In January 1945, while most of the world focused on frozen forests, burning tanks, and the slow collapse of Hitler’s last great gamble, the most dangerous battle in Western Europe was not being fought with artillery or aircraft. It was being fought with words, egos, and a single sheet of paper in a quiet office. No soldiers died in this battle, no cities were destroyed, and yet the future of the entire Allied command structure hung in the balance.

It began, absurdly, with a smile.

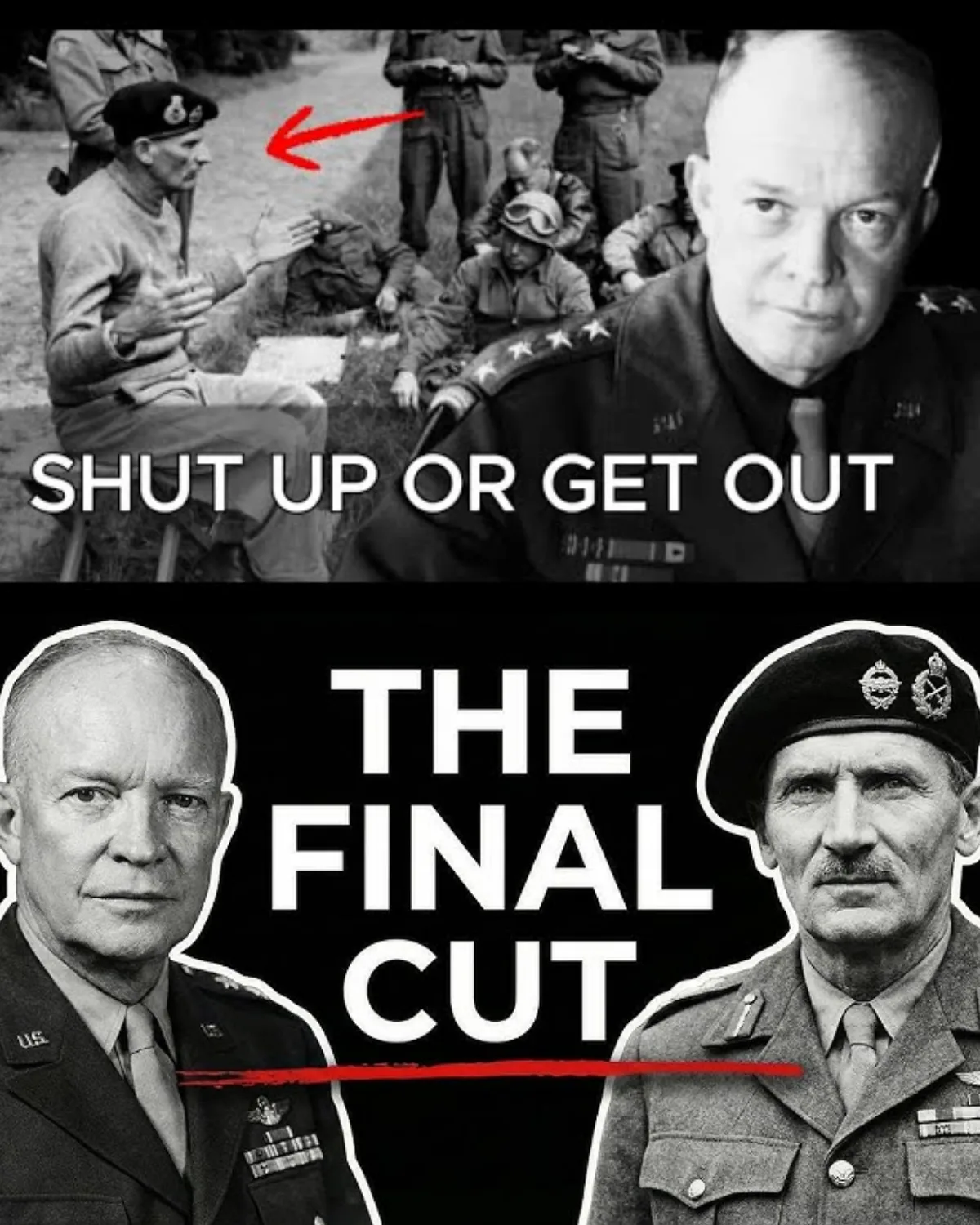

On January 7th, 1945, inside a British press tent near the front lines, Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery stood before a bank of microphones. Snow lay three feet deep outside. The Battle of the Bulge had just ended. Tens of thousands were dead. Entire towns were ruins. But Montgomery looked relaxed, almost pleased with himself. He spoke calmly, confidently, as cameras flashed and reporters scribbled.

He described the battle as “one of the most tricky I have ever handled.” He spoke of deploying “the whole available power.” He repeated the word “I” like a drumbeat. To British journalists, it sounded like a victory speech. To Montgomery, it was simply the truth as he saw it: a narrative in which he had personally rescued a floundering alliance and restored order to chaos.

Three hundred meters away, in Supreme Allied Headquarters, General Dwight D. Eisenhower was reading the transcript.

Eisenhower did not shout. He did not throw the paper. He simply sat in silence, hands trembling with a kind of cold, unfamiliar anger. For three years, he had tolerated Montgomery’s arrogance. He had absorbed insults, swallowed public slights, and defended the British general against American resentment because he believed the alliance mattered more than his own pride. But this time, something had broken.

Montgomery had crossed the one line Eisenhower could not ignore: he had publicly humiliated the American army.

To understand why this moment was so explosive, one must understand the relationship between these two men. Eisenhower and Montgomery were not rivals in the usual sense. They represented two completely different philosophies of war.

Eisenhower was a coalition general. His genius was not in tactics, but in people. He understood that modern war was not won by the best battlefield maneuvers, but by keeping fragile alliances from collapsing under pressure. He managed egos, smoothed conflicts, negotiated between nations, and treated command as a political art.

Montgomery, by contrast, was a pure field general. He saw war as a technical problem: get the forces right, apply overwhelming power, and move forward methodically. He had defeated Rommel at El Alamein and become a national hero in Britain. From that moment on, he developed an unshakable belief that he alone truly understood modern warfare.

In Montgomery’s mind, Eisenhower was not a real general at all. He was a staff officer who had been promoted too far, a politician in uniform who lacked the instincts of a true battlefield commander. Montgomery believed the Americans needed him. He believed they were amateurs playing a game he had already mastered.

For years, Eisenhower tolerated this attitude. Churchill begged him to. London protected Montgomery because he was a symbol of British pride. The unspoken agreement was simple: Monty would provide experience, the Americans would provide manpower and industrial power, and Eisenhower would hold it all together.

But by late 1944, that balance had shifted. The United States was no longer the junior partner. It was supplying the vast majority of troops, tanks, aircraft, and fuel. Britain was exhausted. The empire was fading. Montgomery, however, was still fighting a 1942 war in a 1945 world. He had not adjusted to the new reality.

When the Germans launched the Ardennes offensive on December 16th, 1944, chaos ripped through the Allied command. German forces smashed into American lines, creating a massive wedge that physically separated General Omar Bradley’s headquarters in the south from his two largest armies in the north. Communications collapsed. Units lost contact. The front fractured.

Eisenhower faced a brutal decision. Bradley could no longer effectively command the northern armies. For the sake of operational unity, Eisenhower temporarily placed two American armies under Montgomery’s control. It was a pragmatic move. Militarily sensible. Politically disastrous.

To American generals, it felt like betrayal. Bradley was humiliated. Patton was furious. But they obeyed. They expected Montgomery to act as a caretaker, a temporary steward until the crisis passed.

Instead, Montgomery arrived like a conqueror.

He rejected American defensive plans, reorganized their lines, canceled counterattacks, and spoke to seasoned U.S. commanders as if they were incompetent cadets. “I shall tidy up this mess,” he reportedly said, a phrase that spread through American headquarters like poison.

He forced Bradley to travel to him rather than visiting Bradley’s headquarters. When they met, Montgomery lectured him on basic tactics. Bradley sat in silence, grinding his teeth, absorbing humiliation for the sake of the alliance.

Montgomery did stabilize the northern front. That cannot be denied. But in doing so, he destroyed what little goodwill remained between himself and the Americans. He won on the map and lost in the minds of his allies.

And then he bragged about it.

At the January 7th press conference, Montgomery presented a version of the Battle of the Bulge that bordered on fantasy. He barely mentioned the defense of Bastogne by the U.S. 101st Airborne. He ignored Patton’s brutal winter march to relieve the city. Instead, he painted a picture in which American forces were collapsing until he stepped in to rescue them.

British newspapers celebrated. Headlines declared that “Monty saved the Yanks.” To the American command, it felt like a public execution.

Bradley told Eisenhower he would resign rather than serve under Montgomery again. Patton demanded action. The entire U.S. high command was in revolt.

Eisenhower understood something Montgomery did not: this was no longer a personality conflict. It was now a strategic threat. If American generals lost faith in the Allied command structure, the coalition itself could fracture.

So Eisenhower did the one thing he had never done before. He stopped compromising.

In his office, in silence, he began drafting a cable to General George Marshall in Washington. The words were calm, precise, and lethal. He described the breakdown of trust. He explained that Montgomery’s behavior had made the command structure unworkable.

Then he wrote the ultimatum.

If Montgomery was not removed, Eisenhower would resign.

It was not a bluff. Eisenhower was offering the Combined Chiefs of Staff a choice: the supreme commander of all Allied forces or a single British field marshal. The equation was simple. Him or me.

He showed the draft to Montgomery’s chief of staff, Freddie de Guingand. When de Guingand read it, the blood drained from his face. He realized instantly what was happening. Eisenhower was preparing to fire the most famous general in the British Empire.

De Guingand raced through a blizzard to Montgomery’s headquarters. When he arrived, Montgomery was cheerful, unaware of the disaster he had created.

“Ike is going to fire you,” de Guingand said. “And Churchill cannot save you.”

Montgomery laughed at first. He thought it was impossible. Eisenhower needed him. The alliance needed him. De Guingand shook his head and described the letter, the tone, the finality.

The reality hit Montgomery like a physical blow. The smirk vanished. For the first time in the war, the great field marshal was terrified. He realized he had miscalculated everything. He was not dealing with a weak politician. He was dealing with the most powerful man in the Western world.

The next morning, Montgomery wrote a letter.

It was not arrogant. It was not defensive. It was total surrender.

“Dear Ike,” it began. “I am distressed that my note may have upset you. I am your very devoted subordinate.”

He promised obedience. He promised restraint. He promised to stop talking.

Eisenhower read it without satisfaction. He placed the firing order he had drafted into a secret file and accepted the apology. The crisis was over. Publicly, the alliance survived. Privately, something fundamental had changed.

Eisenhower never trusted Montgomery again.

From that moment on, Montgomery was sidelined. He kept his rank, his medals, his reputation at home, but he lost influence. Eisenhower increasingly relied on American commanders. The final drive into Germany became an American show. When the Rhine was crossed, it was American forces who took the strategic glory.

Montgomery staged his own elaborate crossing later, but it no longer mattered.

The real significance of that January day was not tactical. It was historical. It marked the moment when leadership in the Western alliance passed definitively from Britain to the United States. The empire gave way to the superpower.

Montgomery believed he was bigger than the war. Eisenhower proved that no one was.

The Battle of the Bulge is remembered for snow and tanks and heroism. But the most dangerous battle of all was fought with a pen, in a warm office, when a general finally told another general to shut up or get out.