The Execution of Nazi Collaborator — Pietro Caruso Chose 335 Innocents to Die

The Man Who Chose 335 to Die

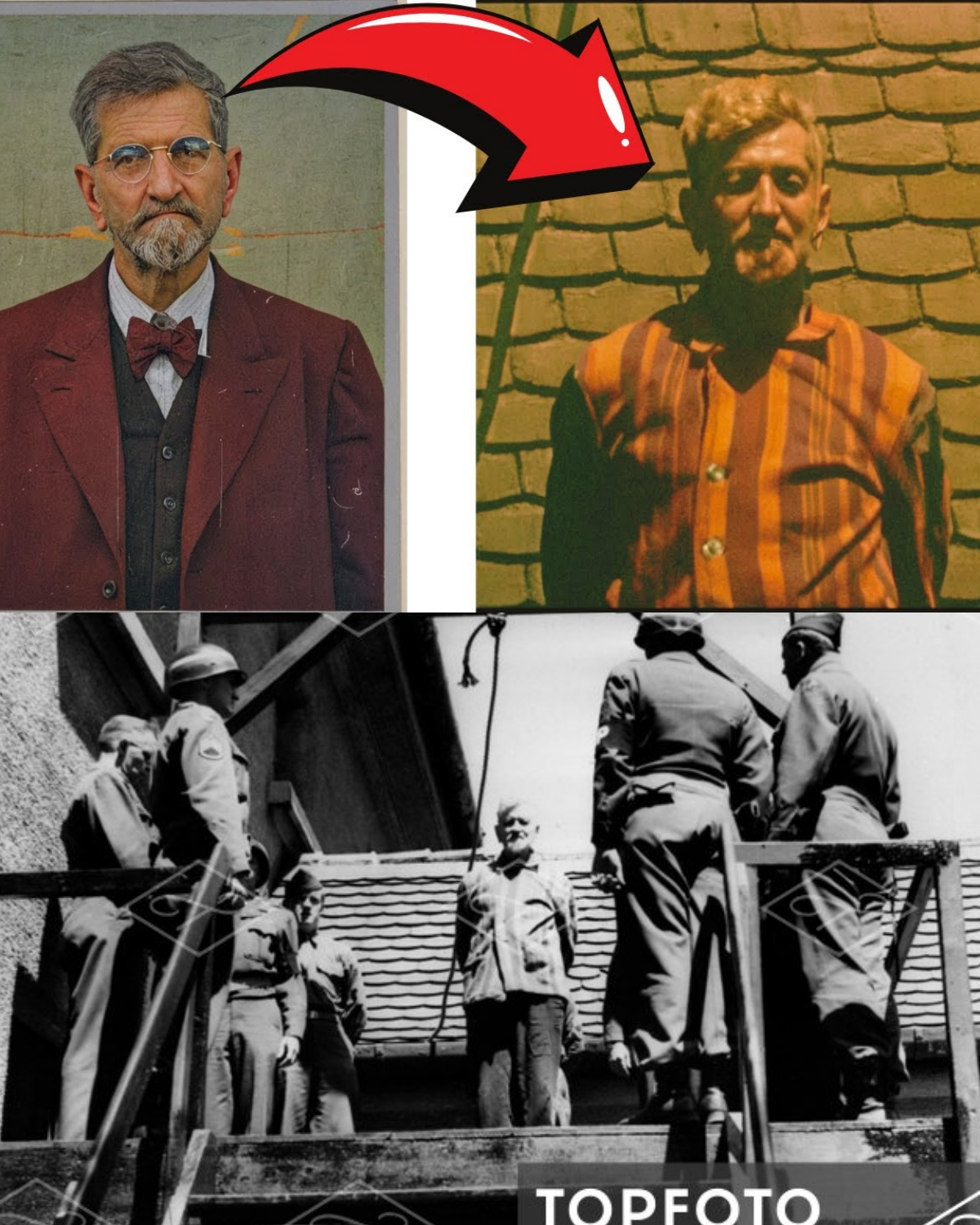

The Execution of Pietro Caruso

Rome, September 22, 1944

He could barely stand.

The man being led across the courtyard leaned heavily on his crutches, his body weakened by illness, stress, and the sudden collapse of everything he had believed permanent. Only months earlier, his name had been spoken in whispers across Rome—spoken carefully, fearfully. Now it was announced aloud, without hesitation.

Pietro Caruso was about to be executed.

The irony was not lost on the crowd. This was a man who had ordered arrests at dawn, who had sent others to die without trial, without mercy, without even learning their names. Now he stood before a firing squad, facing the same finality he had once dispensed so casually.

Rome Under the Boot

When German forces occupied Rome in September 1943, following Italy’s armistice with the Allies, the city entered one of its darkest chapters. The Nazis ruled openly, but they could not govern alone. They required collaborators—locals who understood the streets, the networks, the people.

Caruso was exactly that man.

As police chief of Rome under the Fascist-controlled Italian Social Republic, Caruso became the city’s internal executioner. He did not merely follow German directives. He enforced them with zeal.

Partisans were hunted relentlessly. Civilians were arrested on suspicion alone. Jews were rounded up, interrogated, and handed over to German authorities—many of them never seen again. Under Caruso, the police headquarters became a place of dread. Fear was policy. Brutality was routine.

Caruso believed in the permanence of power. He believed the Germans would win. He believed that loyalty would protect him.

He was wrong.

The Massacre That Defined Him

On March 23, 1944, Italian resistance fighters attacked a German police regiment on Via Rasella, killing 33 German soldiers. The Nazi response was swift and merciless. Adolf Hitler ordered retaliation: ten Italians executed for every German killed.

The final number would be 335.

The site chosen was the Fosse Ardeatine, a network of caves on the outskirts of Rome. What followed was one of the most infamous war crimes in Italian history.

Caruso was not a bystander.

He assisted directly in compiling the list of victims. Political prisoners. Jews. Random detainees. Men dragged from cells to meet an execution they could not comprehend. There were no trials. No appeals. Only names on paper and bullets in the dark.

Inside the caves, the victims were shot, one by one, and buried under explosives meant to erase the evidence. Instead, the massacre became a permanent scar on Rome’s memory.

From that moment forward, Caruso’s fate was sealed—whether he knew it or not.

Collapse of Power

On June 4, 1944, Allied forces liberated Rome. German troops withdrew north. The Fascist administration evaporated almost overnight.

Caruso attempted to flee. He failed.

Arrested by Italian authorities, he was placed on trial for war crimes and collaboration. The courtroom was filled with survivors, witnesses, and families of the dead. Evidence was overwhelming. Documents bore his signature. Testimony described his direct involvement.

Caruso did not deny his role. He argued necessity. He argued obedience. He argued that refusing German orders would have meant his own death.

The court was unmoved.

In a city still mourning its dead, the verdict came swiftly: death by firing squad.

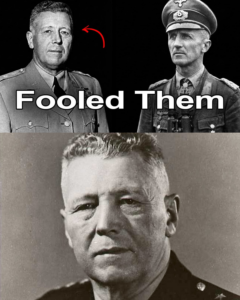

The Execution

On the morning of September 22, 1944, Caruso was brought to the execution site. He was visibly frail, dependent on his crutches, his former authority reduced to a physical struggle to remain upright.

There were no speeches. No defiant declarations. Only the presence of a man confronting the final consequence of his choices.

The firing squad took position. Rifles were raised. The command was given.

The shots echoed across Rome.

Pietro Caruso collapsed to the ground, his life ending not in secrecy, but in full public view.

Justice, or Closure?

The crowd watched in silence. There was no cheering. No celebration. Only a heavy stillness.

For some, Caruso’s death was justice long delayed. For others, it was merely a symbolic end—one life taken for 335 already lost. No execution could restore what had been destroyed in the caves. No bullet could return the fathers, sons, brothers, and husbands who had been murdered.

Yet the moment mattered.

Caruso had ruled through fear, convinced that power insulated him from consequence. His execution shattered that illusion. It declared, publicly and unmistakably, that collaboration carried a price.

The Legacy of a Collaborator

History remembers Caruso not as a tragic figure, but as a willing participant in atrocity. He was not a faceless cog. He was a decision-maker. A man who chose compliance over conscience, authority over humanity.

The Fosse Ardeatine remains today as a memorial—silent, solemn, unyielding. Each name carved into stone stands in judgment far more enduring than any firing squad.

Caruso’s execution did not heal Rome.

But it marked a boundary.

A line drawn between those who enforced terror and those who suffered under it. A reminder that even in the chaos of war, choices matter—and that some choices echo long after the gunfire fades.

He had chosen 335 to die.

In the end, history chose to remember him for exactly that.