She Was the Joke of a Frontier Town—Until She Stepped Between a Whip and a Stranger, and Everything Fort Laramie Thought It Knew About Power, Shame, and Courage Began to Rot

PART 1

Nobody remembers the quiet mornings. History doesn’t bother with them.

It skips straight to the crack of the whip.

But that Friday in Fort Laramie didn’t start with violence. It started the way most days did—dust floating lazy in the air, sunlight too sharp for comfort, and people pretending they didn’t see one another unless it was useful.

Martha Wyn was sweeping.

She always swept first. Same boards. Same rhythm. Same patch of stubborn dirt in front of her father’s dry goods store that never seemed to stay clean no matter how many passes she made with the broom. She knew the pattern by heart. Three strokes forward, one back. Don’t rush. Don’t look up. Don’t invite commentary.

It wasn’t humility. It was survival.

The boardwalk creaked somewhere behind her. Boots. More than one pair. Men, by the sound of it—heavy, careless steps that didn’t bother apologizing to the wood. Martha’s shoulders tightened, just a little. She kept sweeping.

“Make way for the mountain.”

The voice carried. High. Bright. Enjoying itself.

Laughter followed, like it always did.

Martha felt it anyway—the heat rising in her face, the familiar burn crawling up her neck. Her hands tightened around the broom handle until the wood pressed into her palms. She didn’t look up. Looking up only made it worse. Looking up made you available.

“Careful,” the same voice went on. “She blocks the whole street if she turns sideways.”

More laughter. Someone snorted. Someone else added something she couldn’t quite hear but didn’t need to.

Cal Sterling never missed an audience.

He liked people to know when he’d entered a space. The mayor’s son had a talent for it—how to bend attention around himself, how to make cruelty sound like sport. He stood somewhere to her left now, she could tell, close enough that the smell of tobacco and expensive soap crept into her awareness.

“You’re going to wear a hole clean through those boards, girl.”

Martha didn’t respond.

Behind her, the shop door opened.

“Martha.” Her father’s voice. Not sharp. Not kind either. Just… tired. “Leave it. We’ve got inventory.”

She nodded, grateful for the excuse, and stepped inside without a word.

The shop was cool and dim, the air thick with familiar smells—leather, coffee beans, lamp oil, dust that had soaked into wood over decades. It was small. Modest. But it was orderly. That mattered to her. Order meant things stayed where you left them. Order meant fewer surprises.

Thomas Wyn moved behind the counter, adjusting his ledger like he needed something solid to hold on to. He didn’t look at her right away.

“You all right?” he asked finally.

“I’m fine,” Martha said, because that was what daughters like her were supposed to say.

He studied her a moment, eyes softening, then looked away again. He hadn’t defended her in years. Not because he didn’t love her—she knew better than that—but because defending her only sharpened the knives. Fort Laramie loved blood in the water.

The morning passed in pieces. Mrs. Chen came in for flour and sugar, counting out coins so worn the faces were nearly gone. Old Peter lingered too long, complaining about his knees, his back, the weather, everything but the loneliness that sat behind his words. A freight driver bought rope and nails, barely registering Martha’s existence beyond the transaction.

Invisible had its uses.

She was restocking ribbons—black ones mostly, the kind people bought for funerals—when the door opened again.

This time, the air changed.

Martha didn’t know how else to describe it. No sound announced him. No boot scrape, no cough. Just… pressure. Like a storm settling in.

She turned.

The man filled the doorway.

He was tall. Not just taller than her—taller than anyone she’d seen in Fort Laramie. Broad shoulders wrapped in patchwork fur, dark and worn, stitched from animals she could name and some she couldn’t. The smell of pine smoke and cold air clung to him, sharp and clean, like he didn’t belong indoors at all.

His face was hard in a way that didn’t come from cruelty. More like weather had carved it. His eyes—those were what stopped her. Pale. Almost colorless. The flat gray of winter ice, the kind that didn’t reflect much back at you.

A mountain man. A real one.

Not the half-drunk trappers who stumbled into town twice a year, loud and desperate and looking to trade pelts for whiskey. This man felt older than that. Quieter. Like he belonged to places where people didn’t talk much because there wasn’t anyone around to hear.

Thomas Wyn went very still behind the counter. His hand drifted, almost without him noticing, toward the rifle kept beneath the register.

“Need supplies?” the stranger asked.

His voice was low, rough, like it didn’t get used often.

Thomas cleared his throat. “We—uh—we’ve got most things. Depends what you’re after.”

“Coffee. Salt. Flour. Dried beef.” A pause. “Ammunition, if you carry it.”

“We do,” Thomas said, then hesitated, glancing at Martha. “Martha. Get the man his goods.”

She moved, aware of his eyes following her across the store. Not leering. She knew leering. This wasn’t that. This was assessment. The way you looked at a tool to see if it would hold up.

It unsettled her more than mockery ever had.

She gathered the items carefully, stacking them the way she always did. Her hands were steady. She took pride in that. The stranger waited without shifting his weight, without filling the space with noise. The store felt smaller with him in it.

“You’ve got scales that work?” he asked suddenly.

“Yes, sir.” She met his gaze without thinking. “We keep them honest.”

Something flickered across his face. Not quite a smile. “Good.”

She weighed everything, showed him the numbers. He nodded once. When she reached for brown paper to wrap the goods, he lifted a hand.

“Just load it. I’ve got saddlebags.”

They worked in a strange, quiet rhythm. Martha packing. The stranger watching. Her father hovering uselessly, nervous energy with nowhere to go.

When she finished, the man counted out payment—gold coins. Real ones. More than enough.

“That’s too much,” she said before she could stop herself.

His gaze sharpened. Focused fully on her for the first time.

“Scales are honest,” he said. “So’s the weight. You earned it.”

Heat climbed her neck again, but this time it wasn’t shame. It was something warmer. More dangerous.

“I can help you carry it,” she offered.

“I’ve got it.”

He gathered the bundles like they weighed nothing, tipped his hat to Thomas, and turned toward the door.

Panic flared in her chest—sudden and irrational. The sense that something important was about to leave and never come back.

“Sir.”

The word escaped her before she could think better of it.

He paused.

Martha swallowed. “People here,” she said quietly. “They’ll try to make trouble for you. Just because you’re different. Just because they can.”

The corner of his mouth lifted a fraction. “I know.”

“It’s not right,” she added, because once she started, she couldn’t stop. “What they do.”

He studied her a long moment, eyes unreadable. Then, softly: “You carry a lot.”

She froze.

“It’s not all yours,” he said.

And then he was gone.

The door swung shut behind him, and Martha stood there with her heart racing, her hands trembling, and no idea why six simple words felt like they’d cracked her open.

“You’re staring,” her father muttered, scooping up the coins. “Strange fellow. Too much gold for a drifter.”

“He didn’t steal it,” Martha said.

Thomas shot her a look. She didn’t back down.

An hour later, shouting erupted outside.

Martha dropped the ribbon spool and ran.

A crowd had gathered in the square. Always bad news. Fort Laramie didn’t gather unless it smelled blood.

Her stomach dropped when she saw him.

The mountain man stood beside his horse, supplies half-loaded, posture relaxed in a way that made everything else feel tense by comparison. Facing him were Mayor Sterling and Sheriff Cutler, deputies flanking them with rifles already raised.

“Answer when spoken to,” Cutler barked.

“Didn’t take anything that wasn’t sold fair,” the stranger said evenly. “Receipts if you want them.”

“Receipts,” the mayor spat. “The army payroll wagon was hit three days ago. Fifteen hundred dollars gone. And here you come, pockets full of gold.”

Martha’s chest tightened. She’d heard the rumors. Everyone had. Rumors were Fort Laramie’s favorite food.

They searched him. Roughly. His saddlebags. His bedroll. Found nothing but what she’d sold him.

“Then he hid it,” Sterling snapped. “Or buried it.”

“I wasn’t near your wagon,” the stranger said flatly.

The mayor’s face hardened. “Tie him up.”

Twenty lashes, he ordered. Public square.

The word public rippled through the crowd like anticipation.

Martha stepped forward without thinking. “You can’t. You don’t have proof.”

Her father’s hand clamped on her arm. “Don’t.”

Cal Sterling appeared beside his father, grinning. “Look at that. The fat girl’s got opinions.”

Laughter broke out again.

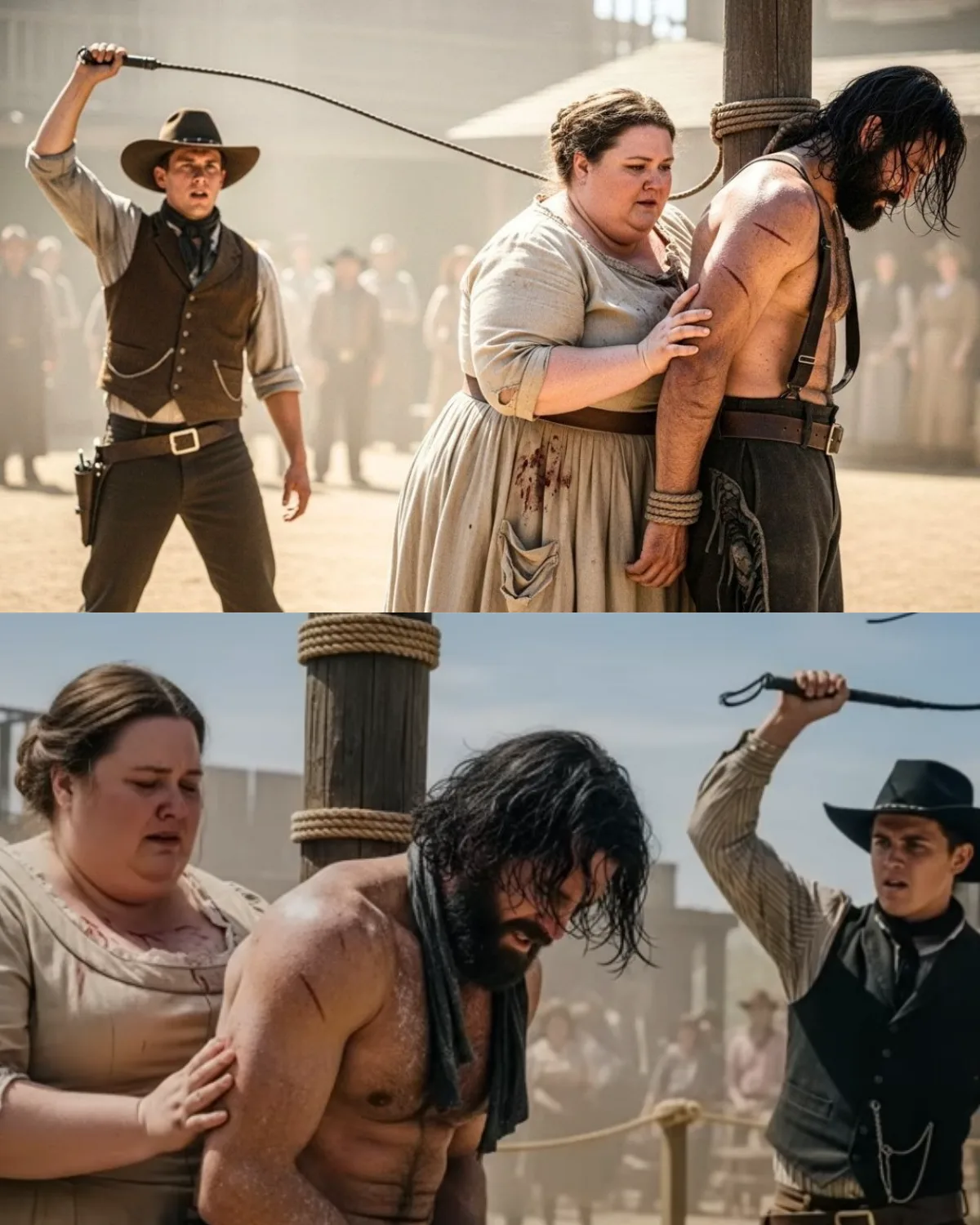

They dragged the stranger to the post. Ripped his coat. His shirt. Martha saw scars—old ones—crossing his back like a map of survival.

Cal took the whip.

The first lash cracked. Then another. Then another.

The stranger didn’t make a sound.

By the tenth, blood ran freely. The crowd leaned in.

“Finish it,” the mayor said.

Cal wound up.

And Martha moved.

She didn’t think about consequences. Or fear. Or how small she was.

She threw herself forward and pressed her body against the stranger’s back.

“No.”

The whip fell.

Pain exploded across her shoulders—white-hot, blinding. She screamed. The world tilted. She tasted dust and copper.

Silence followed.

For the first time in years, Fort Laramie remembered what shame felt like.

And that was when the mountain man broke his chains.

PART 2

They told the story wrong afterward.

Stories always get bent when fear’s involved. People rounded the edges, softened the shame, sharpened the parts that made them feel less complicit. By the next morning, depending on who you asked, Martha Wyn had either fainted at the whipping post, been pushed by accident, or acted out of some foolish, womanly impulse that no one should take seriously.

Nobody wanted to say what really happened.

That she chose.

That she stepped forward when every sensible instinct screamed stay still.

That the sound she made when the lash hit her back wasn’t weakness—it was defiance tearing its way into the open.

They carried her to Doc Morrison’s office because there was nowhere else to put her. Because no one quite knew what to do with a woman who’d cracked the town’s reflection and forced them to look at it.

The mountain man carried her most of the way.

He moved through the stunned crowd like weather—slow, inevitable, unstoppable. Blood ran down his arms and chest, dark against his skin, but his grip on her was careful, almost reverent. As if she were something fragile and holy both at once.

No one tried to stop him.

Not the sheriff.

Not the deputies.

Not the mayor.

Cal Sterling stood frozen in the square, whip hanging useless at his side, his grin gone, replaced by something thin and panicked that didn’t know how to perform without an audience cheering it on.

Inside the doctor’s office, everything smelled like antiseptic and fear.

Doc Morrison swore when he saw Martha’s back.

“Jesus Christ,” he muttered—not loud, not theatrical. Just tired. “Lay her down. Easy. Easy.”

The mountain man lowered her onto the examination table as if setting down something priceless. He stayed close while the doctor cut away fabric and cleaned the wound, his jaw tight, his eyes tracking every movement like he was memorizing it.

“She’ll live,” Morrison said finally. “But that cut’s deep.”

“I’ll pay,” the stranger said. “Whatever it costs.”

Martha stirred, breath hitching. “They’ll come for you,” she whispered, the words slurred. “They won’t stop.”

He brushed his knuckles along her cheek, a touch so gentle it barely registered. “They won’t catch me.”

“You can’t stay.”

“I’m not staying,” he said. “I’m returning.”

Her eyes fluttered open just long enough to catch his meaning—and then he was gone, slipping out the back like smoke through a crack in the wall.

By nightfall, Fort Laramie was arguing with itself.

Some said the mountain man had broken chains like rotten twine. Others said the shackles had been faulty. A few swore they heard gunshots in the hills afterward, though no one could say where.

Mayor Sterling stood on the steps of the jail and declared the fugitive a savage criminal who’d assaulted lawful authority. He announced a manhunt. He promised justice.

The crowd clapped because that’s what crowds did.

But the sound didn’t land the way it used to.

Martha drifted in and out of pain for three days.

The wound burned like it had a mind of its own, a living thing carved into her back. Doc Morrison changed the bandages twice daily, muttering under his breath about stupidity and courage being two sides of the same damned coin.

Her father came once.

He stood in the doorway like he didn’t know how to cross the threshold anymore. He asked if she needed anything. She said no. He nodded and left, and neither of them said what mattered.

On the fourth night, the bells rang.

Fire bells. Not frantic yet, but wrong enough to jolt her upright despite the pain. Morrison cursed and ran for the door.

From the window, Martha saw orange light bloom against the dark.

Mayor Sterling’s private warehouse burned clean and fast.

No one died. Someone had been careful about that. But by morning, the place was ash and twisted iron, and everyone knew exactly whose property had gone up in smoke.

Cal Sterling paced the ruins, shouting that the savage was watching, laughing, marking them.

Two nights later, the supply depot burned.

Then the lumber yard.

Then the feed store where the mayor’s brother-in-law kept books that never quite balanced.

Fort Laramie learned what it felt like to be hunted by silence.

Sheriff Cutler organized patrols—four men at a time, rifles loaded, nerves frayed. They talked big in daylight and jumped at shadows after dark. No one ever saw anything. Just fire, always precise. Always selective.

Martha healed slowly.

By the end of the second week, she could sit up. Walk a few steps. Breathe without biting down on pain. When she returned to the square for the first time, people stared like she’d become something else entirely.

Not invisible anymore.

Cal Sterling intercepted her halfway across.

He smelled like whiskey and desperation.

“You cost me,” he hissed, grabbing her arm. “Every fire. Every shipment. That’s on you.”

Mrs. Chen appeared beside them, cleaver in hand, calm as a lake before a storm.

“Let go,” she said.

Cal laughed, ugly and brittle, and released Martha. “Tell your savage we’re bringing in professionals.”

Martha’s arm throbbed long after.

That night, the mountain man came to her porch.

“You shouldn’t be out here,” he said quietly.

“You shouldn’t either.”

They spoke in whispers, close enough that she could smell smoke and pine and something sharper beneath. He checked her wound with careful eyes.

“They’re bringing hunters,” she warned.

“I know.”

“Then leave.”

“No.”

The word was final.

He told her his name before he left.

Ronan Cade.

The next morning, one of the hired hunters was found dead in his bedroll. Throat cut so clean it barely bled.

The other three packed up and fled before noon.

Fear changed hands that day.

Sheriff Cutler came calling soon after.

“You seen him?” he asked, hat in hand, voice rough.

“No,” Martha said, and it was mostly true.

The sheriff lingered, then left, carrying more doubt than certainty.

That night, Martha made a decision she couldn’t unmake.

She slipped out past midnight, moving through shadows, following instinct more than plan. The burned warehouse district smelled like old smoke and consequences.

“This is a good way to get shot,” Ronan said from the darkness.

They argued in whispers. About revenge. About justice. About what came after fire.

“You kill Sterling and leave,” Martha said, “someone worse takes his place.”

He didn’t answer right away.

Then lantern light spilled across the ruins and they dove for cover together, Ronan’s hand steady on her shoulder, holding her still while deputies passed within feet.

Afterward, he gave her a place to find him if she ever needed to.

“Only if you’re in danger,” he said.

She nodded.

She didn’t promise.

The cage went up two days later.

Iron bars welded into something too small to stand in, planted right in the square like a warning carved in metal.

They put Mrs. Chen inside.

“Aiding a fugitive,” Mayor Sterling announced. “She stays until he turns himself in.”

Martha felt something inside her break—not bend, not crack. Break.

She called them cowards.

Sterling ordered her arrested.

And Ronan Cade appeared on the roof with a rifle and a promise of fire.

“Let them go,” he said. “Or I start shooting.”

Sterling backed down.

The town watched him do it.

That mattered more than anyone realized yet.

Martha stayed.

When her father said they should leave, she said no.

“This town changes,” she told him. “Or it burns. Either way, I’m not running.”

Thomas Wyn looked at his daughter like he was seeing her for the first time since his wife died. Then he nodded.

They began quietly.

Women stood together. Doc Morrison stopped being discreet. Old Peter talked too loud in the saloon. Martha taught children—and then adults—to read.

The mayor responded with curfews. New deputies. Outside men.

Pressure built.

And pressure, Martha had learned, either made things stronger—or made them explode.

She walked to the foothills one afternoon with her mother’s derringer heavy in her pocket.

Ronan met her at the line shack.

“You shouldn’t have come,” he said.

“I know.”

They argued again. Louder this time. About bait. About plans. About whether Fort Laramie could actually change.

“We make him overreach,” Martha said. “Make him show everyone who he really is.”

“You’ll get killed.”

“Then help me not die stupid.”

Silence stretched between them, taut as wire.

Finally, Ronan nodded.

They planned until dusk.

When she left, he kissed her like he was afraid he wouldn’t get another chance.

She almost missed Cal Sterling waiting on the path home.

He took her at gunpoint.

Paraded her through town.

Put her in the cage.

The screaming started hours later.

Fire, real fire this time.

Ronan came through the jail door like a storm given shape, shot the lock, hauled her free while smoke rolled low and thick.

Cal Sterling tried to stop them.

Martha shot him.

The mayor arrived with guns and fury and authority in his voice—and Doc Morrison arrived with proof.

Books. Records. Names.

Then the town arrived.

Lanterns. Torches. People who’d finally decided silence cost more than speaking.

Mayor Sterling lunged.

Sheriff Cutler shot him in the leg.

And just like that, the fight went out of Fort Laramie.

They locked the Sterlings in real cells.

Cutler resigned.

By dawn, the town felt… different.

Not healed. Not safe.

But awake.

Martha sat on the jail steps as the sun came up, Ronan beside her, rifle across his knees.

“What happens now?” she asked.

“Now,” he said, “we see if the truth holds.”

He hesitated. “And then I leave.”

Her chest tightened.

He looked at her then. “Come with me.”

She didn’t answer right away.

PART 3

The thing about towns like Fort Laramie—places built fast and crooked and proud of it—is that they don’t collapse all at once.

They creak first.

They groan.

They pretend nothing’s wrong while the rot works its way through the beams.

Morning came gray and slow after the fire. Smoke still hung low, clinging to clothes and hair and the backs of throats. People stepped outside cautiously, as if the town itself might lash out if startled.

Mayor Sterling lay on a cot in the jail, pale and silent, his leg bound tight. Cal was two cells over, shoulder bandaged, eyes hollow. For the first time in his life, no one laughed at his jokes. No one even looked at him unless they had to.

That alone would’ve broken him, Martha thought.

Doc Morrison didn’t sleep. He moved from one task to another with the calm efficiency of a man who’d been waiting years for permission to stop pretending. He sent messengers. He sealed ledgers. He swore affidavits while his hands still shook.

By noon, half the town knew the truth.

Not rumors. Not speculation. Truth—with dates and names and numbers that didn’t care who your father was.

By sundown, everyone knew.

The army auditor arrived early. Two days early, in fact, riding hard with a face like stone and a patience worn thin by frontier corruption. He didn’t smile. He didn’t threaten. He just asked questions and wrote everything down.

That was worse.

Sterling raged when he realized the game was over. He promised retaliation. He promised consequences. He promised the town would regret choosing sides.

No one answered him.

Silence, it turned out, worked differently when fear had changed hands.

They held the trial in the territorial capital. Fort Laramie sent witnesses—not out of spectacle, but because people needed to see it end.

Martha testified.

Her voice shook at first. It steadied when she talked about the cage. About Mrs. Chen. About the whipping post that no longer stood because the town had burned it down themselves and used the iron for something better.

Thomas Wyn testified too.

He talked about his wife. About land stolen. About pressure disguised as law. About watching a town teach his daughter to disappear and realizing too late that survival without dignity was just another kind of death.

Ronan Cade never took the stand.

He stood at the back of the room instead, still as a shadow, watching everything with eyes that missed nothing. He wasn’t on trial. He never would be. The evidence against Sterling swallowed everything else whole.

The verdict came quick.

Guilty.

Seventeen counts.

Twenty years.

Cal Sterling folded like damp paper when his sentence was read. Ten years, far from Fort Laramie, far from anyone who knew his name.

Sheriff Cutler accepted his punishment quietly. Fines. A ban from law enforcement. A life lived knowing he’d waited too long to be brave.

Fort Laramie went home changed.

Not fixed. Not perfect. But changed in a way that mattered.

Rebuilding is quieter than rebellion.

It looks like meetings that run too long and arguments about ordinances and people learning how to disagree without blood in the dirt. It looks like women sitting together without fear of being laughed into silence. It looks like men learning how to listen.

Martha taught reading three nights a week. The class kept growing. People brought friends. Then brought questions. Then brought ideas.

Her father closed the store early sometimes just to sit and listen.

Ronan stayed.

That surprised everyone—including him.

He helped rebuild what he’d burned, hands steady, movements precise. He didn’t soften, exactly. But he learned where to stand so people felt safe near him. Learned how to exist in a place with walls and noise and faces that remembered.

Children trusted him first.

They always do.

Six months later, Thomas Wyn sold the store.

“Time,” he said simply, pushing the pouch of gold across the table. “Time for you to live something new.”

Martha cried then. Hard. Ugly. Honest.

Ronan paced holes into the floor until she found him and told him they were free.

They left in late October.

No chase. No shouting. Just a town gathered to say goodbye properly this time.

Mrs. Chen hugged Martha like family. Doc Morrison pressed books into her hands. Old Peter cried without apology.

Fort Laramie didn’t forget them.

The valley was real.

Sheltered. Quiet. Water running clear and cold year-round. They built the cabin together, learning each other’s tempers and rhythms the way you only can when the work is heavy and necessary.

Martha read her mother’s letters by firelight.

Ronan learned his letters slowly, stubbornly, joy breaking across his face when words finally made sense.

Winter trapped them in snow for weeks. They learned how to be still together. How to argue without cruelty. How to choose each other when there was nowhere else to go.

By spring, the cabin felt like home.

By summer, Martha knew she was pregnant.

Ronan didn’t speak for a full minute after she told him. Just sat there, breathing, hands shaking like he didn’t trust the world not to take this too.

Then he laughed. Then he cried. Then he held her like she might vanish if he didn’t.

Their daughter came in January.

They named her Catherine.

She had Martha’s stubborn mouth and Ronan’s winter-gray eyes and a voice that made it very clear she intended to be heard.

Fort Laramie sent gifts.

They went down twice a year after that. Martha taught. Ronan helped build. Catherine learned early that courage wasn’t loud and strength didn’t always look like force.

Years later, Martha stood in the square with her daughter where the whipping post used to be.

A fountain splashed there now. Children ran through it in summer, shrieking with joy.

“Why here?” Catherine asked.

“Because this is where I learned what I was worth,” Martha said. “And where I learned that one person standing up can change more than they ever expect.”

“Did it hurt?”

“Yes,” Martha said honestly. “But staying quiet hurt worse.”

They rode back to the mountains that evening.

Back to the cabin.

Back to the quiet.

Back to a life built from courage, choice, and love that refused to stay small.

And somewhere in Fort Laramie, the story lived on—not as legend, not as myth, but as memory.

A reminder.

That sometimes the bravest thing you can do is step forward, take the blow, and refuse to let the world stay cruel just because it’s always been that way.

THE END