The G.I.s Laughed at the “Apache Tracker” — Until Audie Murphy Told Them to Lower Their Rifles…

Lower your rifles. The words cut through the cold air of the Voge forest like a blade, sharp and final. Every man froze. Audi Murphy stood between his platoon and a soldier they had mocked for three days straight. A man they had called primitive backwards, a relic from another time. The Apache tracker had raised his hand in a silent warning, and the GIs were seconds away from ignoring him, pushing forward into what looked like empty woods shrouded in fog.

But Murphy saw something they didn’t. Something in the stillness of the trees, in the way the mist hung too perfectly, in the absolute silence that had fallen over the forest like a held breath. Death was watching them, and it was waiting for them to make noise. 3 days earlier, the men of the Third Infantry Division had been given a mission that no one wanted. push through the Voge Mountains, scout enemy positions, identify artillery placements, and report back without getting killed.

Simple on paper, a nightmare in reality. The forest was a living hell. Thick fog clung to the trees like a burial shroud, so dense that visibility dropped to less than 20 ft on good days. Rain turned the ground into a slippery mess of mud and exposed roots that grabbed at boots and twisted ankles. The trees grew so close together that moving in formation was impossible. Every step forward felt like walking into a trap, and the men knew it in their bones.

The Germans knew this terrain intimately. They had spent months fortifying the Voge, laying mines along the trails, setting up machine gun nests in concealed positions, and turning the mountain passes into carefully orchestrated killing zones. They had observation posts on every ridge, snipers in every tree line, and artillery pre-sighted on every approach route. The Americans were walking blind into enemy territory, and the casualty rates showed it. Companies that went into the Voge at full strength, came out with half their men dead or wounded.

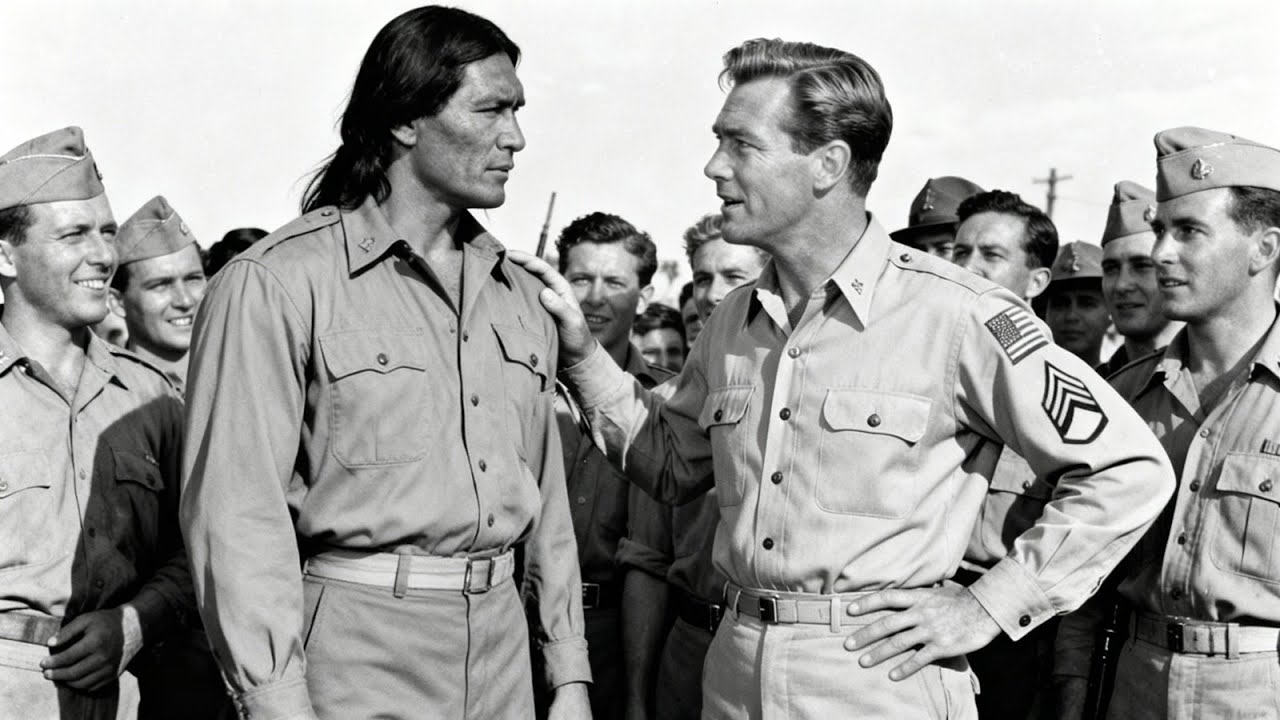

The Third Infantry Division had already lost hundreds of soldiers in these cursed mountains, and there was no end in sight. That’s when Lieutenant Thaddius Crawford introduced the platoon to their new scout. His name was Joseph Tall Mountain. He was Apache, born and raised in the high deserts of Arizona, and he had been trained since childhood in the old ways of tracking and survival. The army had quietly recruited Native American soldiers specifically for their skills in reconnaissance, land navigation, and moving unseen through hostile territory.

Joe didn’t carry himself like the other GIS. He moved quietly, almost invisibly, his footsteps making no sound, even on the noisiest terrain. He watched everything with dark, intelligent eyes that seemed to see layers of information the others missed, the way the birds flew, the way the wind shifted direction, the way the ground felt under his boots, the patterns of disturbed leaves, the smell of the air. To him, the forest wasn’t a death trap or an enemy. It was a language complex and ancient, and he could read it fluently.

The men didn’t see it that way. To them, Joe was a curiosity at best and a liability at worst. They had been trained in modern warfare, in tactics developed at militarymies, in the use of technology and firepower to overwhelm the enemy. The idea that someone would navigate by feeling the ground or watching birds seemed absurd, even dangerous. Private Tommy Henderson was the first to crack a joke. He was 18 years old, skinny as a rail with a nervous energy that never quite settled.

He had grown up in Brooklyn, surrounded by concrete and noise, and the deep forest terrified him in ways he couldn’t articulate. Humor was his defense mechanism, his way of processing fear. So when Joe knelt down to examine a patch of disturbed soil, running his fingers through the dirt and studying it with intense concentration, Tommy whispered loud enough for everyone to hear, “Look at that, boys. The great tracker is communing with the spirits. Maybe he’ll ask the trees where the Germans are hiding.

Should we hold a seance? A few of the men chuckled nervously. Corporal Mike Russo, a stocky 22-year-old from Boston with a chip on his shoulder and something to prove, smirked and shook his head. This is what they send us? A guy who talks to dirt? We’re supposed to trust our lives to someone who thinks nature has all the answers. Joe didn’t react. He had heard it all before in training camps from Georgia to California, in mesh halls and barracks and transport trucks.

Native American soldiers were often treated as outsiders, even by the men they were supposed to fight alongside. Some officers respected their skills and utilized them effectively. Others saw them as a gimmick, a novelty, something exotic to brag about in letters home. The enlisted men were usually worse, viewing native scouts with a mixture of suspicion and mockery. Joe had learned early to ignore the jokes, to let the words slide off without leaving marks. His job wasn’t to make friends or win popularity contests.

It was to keep these men alive, to use everything his grandfather and uncles had taught him to navigate terrain that would kill them otherwise, even if they didn’t believe he could, even if they laughed while he did it. Sergeant Frank Dalton, the platoon leader, was a hard man from the south side of Chicago. He was 31 years old, which made him ancient by infantry standards, and he had the scars to prove it. He had seen action in North Africa, waiting through the blood and sand of Casarine Pass.

He had fought in Sicily, clearing towns house by house, while snipers picked off his friends. He had landed at Serno and pushed through the Italian mountains in conditions that made the Voge look pleasant. Dalton didn’t have time for anything that didn’t produce tangible results. He wasn’t cruel to Joe, but he wasn’t patient either. When Joe suggested they move off the main trail and take a longer route through denser cover, Dalton hesitated, his jaw tightening. That’ll add at least an hour to our march.

We’re already behind schedule. Division wants us at the observation point by nightfall. Joe met his eyes steadily, his voice calm and certain. The trail is too open. If they have observers on the ridges, they’ll see us coming from a mile away. We’ll be sitting ducks for artillery. Dalton looked at the map, then at the men standing in the cold rain, then back at Joe. The weight of command pressed down on him. Fine, but if we get bogged down in the mud and miss our objective, it’s on you.

They took the longer route. It was slow, miserable work that tested everyone’s patience and endurance. The men grumbled constantly, their complaints forming a low background noise of discontent. Their boots sank into the muck with every step, sometimes going in up to the ankle. Branches slapped at their faces, leaving scratches and welts. The cold rain found every gap in their uniforms, soaking through layers until they were chilled to the bone. Tommy kept up his commentary, his voice a mixture of humor and genuine frustration.

I bet the Apache spirits are real proud of this shortcut. My grandmother could navigate faster than this, and she’s been dead for 3 years. Russo laughed, a harsh bark of sound. Yeah, real tactical genius here. At this rate, the war will be over before we reach the observation point. We’ll die of old age instead of German bullets. Even Lieutenant Crawford looked uncomfortable, though he kept his thoughts to himself. He had been taught at West Point to trust his scouts, to defer to their expertise in matters of terrain and navigation.

But Joe’s methods didn’t match anything in the manual or any lecture he had attended. There were no compasses being consulted, no maps being checked, no radio calls for guidance, just instinct and observation, ancient skills that seemed out of place in a modern mechanized war. Audi Murphy didn’t say much during the march. He rarely did. At 19 years old, he was already one of the most respected soldiers in the division, though he didn’t act like it or seek attention.

He had grown up dirt poor in rural Texas, one of 12 children in a sharecropper family that barely survived from season to season. When his father abandoned them and his mother died, Murphy had fed his younger siblings by hunting in the woods with a borrowed rifle, tracking rabbits and deer through dense brush. He understood what Joe was doing in a way the others didn’t recognized it from his own childhood. Murphy watched the way Joe moved through the forest.

The way he paused every few minutes to listen with his entire body, the way he tested the wind direction with a wetted finger. The way his eyes constantly scanned the canopy and the ground simultaneously. It wasn’t superstition or primitive mysticism. It was survival, pure, and practical. Murphy had done the same thing back home, reading the land like a book written in a language most people never learned. He knew Joe wasn’t guessing or relying on luck. He was reading signs the rest of them couldn’t see, interpreting data they didn’t know existed.

That night, they made camp in a shallow ravine that offered some protection from the wind. The men were exhausted, cold, and hungry. They wanted hot food, warm fires, and a few hours of sleep that didn’t involve shivering. Joe insisted they avoid lighting fires. His voice quiet but firm. The smoke will give away our position. If they have patrols in this area, they’ll see it or smell it from a mile away. Tommy groaned theatrically, throwing his hands up.

So now we freeze to death instead of getting shot. What’s the difference? At least if we die warm, we’ll die comfortable. Dalton considered Joe’s advice carefully, weighing the risks. His men needed warmth and hot food to maintain morale and combat effectiveness. But if Joe was right, fires could get them all killed before morning. Finally, he nodded. No fires. Joe’s call. We eat cold rations and stay alert. The men huddled in their coats, chewing tasteless krations and cursing under their breath.

Some cursed the Germans. Some cursed the army. Most cursed Joe Tall Mountain. the Apache scout, who seemed determined to make their lives as miserable as possible. Murphy sat near Joe, methodically cleaning his rifle in the fading light. The repetitive motion was soothing, almost meditative. After a while, he spoke quietly. “You grow up hunting?” Joe glanced at him, surprised by the question. It was the first time anyone had tried to have an actual conversation with him since I was 5 years old.

My grandfather taught me. He said, “The land speaks to those who know how to listen. Most people are too loud to hear it.” Murphy nodded slowly, understanding completely. “Me, too. Had to feed my brothers and sisters after my mother passed. Spent more time in the woods than in school.” Joe studied him for a moment, seeing something in Murphy’s eyes that he hadn’t seen in the others. Recognition, respect, common ground. He went back to sharpening his knife, but the tension in his shoulders eased slightly.

It was a small thing, one quiet conversation in a cold forest, but it mattered. The second day was significantly worse. The fog was so thick they could barely see 10 ft ahead. A solid wall of gray that swallowed sound and distorted distance. It felt like moving through a dream or a nightmare. Joe moved even more cautiously now, stopping every few minutes to crouch low and listen with absolute concentration. The men grew increasingly impatient, their nerves fraying. They were exposed, vulnerable, moving through terrain where the enemy could be anywhere.

The waiting and the silence were almost worse than combat. At least in a firefight, you knew where the danger was. Here, it could come from any direction. At any moment, Russo muttered to Tommy, his voice tight with frustration. At this rate, the war will be over before we get anywhere. My grandmother moves faster and she’s got arthritis. Tommy snickered nervously. Maybe that’s his plan. Stall until the Germans surrender out of boredom. Even some of the quieter soldiers, like Eddie Walsh, a 20-year-old farmer’s son from Kansas, started to shift nervously.

Walsh had been raised to respect the land and those who understood it. But even he was beginning to wonder if Joe was being overly cautious, seeing threats that didn’t exist. Then Joe stopped abruptly. He held up a closed fist, the universal signal for halt. The platoon froze instantly, training overriding frustration. Joe knelt down slowly and pressed his hand flat against the muddy ground. He stayed like that for nearly a full minute, eyes closed, completely still, looking for all the world like he was praying or meditating.

Tommy couldn’t help himself, the nervous energy and fear bubbling over. Is he praying? Should we join hands and form a circle? Maybe sing a hymn. Russo stifled a laugh, but it came out as a snort. Dalton hissed sharply. Shut it, Henderson. Now Joe stood up slowly, his movements deliberate and controlled. He turned to face the sergeant, his expression grave. There are men ahead. Close. Maybe 200 yd, possibly less. Dalton frowned, scanning the fog shrouded forest. How do you know?

I don’t hear anything. Joe pointed at the ground, then gestured at the trees around them. No birds, no insects, no small animals moving through the underbrush. Something scared them off and recently. The air smells different, too. Gun oil, cigarette smoke, very faint, but it’s there. Dalton looked around, straining his senses. He didn’t hear anything unusual. He didn’t see anything suspicious. He didn’t smell anything but wet earth and rotting leaves, but Joe’s expression was dead serious, and there was absolute certainty in his voice.

Dalton made the call. trusting his scout despite his doubts. We’ll move around them. Wide arc to the east. Keep our distance. Joe shook his head immediately. East is worse. There’s a ridgeel line about 300 yd that direction. If they’re dug in properly, if they have observers up high, they’ll see us coming from half a mile away. We’ll be exposed on the approach. Dalton’s jaw tightened, frustration and stress evident in every line of his face. Then what do you suggest?

We can’t sit here all day. Joe pointed west toward terrain that looked even more difficult. Through the thicker trees, the ground is rougher. The cover is better. Slower, yes, but safer. Much safer. Dalton exhaled hard, the breath misting in the cold air. He didn’t like it. Every instinct trained into him at Fort Benning said to take the high ground, to use speed and aggression, to push forward. But Joe had been right about the trail. And something in the scouts voice made him pause.

Fine, lead the way, but stay sharp. The platoon adjusted course, moving into terrain so dense it felt claustrophobic. As they pushed through the underbrush, Murphy noticed something that made him respect Joe even more. The Apache scout had taken off his boots and tied them to his pack. He was walking barefoot through the cold mud, his feet moving silently over roots and stones that would have made noise under boots. Murphy understood immediately. Joe was listening with his whole body, not just his ears.

He was feeling vibrations through the ground, sensing changes in terrain that boots would mask. It was something Murphy’s grandfather had told him about once, how the old hunters could feel a deer’s approach through their feet. He had thought it was just a story. Now he was watching it happen. An hour later, they heard voices, German voices speaking in low tones that carried through the fog. The platoon dropped low instantly, hearts hammering, adrenaline spiking. Through the mist, they could make out the shapes of enemy soldiers, maybe a dozen of them, setting up a machine gun nest with interlocking fields of fire exactly where Dalton had wanted to go.

The position was well concealed, professionally constructed, with ammunition boxes stacked and ready. If the platoon had stayed on the original path, if they had taken the eastern route, they would have walked straight into a killing zone. The machine gun would have cut them down before they could find cover. Dalton’s face went pale as he realized how close they had come to disaster. He looked at Joe with new eyes, seeing not a primitive tracker, but a soldier who had just saved every life in the platoon.

Not a word. He mouthed silently. They backed away slowly, carefully, every man holding his breath. It took 20 minutes to put enough distance between themselves and the German position to feel relatively safe. When they were far enough away, Dalton grabbed Joe by the shoulder, his grip tight with emotion. You just saved our lives, all of us. We’d be dead right now if we’d gone east. Joe nodded once, his expression unchanged. That’s the job, Sergeant. That’s why I’m here.

Dalton held his gaze for a long moment, then released him. From now on, we go where you say, when you say. No questions, no arguments. Joe allowed himself the smallest hint of a smile. Appreciated, Sergeant, but questions are fine. I’d rather you understand why we’re doing something than just follow blindly. Dalton actually laughed, a short bark of surprised respect. Fair enough. The men were noticeably quieter after that incident. Tommy stopped making jokes, his usual nervous pattering up.

Russo stopped rolling his eyes whenever Joe suggested a course change. Even Crawford looked at Joe with something approaching awe, realizing that his West Point education had significant gaps. Eddie Walsh, who had been quietly observant throughout, approached Joe during their next rest break. My father taught me to watch the weather, to read the animals, to respect the land. I should have known better than to doubt you. I’m sorry. Joe looked at the young farmer with understanding. Your father sounds like a wise man.

Hold on to what he taught you. It’ll keep you alive. Walsh nodded gratefully. But the real test, the moment that would define everything, came on the third day. They were moving through a narrow valley, trees pressing in on both sides when Joe suddenly stopped. This time he didn’t kneel to check the ground. He didn’t examine tracks or test the wind. He just stood there perfectly still, every muscle tensed, staring into the woods ahead with an intensity that was almost frightening.

Dalton moved up beside him, rifle ready. What is it? What do you see? Joe’s voice was barely a whisper. So quiet Dalton had to lean in to hear. We’re being watched right now. Someone has eyes on us. The men tensed immediately, fingers moving to triggers, safeties clicking off. Eyes scanned the treeine desperately, looking for any sign of movement, any hint of the enemy. But there was nothing visible. No movement, no sound, no muzzle flash or glint of metal.

Just the endless gray fog and the steady dripping of rain from the branches overhead. The silence stretched out, becoming oppressive. Russo spoke up, frustration and fear bleeding into his voice. There’s nothing there, Sarge. I don’t see anything. We’re wasting time standing here like targets. Tommy, emboldened by the apparent emptiness of the forest, muttered loud enough to be heard. Maybe the spirits are playing tricks on him. Maybe he’s seeing things that aren’t there. A few nervous laughs rippled through the group, born more from tension than genuine humor.

Dalton looked at Joe, searching his face for any sign of doubt or uncertainty. Are you absolutely sure? Joe didn’t move, didn’t blink, his eyes still locked on a specific section of forest. I’m sure, Sergeant. Someone is out there watching us, waiting. Probably a forward observer. If we keep moving, if we make noise, he’ll call down artillery or signal an ambush. We need to stop now. But the men were done waiting. They had been cold, wet, and terrified for 3 days.

They had followed this Apache tracker through mud and rain, taking longer roots and moving at a crawl. And now they were being asked to stand still in the open because of a feeling, an instinct, something they couldn’t see or verify. The tension that had been building finally reached a breaking point. Russo took a step forward, his voice rising. I’m not dying in this forest because some tracker thinks he sees ghosts. There’s nothing out there. We need to move.

Others began to shift restlessly, fingers tightening on their triggers, ready to push forward regardless of Joe’s warning. The discipline was fracturing. Fear and frustration overriding training. Crawford tried to intervene. Hold your positions. That’s an order. But even his authority was wavering. And that’s when Audi Murphy stepped in. He moved between Joe and the rest of the platoon. His rifle held low, but his presence commanding. His voice when he spoke was firm and carried an authority that had nothing to do with rank.

Lower your rifles now. The men hesitated, caught off guard. Murphy’s eyes swept over them, cold and hard as flint. If he says there’s something out there, then there’s something out there. I grew up tracking game to keep my family from starving. I spent years in the woods learning to read signs most people never see. I know what it looks like when a man reads the land properly. Joe isn’t guessing. He’s not seeing ghosts or talking to spirits.

He’s seeing what you’re too loud, too modern, too arrogant to notice. Now lower your rifles, shut your mouths, and stay quiet. If you don’t trust him, trust me. The authority in his voice was undeniable, backed by weeks of proven courage under fire. One by one, the men obeyed, lowering their weapons and falling silent. Murphy turned to Joe, his voice dropping to a whisper. “Where? Exactly where?” Joe pointed with minimal movement, barely extending his arm. “30 yards, left side of that fallen log, low to the ground, probably prone.

He’s been there for at least 5 minutes, maybe longer.” Murphy squinted into the fog, using every skill his grandfather had taught him. For a long moment, there was nothing, just trees and mist and shadows. Then barely visible through the gray, a shape that didn’t quite match the surrounding terrain. A slight irregularity in the pattern of leaves and branches, a German scout lying flat in the underbrush with a radio on his back, watching them through binoculars. He had been waiting for them to bunch up, to make noise, to give away their exact position so he could call in coordinates for artillery or signal an ambush team.

If the platoon had pushed forward, if they had ignored Joe’s warning and walked into the valley, they would have been slaughtered. Artillery would have rained down on them, or machine guns would have opened up from concealed positions. None of them would have made it out alive. Murphy raised his rifle slowly, sighting carefully through the fog. He controlled his breathing, let out half a breath, and squeezed the trigger gently. The shot cracked through the forest impossibly loud. After the tense silence, the German scout jerked once, his body going rigid, then collapsed and went still.

Immediately, the platoon spread out in a practice drill, taking cover behind trees, scanning for additional threats. But there was only the one scout. He had been alone, a forward observer doing his job, and now he was dead. The forest fell silent again, but it was a different silence now. The watching presence was gone. Dalton moved up beside Murphy and Joe, his face grim with the realization of how close they had come. How the hell did you know he was there?

I’ve been fighting for 3 years and I didn’t see anything. Joe looked at him calmly. The birds stopped singing about 5 minutes ago. Not gradually, but all at once, like something scared them. The air smells different when someone’s been in one place too long. Sweat, gun oil, the chemicals in uniforms, and the way the fog was moving. There was something blocking the natural flow. A shape that shouldn’t be there. Dalton shook his head in disbelief. You saw all that?

You read all that from birds and fog? Joe nodded simply. It’s what I was trained to do. Murphy clapped him once on the shoulder, a gesture of respect between equals. You saved us. Every single one of us. Joe met his eyes. We save each other. That’s how this works. The men didn’t laugh after that. The joke stopped completely. When they made camp that night, the atmosphere had changed fundamentally. Tommy Henderson approached Joe quietly, his cocky Brooklyn attitude replaced by genuine humility.

I’m sorry for the jokes, for the disrespect, for not listening. You’re a better soldier than I’ll ever be. Joe looked at him for a long moment, then nodded. You’re young. You’ll learn. The important thing is that you’re willing to learn. Tommy swallowed hard. If we make it out of this war, I’m going to tell everyone about you, about what you did. Joe smiled slightly. Just tell them to listen to respect knowledge that comes from different places. That’s enough.

Russo came over too, offering Joe his canteen. You earned this and my apology. I was wrong about you. Dead wrong. Joe took the canteen, drank deeply, and handed it back. Apology accepted. We’re good. Eddie Walsh sat down beside them. I grew up on a farm. My father taught me to watch the weather, the animals, the land. He said, “Nature would tell you everything you needed to know if you paid attention. I should have recognized what you were doing from the start.” Joe allowed himself a genuine smile.

Your father was a wise man. The old knowledge isn’t primitive. It’s just different. Both ways of knowing have value. Lieutenant Crawford pulled Joe aside before they moved out the next morning. His West Point bearing was still there, but it was tempered now with hard-earned wisdom. I was taught a lot of things at the academy. Tactics, strategy, logistics, combined arms operations, but they didn’t teach me how to listen to the forest, how to read the land the way you do.

I’m glad you’re with us. I’m glad the army had the sense to recruit soldiers like you. Joe met his eyes steadily. Respect goes both ways, sir. You’re a good officer. You listen when it matters. Crawford nodded, genuinely moved. It does go both ways. And you have mine completely. Sergeant Dalton gathered the platoon before they headed back to base. His voice was serious, carrying the weight of command and hard experience. Listen up. What happened out here stays with us, but I want every one of you to remember this for the rest of your lives.

We almost died because we didn’t listen. Because we thought we knew better. Because we dismissed knowledge that didn’t fit into our narrow view of how things should work. Joe Tall Mountain saved this platoon. Not with a rifle, not with a grenade, not with any of the tools we’ve been trained to use. He saved us with knowledge we didn’t have and skills we didn’t respect. If you ever serve with a native scout again, if you ever meet someone whose knowledge comes from a different tradition, you shut your mouth and you listen.

You learn. You respect. Understood? The men responded in unison, and this time they meant it. Yes, Sergeant. When they returned to base, word spread quickly through the division. The story of the Apache tracker who saw a German scout through fog and instinct, who saved an entire platoon from walking into an ambush, became legend. Other platoon specifically requested native scouts. Officers who had dismissed them as gimmicks or publicity stunts started paying serious attention, incorporating traditional tracking methods into their operations.

Joe Tall Mountain continued to serve throughout the war, leading dozens of patrols through some of the most dangerous terrain in Europe. He guided men through the Kmar pocket, through the Seagreed line, and eventually into Germany itself. He never lost a man under his watch. Not a single one. His record was perfect, and his reputation grew with every successful mission. Audi Murphy went on to become the most decorated American soldier of World War II, earning the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, Two Silver Stars, the Legion of Merit, and every other combat award the United States could give.

He became famous, a national hero whose face appeared on magazine covers and movie posters. But he never forgot the lesson he learned in the Vojes forest. In interviews after the war, Murphy often spoke about the importance of respecting different kinds of knowledge, different ways of seeing the world. He credited soldiers like Joe Tall Mountain with teaching him that courage wasn’t just about charging into battle with guns blazing. It was about listening when others spoke, learning when others taught, and trusting the people who had skills you didn’t possess.

He said that the bravest thing he ever did wasn’t earning the Medal of Honor. It was standing between his platoon and a man they were ready to ignore and telling them to trust someone they didn’t understand. The men of that platoon carried the memory of those three days for the rest of their lives. It became a defining moment, a before and after that shaped who they became. Tommy Henderson survived the war and returned to Brooklyn. He became a teacher working in the same rough neighborhood where he had grown up.

He told his students about the time he almost got his entire unit killed because he thought he knew better than someone who had spent a lifetime learning to read the land. He taught them about respect, about humility, about the danger of dismissing knowledge that comes from unfamiliar sources. His students remembered those lessons long after they forgot algebra and history dates. Mike Russo went home to Boston and worked construction, building the city back up after the depression and the war.

He kept a photograph of the platoon on his desk at the union hall. And whenever someone asked about it, he pointed to Joe Tall Mountain. That man saved my life. I didn’t deserve it. I mocked him, disrespected him, doubted him, but he did his job anyway. He kept me alive when I would have walked straight into death. I owe him everything. Russo spent his later years working with Native American advocacy groups, trying in his small way to repay a debt he felt he could never fully settle.

Eddie Walsh returned to his family farm in Kansas. He married his childhood sweetheart, raised four children, and taught them to watch the animals, to listen to the wind, to respect the signs that nature gave them. He told them it wasn’t superstition or primitive thinking. It was survival. It was wisdom passed down through generations. It was knowledge that had kept humans alive for thousands of years before cities and technology. His children grew up with a deep respect for the land and for people whose knowledge came from sources other than books.

Frank Dalton retired as a decorated sergeant and spent his later years advocating for Native American veterans, many of whom returned home to find they were still treated as secondclass citizens despite their service and sacrifice. He testified before Congress about the contributions of native scouts and code talkers, insisting that their skills had saved countless American lives. He fought for benefits, for recognition, for the respect these men had earned in blood. He made it his mission to ensure that soldiers like Joe Tall Mountain were remembered and honored.

Lieutenant Thaddius Crawford became a career officer and eventually rose to the rank of colonel. He rewrote parts of the Army’s reconnaissance training manual to include traditional tracking methods, citing the lessons he learned from soldiers like Joe Tall Mountain. He brought Native American veterans to West Point to lecture cadetses, ensuring that the next generation of officers understood that knowledge comes in many forms. His reforms saved lives in Korea, in Vietnam, and in every conflict that followed. Joe himself rarely spoke about the war.

Like many Native American veterans, he returned home to a country that didn’t always honor his service. He went back to Arizona to the reservation where he had grown up, and he lived quietly. He worked as a hunting guide, taught tracking to young people, and tried to preserve the old ways that were slowly disappearing. But those who served with him never forgot. They wrote letters. They visited when they could. They made sure his story was told, even when he was reluctant to tell it himself.

In 1982, Joe Tall Mountain passed away at the age of 62 in Arizona. His funeral was attended by over 300 people, including a dozen men from his old platoon. They came from across the country, old men now with gray hair and grandchildren. But they came. Tommy Henderson gave the eulogy. He stood at the podium, now an old man himself with trembling hands, and said through tears, “I was a stupid kid who thought I knew everything.” Joe Tall Mountain taught me that wisdom doesn’t come from books or classrooms or even from experience alone.

It comes from listening, from respecting the knowledge of others, from understanding that there are a thousand ways to see the world and none of them are invalid. He saved my life. He saved all of our lives, and I will be grateful to him until the day I die. When they lowered Joe’s casket into the ground, 12 old soldiers stood at attention and saluted. It was the least they could do. Audi Murphy died in a plane crash in 1971 just a few miles from the Vosge Mountains where he had once ordered his men to lower their rifles.

He was 45 years old, still young, still carrying the weight of everything he had seen and done. Among his personal effects was a journal entry from October 1944. It read in Murphy’s neat handwriting. Today I learned that the best soldiers aren’t always the ones who shout the loudest or carry the biggest guns. Sometimes they’re the ones who move quietly, who listen carefully, who see things the rest of us miss. I served with a man like that. His name was Joe Tall Mountain.

He was Apache and he was one of the finest soldiers I ever knew. If I survive this war, I hope I can be half the man he is. The lessons of that day in the Voj forest echoed far beyond the war. In the decades that followed, the US military began to formally recognize the contributions of Native American soldiers. Monuments were built in Washington and across the country. Histories were written. Documentaries were made. The code talkers of the Pacific theater.

The Navajo men who created an unbreakable code based on their language became famous and celebrated. But the trackers, the scouts, the men like Joe Tall Mountain who moved through enemy territory like ghosts often remained unsung. They didn’t seek glory. They didn’t ask for recognition or medals. They did their jobs, saved lives, and went home. Their contributions were quieter, harder to quantify, but no less vital. But for the men who served alongside them, the memory never faded. in reunions held in hotel conference rooms and VFW halls.

In letters exchanged over decades, in late night conversations over drinks when the memories became too heavy to carry alone. They told the same stories about the time a native scout stopped them from walking into an ambush. About the time a tracker found water in a desert where there shouldn’t have been any. About the time an Apache soldier saw a German observer that no one else could see. and a young Texan named Audi Murphy trusted him enough to stop an entire platoon from making a fatal mistake.

These stories were passed down to children and grandchildren, becoming part of family lore, part of the collective memory of what the war had really been like. It’s easy to laugh at what you don’t understand. It’s easy to dismiss knowledge that doesn’t fit into the boxes you’ve been taught, that doesn’t match the curriculum or the manual or the accepted way of doing things. But war has a way of stripping away arrogance, of revealing what actually matters. In the forests of France, in the mountains of Italy, in the jungles of the Pacific, American soldiers learned a hard truth that changed them forever.

Survival didn’t care about pride. It didn’t care about tradition or prejudice or narrow-minded thinking. It cared about results. And the soldiers who brought results, no matter where they came from or how they did it or what color their skin was, were the ones who kept their brothers alive. Joe Tall Mountain was one of those soldiers. He didn’t fight for glory or recognition. He didn’t fight for medals that would gather dust in a drawer. He fought because his country asked him to, even though his people had been pushed onto reservations, stripped of their ancestral land, and treated as outsiders in the nation they called home.

He fought because the men beside him, despite their initial jokes and doubts, were his brothers in arms. And when the moment came, when death was 30 yards away and invisible in the fog, when one wrong move would have killed them all, he did what he had been trained to do since he was a child, learning at his grandfather’s side. He read the signs that others couldn’t see. He trusted his instincts when everyone else doubted, and he saved lives.

The story of the gis who laughed at the Apache tracker is ultimately a story about respect. It’s about the danger of arrogance and the power of humility. It’s about learning to listen, especially when the voice speaking doesn’t sound like yours, doesn’t come from the same background, doesn’t fit your expectations. And it’s about a young soldier from Texas who understood something that too many people forget. The best leaders aren’t the ones who think they have all the answers.

They’re the ones who know when to step back and let someone else lead. who recognize expertise even when it comes in an unfamiliar package. Audi Murphy became a legend not just because he was brave, though he was incredibly brave. He became a legend because he was wise enough to trust the people around him, even when no one else did, especially when no one else did. In the end, the men of that platoon didn’t just survive the Vage forest.

They learned something that stayed with them for the rest of their lives, that shaped how they raised their children and how they moved through the world. They learned that knowledge comes in many forms. That courage means more than charging forward with guns blazing. That sometimes the quietest voice in the room is the one you need to hear the most. Joe Tall Mountain never raised his voice. He never demanded respect or recognition. But he earned it one careful step at a time in a forest where death was always watching and only he could see it coming.

His legacy lived on in the men he saved, in the lessons they learned, in the stories they told. And that in the end is the truest form of immortality.