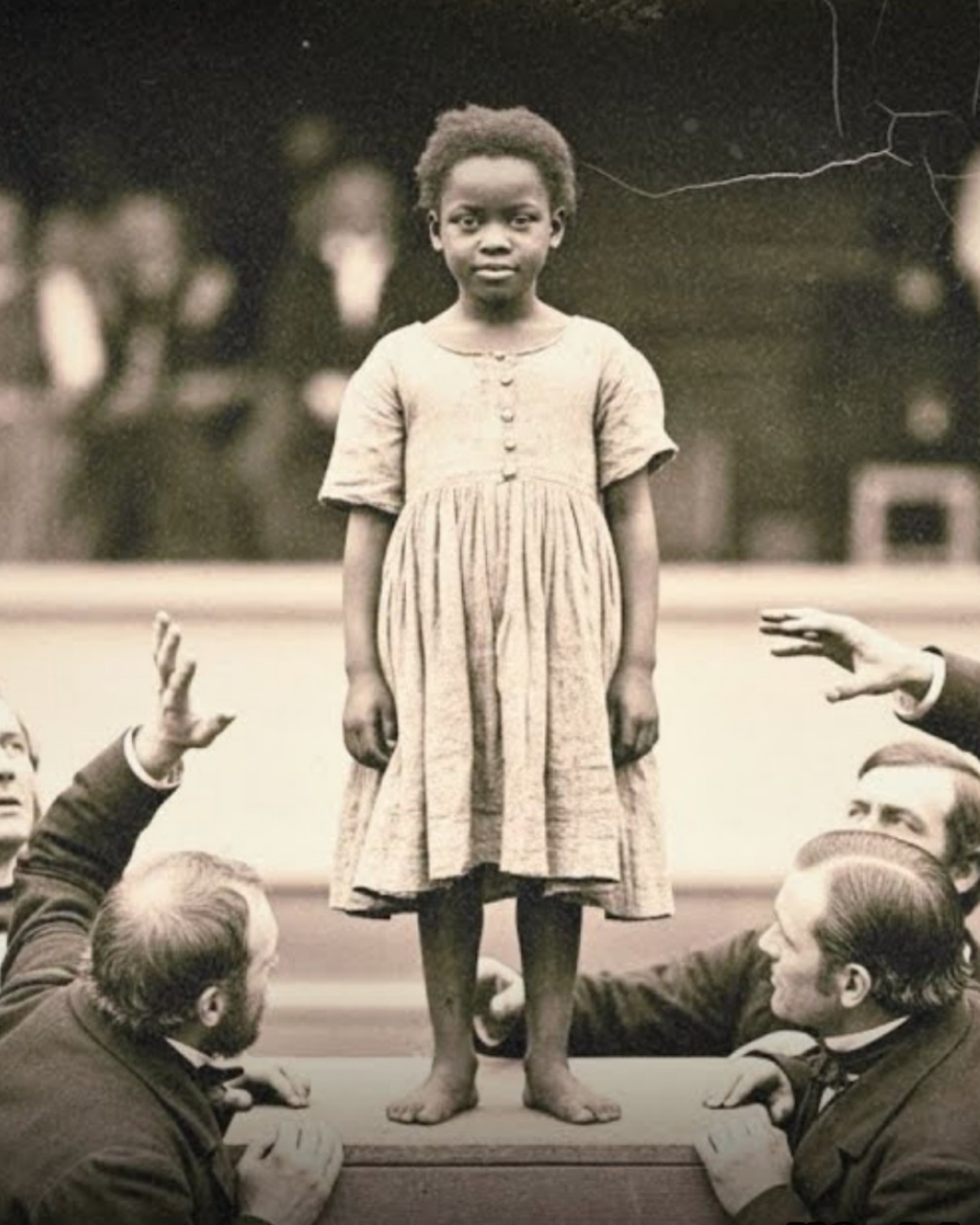

She Was Posed as a Slave—But the Photograph Hid Proof She Was Her Enslaver’s Daughter

On a cold Tuesday morning in March 2024, a small anonymous package arrived at the National Archives.

It did not look extraordinary. No return address. No sender name. Just brown paper, careful handwriting, and a single typed note slipped inside.

Some things are not what they appear. The truth matters more than my name.

Dr. Sarah Mitchell, curator of the Civil War Photographic Collection, had spent twelve years receiving donations like this—daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, cartes de visite, all fragments of America’s most violent century. But something about this package made her pause before opening it. Experience had taught her that the most dangerous truths often arrived quietly.

Inside was a small carte de visite, a popular photographic format during the Civil War era. The image appeared familiar, even predictable: a white woman in an elegant silk dress standing beside a younger Black woman dressed plainly, her posture deferential, her eyes lowered.

On the back, a handwritten caption read:

Caroline Ashford and her girl Rachel. Charleston, South Carolina. March 1863.

At first glance, it was textbook propaganda—an image meant to portray slavery as benign, orderly, even benevolent. Dr. Mitchell had catalogued dozens like it. But the donor’s warning lingered in her mind.

Examine it carefully.

Under magnification, something felt wrong.

Not emotionally—professionally.

Dr. Mitchell called in a colleague, forensic photo analyst Dr. James Warren, and together they scanned the photograph at extreme resolution. As facial mapping software overlaid measurements, the room grew silent.

The women’s faces aligned.

Not loosely. Not coincidentally. But with precision.

Interocular distance. Jaw angle. Cheekbone structure. Ear placement. Genetic markers embedded in bone.

“These two women,” Warren said quietly, “are closely related.”

Sisters.

Or worse.

The implication hit immediately. If Rachel and Caroline shared a father, then that father—a wealthy Charleston plantation owner—had raped an enslaved woman and enslaved his own child.

And the photograph? It wasn’t a record of kindness.

It was evidence of a crime.

The Ashford family records filled in the next layer. Caroline Ashford, born in 1834, was the legitimate daughter of Robert Ashford, owner of Ashford Grove Plantation. Her mother was white. Her education elite. Her marriage advantageous—until her husband died fighting for the Confederacy.

Rachel, meanwhile, appeared in plantation inventories as “female child, age three,” daughter of an enslaved woman named Sarah. She was assigned to domestic work. Kept in the house. Hidden from visitors.

One chilling margin note in an 1855 ledger read:

Girl looks like family. Keep her in house. Away from visitors.

They knew.

They had always known.

But the most devastating discovery was still waiting.

When Dr. Mitchell scanned the photograph at maximum resolution, she noticed Rachel’s hands. They were clasped—but not empty. Hidden between her palms was a small folded square of paper.

Rachel had concealed something during the photograph session.

And she had done it deliberately.

Days later, the anonymous donor resurfaced via encrypted email. They had purchased a box of Ashford family materials at a Charleston estate sale in 1994 and waited three decades to come forward—until the last living Ashford descendant died.

They arranged a handoff at the Charleston Archives and History Center.

Inside the box was a diary, letters, a family Bible—and the folded paper Rachel had hidden in her hands.

Dr. Mitchell unfolded it carefully.

It was a confession.

Written and signed by Robert Ashford himself.

I, Robert Ashford, do hereby acknowledge that Rachel, daughter of Sarah, is my natural daughter, born of my body, and is kin by blood to my legitimate daughter, Caroline.

God forgive me for the evil I have done.

The date: April 7, 1863.

Robert Ashford had raped an enslaved woman. Fathered a child. Enslaved her. Then—dying—gave his daughter proof of the truth, while refusing to free her publicly.

Rachel had hidden that confession in a photograph meant to erase her humanity.

A silent rebellion.

Further documents confirmed everything. Caroline’s diary admitted the truth. Letters revealed her shame—and her refusal to act. The family Bible contained one final entry, written by Rachel herself after emancipation:

I add my name because I am family, whether acknowledged or not.

Rachel walked away in 1865, carrying the confession with her. She rebuilt her life in Philadelphia, became a teacher, raised children, and died free—having written herself back into history.

DNA testing later confirmed what the photograph had whispered for over a century: Rachel and Caroline were half-sisters.

The image now hangs in a permanent exhibit titled Hidden in Plain Sight, no longer as propaganda, but as testimony.

A portrait once meant to lie now tells the truth.

Not because the powerful confessed—but because the enslaved refused to disappear.