“I Am Not Guilty… Please Get It Over With”

The Final Hours of Dr. Claus Schilling

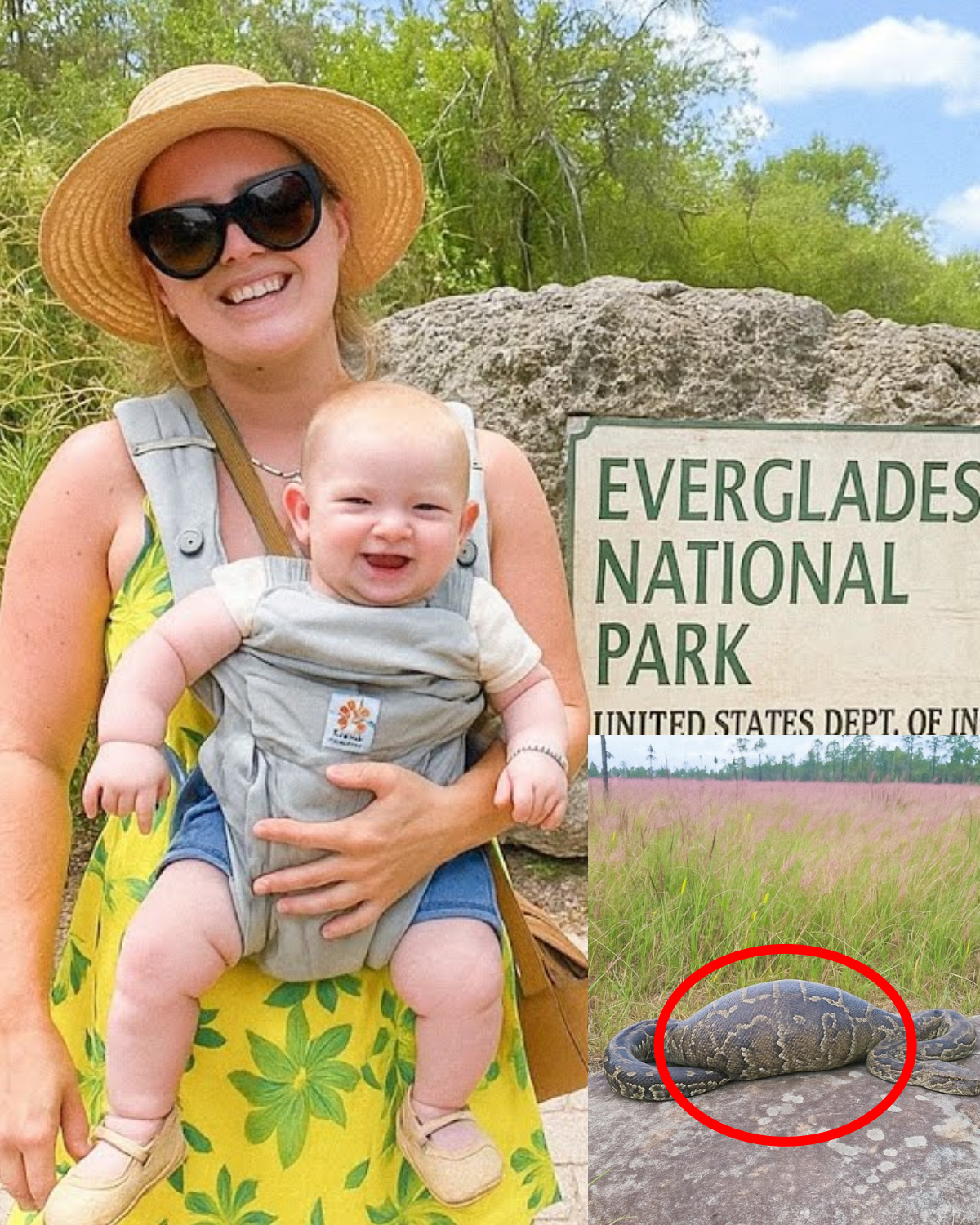

Landsberg Prison, Bavaria — May 28, 1946

The prison corridor smelled of disinfectant and old stone. Dawn had not yet broken, but the day was already decided. A man in his seventies sat on a wooden bench, shoulders slumped, hands trembling—not from fear alone, but from age, exhaustion, and the slow collapse of a life once shielded by titles and authority.

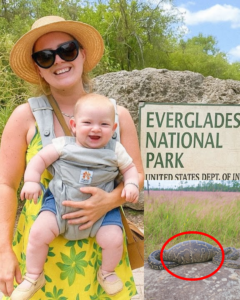

His name was Claus Schilling.

Once, he had been addressed as Professor. Once, he had spoken at conferences, published papers, and claimed the prestige of science. Now, in the final hours of his life, he was simply Prisoner Number 5—waiting to be hanged.

When the guards approached, Schilling did not resist. He looked up, pale-eyed, and spoke the words that would follow him into history:

“I am not guilty… please get it over with.”

The Doctor Who Believed in Himself

Claus Schilling was not a marginal figure in Nazi medicine. Born in 1871, he was already an established physician long before Adolf Hitler rose to power. By the time the Third Reich began, Schilling was an old man—but one who believed his life’s work was not finished.

He was obsessed with malaria.

To Schilling, malaria was not merely a disease. It was a puzzle. A battlefield. And in the warped moral universe of Nazi Germany, it was also an opportunity.

When Heinrich Himmler’s SS offered him unrestricted access to human test subjects at Dachau concentration camp, Schilling accepted without hesitation. He did not see prisoners. He saw data.

Dachau: The Laboratory Without Consent

Between 1942 and 1945, Schilling conducted malaria experiments on hundreds of prisoners—Poles, Russians, Jews, Roma, and others deemed expendable by the regime.

They were deliberately infected.

Some were bitten by malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Others were injected directly with the parasite. None gave consent. Many were already weakened by starvation, forced labor, and abuse.

Schilling tested drug after drug. Dosage after dosage. Some victims were denied treatment entirely, left to convulse with fever until their organs failed. Others were pushed beyond survivable limits, their suffering meticulously recorded.

Witnesses later described prisoners screaming through nights of delirium, begging for water, for mercy, for death.

Schilling called it research.

The Illusion of Scientific Purpose

At trial, Schilling would argue that his experiments had value. That malaria was a legitimate military concern. That soldiers were dying of it at the front. That sacrifices were necessary.

But the prosecution dismantled this defense piece by piece.

The experiments were sloppy. The records inconsistent. The deaths excessive. There was no therapeutic justification—only obsession and cruelty masquerading as science.

Most damning of all: Schilling continued even when results proved useless.

This was not about saving lives.

It was about power.

The Doctors’ Trial

After Germany’s collapse, Schilling was arrested and brought before the American military tribunal in what became known as the Doctors Trial.

He was the oldest defendant in the courtroom.

Other accused physicians hid behind bureaucracy or ideology. Schilling did something different—he spoke freely. He lectured the court. He defended his methods. He insisted history would vindicate him.

Survivors testified.

Former prisoners described being used as disposable instruments. They spoke of friends who died screaming in isolation wards. They pointed to Schilling as the man who ordered it, supervised it, and never stopped it.

The court listened.

The verdict was unanimous.

Guilty of Crimes Against Humanity

Schilling was convicted of crimes against humanity—not for being a Nazi, but for violating the most fundamental boundary of medicine: do no harm.

The sentence was death.

Unlike some defendants, he did not shout. He did not collapse. He merely nodded, as if the court had confirmed an inconvenience rather than pronounced his end.

Privately, however, witnesses noted his fear growing as execution day approached.

The man who had once played God was discovering mortality.

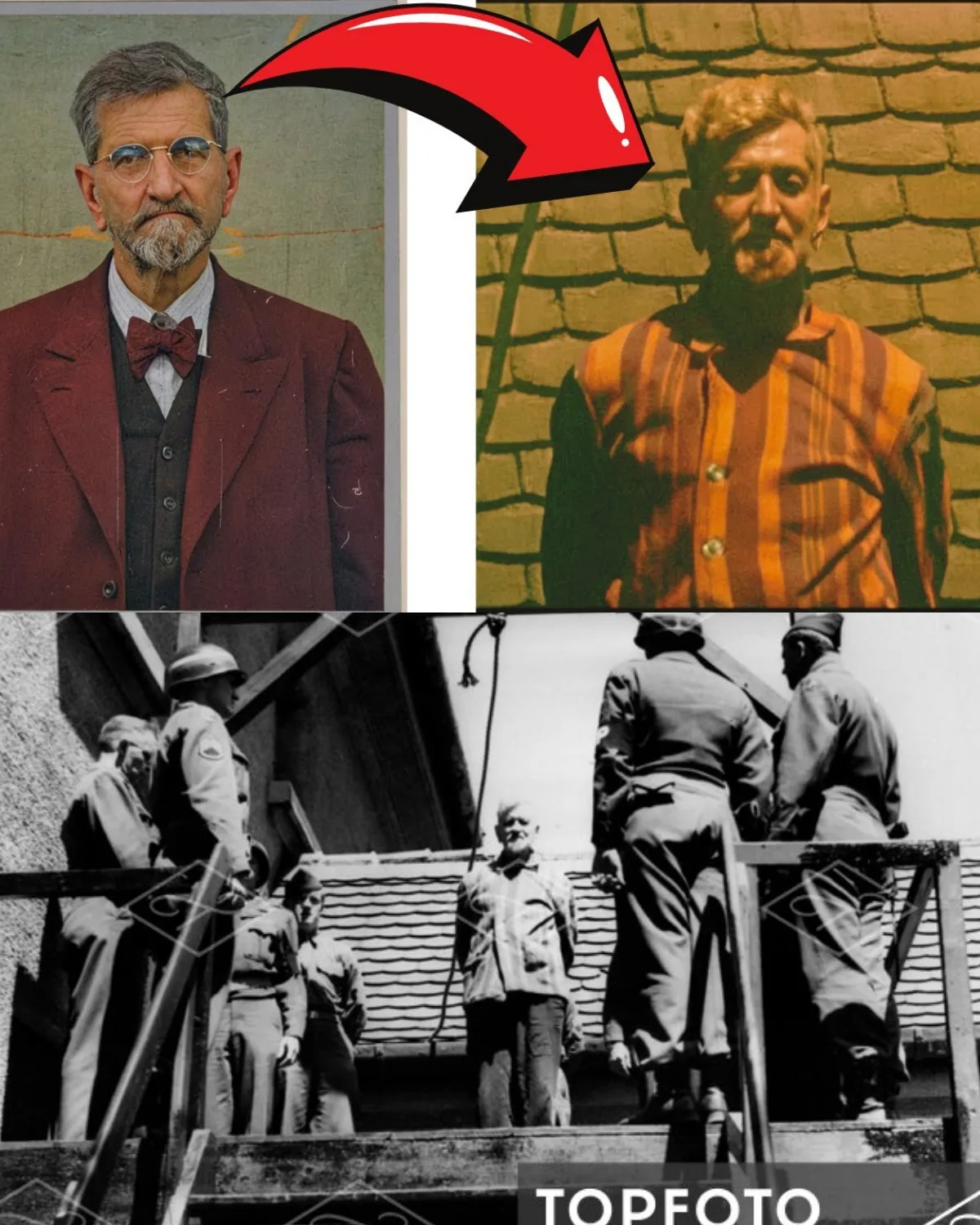

The Walk to the Gallows

On the morning of May 28, 1946, Schilling was escorted to the execution chamber at Landsberg Prison, where other Nazi war criminals had already met their end.

The gallows stood silent.

There would be no speeches. No last-minute reprieve. No audience beyond officials and guards.

Schilling requested mercy—not forgiveness, but speed.

“I am not guilty,” he repeated.

But the rope did not argue.

Death Without Absolution

At 1:10 a.m., the trapdoor opened.

There was no dramatic final moment. No revelation. Only the physical end of an old man whose intellect had outlived his conscience.

The execution was swift.

Clinical.

Almost appropriate.

Aftermath: The Legacy of a Warning

Claus Schilling’s death did not erase his crimes. It did not restore the lives he destroyed. But it did something else—it helped redraw the moral boundaries of science itself.

From the ashes of the Doctors’ Trial emerged the Nuremberg Code, a foundational document of modern medical ethics. Voluntary consent. The right to withdraw. The absolute prohibition of unnecessary suffering.

Every ethical standard taught in medical schools today carries the shadow of men like Schilling.

Not as pioneers.

But as warnings.

The Final Question

Can such crimes ever be forgiven?

History does not answer with absolution. It answers with memory.

Schilling died insisting on his innocence. But innocence is not self-declared. It is measured—by actions, by consequences, and by the suffering left behind.

He asked for it to be “gotten over with.”

For him, it was.

For his victims, it never was.