The General Who Predicted Market Garden’s Failure—and Paid the Price

I. The Man No One Noticed

In a factory in Acton, West London, an old man worked the assembly line.

He arrived on time.

He ate lunch alone.

He spoke English with a thick, unsoftened accent.

His hands—once steady enough to sign orders that sent thousands of men into combat—now trembled slightly as he tightened screws and inspected small electrical components beneath fluorescent lights. The work was repetitive, greasy, anonymous. No one asked questions. No one expected answers.

To his coworkers, he was just another immigrant laborer: poor, quiet, forgettable.

They did not know that the man beside them had once commanded an elite airborne brigade.

They did not know that he had warned the Allies of catastrophe—and been destroyed for being right.

When he died of heart failure in September 1967, they attended the funeral out of courtesy.

Then the priest began to read his military record.

And the room fell silent.

II. A General Without a Country

The name sounded unfamiliar to British ears:

Stanisław Sosabowski

Major General.

Commander, Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade.

Veteran of Warsaw’s defense.

Participant in the largest airborne operation in history.

The man they had known as a factory worker had once been one of Poland’s most capable commanders.

He had also been one of its most inconvenient.

III. September 1944: The Dream of Ending the War

By late summer 1944, the Western Allies were intoxicated by momentum.

France had been liberated. Paris had fallen. German forces appeared to be retreating everywhere. To many senior commanders, the war felt won—it only needed a bold final stroke.

That stroke was Operation Market Garden.

The architect was Bernard Montgomery, who proposed an audacious plan: seize a chain of bridges in the Netherlands using airborne troops, then drive armored columns straight into Germany’s industrial heartland.

If it worked, the war might end by Christmas.

The plan dazzled politicians. It thrilled optimists.

It horrified Sosabowski.

IV. Seven Miles Too Far

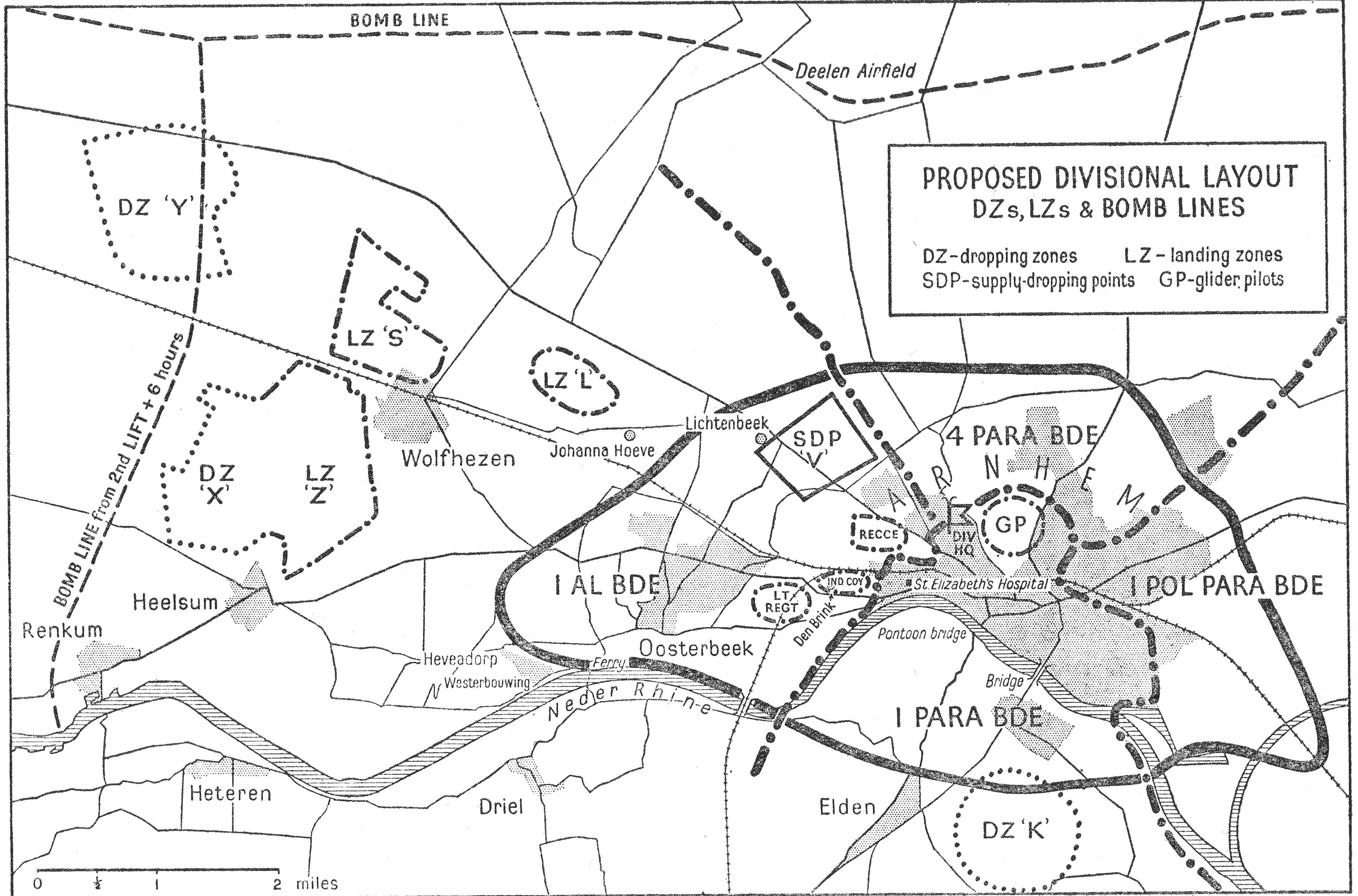

The briefing room in England was crowded with British and Allied officers. Maps were spread across tables. Arrows leapt confidently across rivers and roads.

Sosabowski sat near the back, studying the terrain.

His concern crystallized immediately.

The drop zones for the British 1st Airborne Division were seven miles from the Arnhem bridge—the operation’s most critical objective.

To civilians, seven miles sounded trivial.

To a general, it was an eternity.

Seven miles meant:

No immediate surprise

Time for German reaction

Lightly armed paratroopers marching through hostile territory

Worse still, airborne landings would be spread over three days, due to aircraft shortages. Surprise would not just be reduced—it would be surrendered entirely.

British intelligence insisted resistance would be light.

Sosabowski knew better.

Arnhem was the gateway to Germany. The Germans would defend it savagely.

This was not pessimism.

It was experience.

V. “But the Germans, General…”

When British General Roy Urquhart finished presenting the plan and invited questions, Sosabowski hesitated.

He already knew he was unpopular.

He was foreign.

He spoke accented English.

He had a reputation for bluntness.

Still, when a British officer dismissed German resistance as negligible, Sosabowski could not stay silent.

“But the Germans, General. The Germans.”

The room chilled.

This was more than disagreement—it was a breach of etiquette. A Polish exile telling British commanders that their masterpiece was a death trap.

He explained calmly:

German armor was nearby

Drop zones were too distant

Paratroopers could not hold against tanks

His concerns were waved away.

Lieutenant General Frederick Browning dismissed him as a pessimist. Montgomery believed momentum would overcome obstacles.

Unknown to Sosabowski, intelligence officer Brian Urquhart had photographic evidence of SS Panzer divisions refitting near Arnhem.

That warning was ignored too.

VI. The Disaster Unfolds

On September 17, 1944, Market Garden began.

Everything Sosabowski feared happened—step by step.

Paratroopers landed miles from objectives.

German resistance was immediate and ferocious.

Weather disrupted resupply and reinforcements.

Sosabowski’s Polish brigade was scheduled to jump later, as reinforcement. But on September 19, fog grounded his aircraft.

He waited helplessly as reports confirmed catastrophe.

British airborne forces were surrounded.

The Arnhem bridge was held by a single battalion.

German armor was crushing lightly armed troops.

He had warned them.

Now he could only watch.

VII. The Rhine Ran Red

When Sosabowski finally jumped on September 21, it was into chaos.

Only 950 men—barely a third of his brigade—made the drop near Driel, south of the Rhine. Anti-aircraft fire shredded transport planes. The ferry needed to cross the river had been sunk.

To reach the trapped British, his men had to paddle across the Rhine in rubber boats—under machine-gun fire, at night.

Flares illuminated the river.

German guns opened up.

Sosabowski watched from the bank as the water turned dark with blood.

Only about 200 Poles made it across.

The rest were killed, wounded, or driven back.

Everything he had predicted was happening—paid for with his men’s lives.

VIII. Ordered to Fail Again

Days later, British commanders proposed another night crossing.

Sosabowski studied the plan and felt physically ill.

The crossing point lay directly beneath German positions on high ground. It would be a massacre.

He objected forcefully. Either commit a full division—or evacuate the British airborne forces.

British commanders were done listening.

His brigade would participate.

Orders would be obeyed.

The crossing went ahead.

It was a disaster.

Again.

IX. The Scapegoat Is Chosen

After Market Garden’s failure, blame was inevitable.

Montgomery praised the Poles publicly—then condemned them privately.

In a classified letter to Alan Brooke, Montgomery falsely claimed the Polish brigade had fought poorly and lacked fighting spirit.

It was a lie—contradicted by every report.

But it was politically useful.

At the same time, Winston Churchill was negotiating with Stalin over Poland’s future. Weakening Poland’s military reputation weakened its political leverage.

Sosabowski, the inconvenient truth-teller, became expendable.

British pressure forced the Polish government-in-exile to remove him.

On Christmas 1944, his men learned their commander was dismissed.

They went on hunger strike.

Sosabowski ordered them to stop.

He would not let them suffer for him.

X. Exile After Victory

The war ended.

Sosabowski could not go home.

Communist Poland, controlled by the Soviets, stripped him of citizenship in 1946. Returning officers were imprisoned—or worse.

He became stateless.

He brought his wife and blind son to London. His son had lost his sight serving as a medic during the Warsaw Uprising.

No pension came.

No support followed.

At 57, a major general applied for factory work.

And got it.

XI. The Assembly Line Years

For nearly 20 years, Sosabowski worked at CAV Electrics.

He never spoke of Market Garden.

Never mentioned Montgomery.

Never defended himself.

In 1960, he published his memoirs: Freely I Served. Few noticed.

He worked until age 75.

Then his heart failed.

XII. Vindication—Too Late

History, slowly, corrected itself.

In 2006, the Netherlands awarded the Military Order of William to the Polish brigade. Sosabowski received the Bronze Lion posthumously.

A Dutch documentary exposed the truth British politics had buried.

In 2025—eighty years late—the British government finally paid tribute in Warsaw.

It was not a full apology.

But it was acknowledgment.

Epilogue: A Clean Conscience

Montgomery died famous.

Browning escaped scrutiny.

Sosabowski died poor.

But history belongs not to power—but to truth that survives power.

The old man on the assembly line knew this.

He had been right when being right was unforgivable.

And in the end, that mattered more than statues.