. He spoke four languages fluently. He could run fifty miles through broken terrain in a single day. He could remain motionless for sixteen hours without fatigue. He understood desert survival not as training, but as inheritance.

His grandfather had ridden with Geronimo.

When Pearl Harbor was attacked, Naiche walked thirty miles to the nearest recruitment station. He did not do it out of blind patriotism. The government had imprisoned his family, taken Apache land, attempted to erase Apache culture through forced assimilation.

But Naiche understood something Washington did not.

The Apache way of survival had always been adaptation. And in the modern world, proving worth required stepping into its wars.

Too Effective for Doctrine

Attempts to integrate Apache soldiers into standard infantry units failed—not because they underperformed, but because they disrupted doctrine itself. During training exercises at Fort Benning, Naiche’s unit was ordered to conduct a textbook assault on a fortified position.

Naiche disagreed silently.

Before the exercise began, he identified weak points in the enemy perimeter simply by observation. When the assault started, his squad vanished. They reappeared behind enemy lines, destroyed the ammunition depot, and collapsed the defensive position from within.

The training cadre was furious.

This wasn’t how wars were supposed to be fought.

A senior sergeant told Naiche bluntly: “You think like a guerrilla, not like a soldier. And guerrillas win wars—but not the kind armies want to admit.”

Naiche understood. The Apache way of war wasn’t about holding ground. It was about making the enemy afraid to move, afraid to sleep, afraid to exist.

That kind of power made generals nervous.

The Decision That Changed Everything

In Washington, the argument reached its conclusion. Colonel Harrison pushed for an elite Apache combat unit—unconventional warfare specialists for the Pacific. General Bingham refused.

What would happen after the war, he asked, when these men returned home with advanced combat training? What if resentment turned into resistance? What if the next Geronimo wasn’t armed with a rifle, but with demolitions expertise and modern tactics?

The compromise was quiet and devastating.

Apache soldiers would be used as scouts, trackers, and reconnaissance specialists—never concentrated, never autonomous, never given command. Their value would be extracted. Their independence contained.

Lieutenant Robert Chen, who had championed the program, was reassigned.

The Apache would serve in the shadows.

Ghosts in the Pacific

In Guadalcanal, New Guinea, Bougainville, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa, Apache scouts became invisible foundations of American success. They detected ambushes no one else could see. They tracked enemy officers through jungle that swallowed entire battalions. They operated alone, without radio contact, living off the land.

One Apache scout prevented a massacre by noticing bird calls that were wrong for the time of day.

Another tracked a Japanese commander forty miles through jungle based on disturbances no map could capture.

Their names rarely appeared in reports.

But soldiers remembered.

A Mission That Changed a Battle

On Bougainville Island, Colonel Sam Griffith quietly authorized a reconnaissance mission that never officially existed. Naiche went ashore alone three days before the assault. No support. No extraction backup.

For seventy-two hours, he mapped machine gun nests, bunkers, command posts. He killed only when necessary, understanding the weight of every life taken. He discovered a hidden valley—rigged with buried artillery shells and interlocking fire—that would have annihilated an American flanking force.

He returned with minutes to spare.

The battle plan was rewritten.

Hundreds lived.

Naiche received no medal.

After the War

Apache soldiers returned home to unchanged reservations. Poverty. Neglect. Silence. They had proven their worth in combat, yet remained second-class citizens in peace.

Naiche spent the rest of his life as a ranchhand. He rarely spoke of the war. When asked why he fought, he answered simply:

“Because fighting is how we proved we could not be erased.”

The Legacy in the Shadows

In the National Museum of the American Indian, there is a small display: a map, a compass, a knife. The placard does not explain why these men were feared by their own commanders. It does not ask why excellence frightened authority.

But the map still bears pencil marks—quiet evidence of a war fought unseen.

The Apache warriors of World War II were not kept from the front because they lacked courage.

They were kept back because they had too much of it.

And history is only now beginning to understand what it lost by never fully trusting the shadows.