On the morning of April 14, 1847, spring sunlight spilled across the galleries of Louisiana’s plantation country, illuminating the white columns of Bellamont House and the manicured gardens meant to project refinement, order, and success. Inside, everything appeared as it should: polished floors, silver laid for breakfast, servants moving quietly through familiar routines.

And yet, before the day was done, a single gesture—framed as an act of generosity—would poison every relationship in that house.

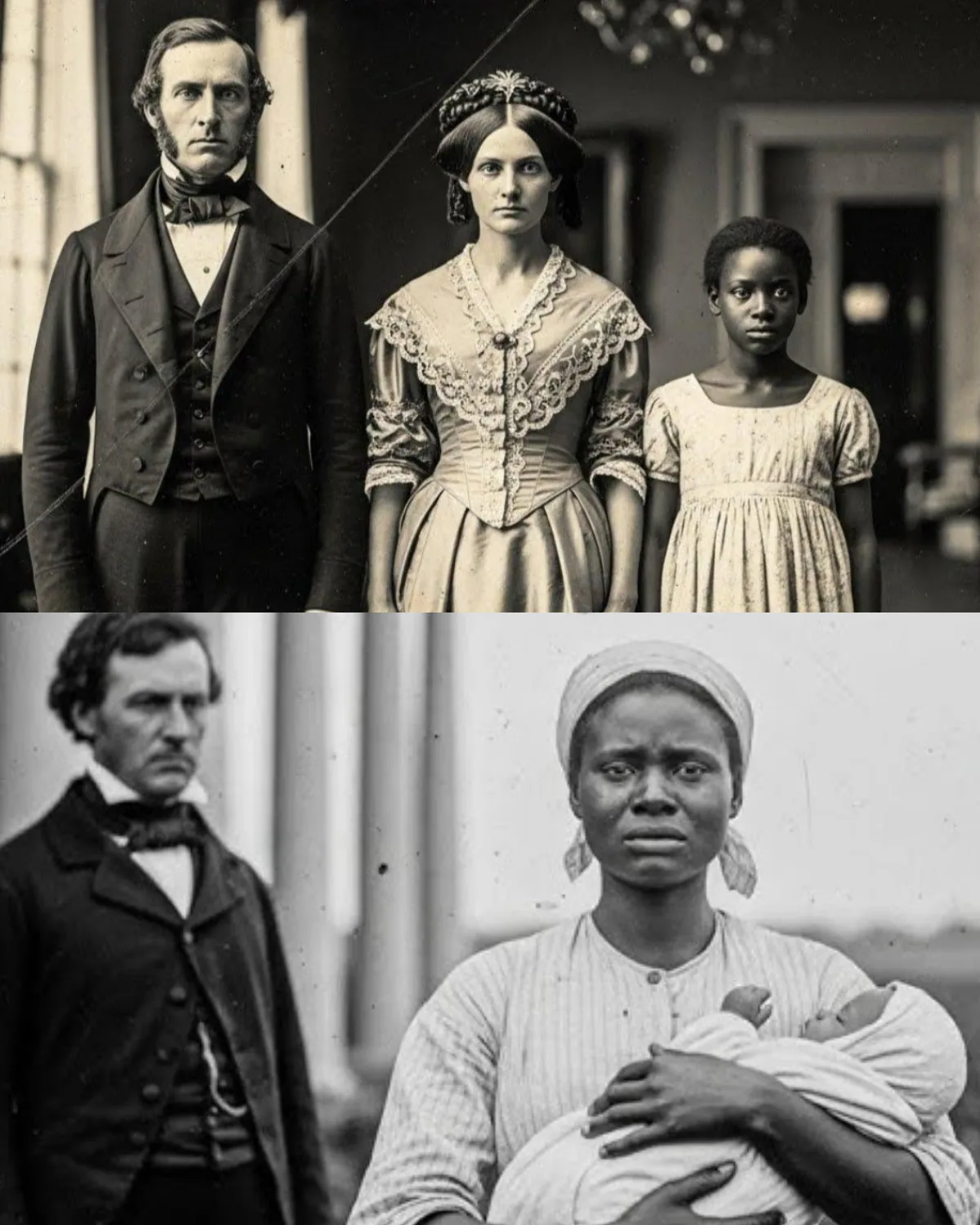

Henri Laval, a wealthy landowner and cotton speculator, was celebrating his ninth wedding anniversary with his wife, Celeste Laval. Among the flowers, the fine china, and the formal courtesies, Henri had prepared what he considered a fitting gift: a twelve-year-old enslaved girl named Rose, purchased days earlier from a Mississippi estate for two hundred dollars.

Rose was presented not in wrapping paper, but in a new cotton dress. She stood silently in the morning room, eyes lowered, hands folded, while Henri explained that she would now serve Madame Laval personally—assisting with her wardrobe, her hair, and her daily routines.

Celeste smiled and accepted the gift.

What she understood in that instant—what no one dared say aloud—was that this child bore her husband’s face.

A Secret Born in Mississippi

Rose’s story did not begin in Louisiana. She was born in 1835 on a smaller plantation in Mississippi, at a time when Henri Laval was still a young bachelor, ambitious and restless, moving between estates as he built his fortune in cotton.

Rose’s mother, Dinina, was an enslaved seamstress known for her intelligence and quiet dignity. Like countless other enslaved women, she lived in a world where consent was a fiction and protection did not exist. What passed between her and Henri left no written record—no diary, no confession—but it left a child.

That child, Rose, grew lighter-skinned as she grew older. Her eyes, her jaw, the tilt of her head all echoed Henri’s features with uncomfortable clarity. The men who owned the Mississippi plantation understood the danger of that resemblance. They also understood Henri’s rising importance. So the matter was buried. Dinina and her daughter were kept, well-treated enough to avoid scandal, invisible enough to preserve reputations.

Then the old plantation owner died. Assets were liquidated. Slaves were sold.

And Rose—twelve years old—was put on the market.

The Purchase That Should Never Have Happened

When Henri learned Rose was to be sold, he intervened. Officially, it was a business transaction. Unofficially, it was a catastrophic moral choice.

He told himself he was protecting her. That buying her was better than letting her fall into unknown hands. What he refused to confront was the cruelty of bringing his own daughter into his household as property—and then handing her to his wife as a gift.

The journey from Mississippi to Louisiana took four days. Rose traveled chained in a wagon with other enslaved people, sleeping on the ground, fed just enough to survive. It was her first experience of being treated explicitly as cargo.

Bellamont House must have seemed enormous when she arrived: tall white columns, wide galleries, dozens of enslaved workers whose lives revolved around the cotton fields and the demands of the main house. From the first day, the older servants noticed something unsettling in the way Henri looked at her.

They also noticed the way Celeste watched.

A Mistress Who Understood Power

Celeste Laval was not a woman given to public cruelty. She prided herself on elegance, restraint, and control. She never beat Rose. She never starved her. Instead, she subjected the girl to something more precise.

Rose was kept constantly under Celeste’s supervision. Tasks were assigned that could never be done correctly. Standards shifted without warning. Rose was criticized not loudly, but endlessly. Hours were wasted standing still, holding objects, waiting for approval that never came.

This was punishment without bruises—designed to erase confidence and reinforce helplessness.

Henri, bound by guilt and cowardice, did nothing. To intervene would be to admit the truth. And the truth was incompatible with his standing as a respectable white planter.

The Moment the Secret Spoke Aloud

By 1852, Rose was fifteen—and newly vulnerable. A plantation overseer noticed her. His attention escalated. Rose understood the danger immediately. When she turned to Celeste for protection, the response was cold and final.

“You are not a child,” Celeste told her.

“Handle it yourself.”

Weeks later, the inevitable happened. The overseer attacked Rose in the laundry house. She fought back, injured him, and fled—straight into Henri’s study.

Bleeding. Terrified. Desperate.

“You’re my father,” she said.

“Please help me.”

For a moment—just one—Henri saw her not as property, not as a problem, but as his child.

Then Celeste entered the room.

And Henri fell silent.

Revenge Disguised as Justice

Three days later, Rose was arrested.

Celeste accused her of stealing a gold brooch—an heirloom. The brooch was “found” among Rose’s belongings. Enslaved people could not testify. The outcome was predetermined.

At the trial, as the judge prepared to convict her, Henri stood.

And finally—publicly—he chose.

He declared Rose innocent. He contradicted his wife in open court. The charges were dismissed. The courtroom erupted in whispers.

Celeste’s humiliation was complete.

Freedom Bought Too Late

Henri knew what would come next. He also knew he could no longer live with himself if he did nothing.

Within days, he arranged Rose’s escape—disguised as a sale. She was sent to abolitionists in Texas, given gold, and a letter of manumission. From there, she crossed into Mexico, then traveled north through the Underground Railroad.

Rose reached Illinois in 1854.

She was free.

She built a life as a seamstress. She married. She raised children who were taught to read, to write, and to live unowned.

She never spoke of Bellamont House again.

What Remained Behind

Henri Laval died in 1856, consumed by guilt and isolation. Celeste lived on, bitter and alone, until the Civil War stripped her world of its power and purpose. Bellamont House fell into ruin—another silent monument to the Old South’s violence and self-deception.

Rose lived until 1903. She died surrounded by descendants who never knew the full truth of her childhood.

Her legacy was not the suffering she endured—but the freedom she claimed.

Why This Story Matters

This is not a story about one cruel man or one vengeful woman.

It is a story about a system that turned fathers into owners, wives into wardens, and children into currency.

It shows how slavery corrupted every human relationship it touched—and how even “kind” or “respectable” people participated in unspeakable harm simply by choosing comfort over conscience.

And it reminds us of something essential:

Survival is not the same as justice.

Freedom earned late is still freedom.

And the people history tried hardest to erase are often the ones who endure.