The General Who Vanished in Berlin: How a Nazi Intelligence Chief May Have Been Reborn Inside America’s Secret War

Berlin, April 1945: A City Collapsing, A Man Disappearing

Berlin was not merely losing a war in April 1945—it was unraveling. Smoke choked the streets, artillery thunder rolled through neighborhoods once lined with cafés and theaters, and the stone skeletons of government buildings loomed like tombs. As the Red Army closed in, the city’s final defenders retreated underground, into bunkers and tunnels that smelled of dust, sweat, and despair.

In those final days, countless officials fled, surrendered, or died by their own hand. But one man did something different. He vanished.

His name, according to fragmented records and later intelligence files, was General Wilhelm Kreger—a senior figure in the SS intelligence apparatus, a specialist in psychological warfare, covert logistics, and disinformation. He was not a public face of the Third Reich. He did not deliver speeches or command armies in the open. He worked in shadows, shaping narratives, breaking enemies without firing shots, and erasing traces when operations ended.

On April 30, 1945, as news of Adolf Hitler’s suicide rippled through the bunker complex beneath the Reich Chancellery, witnesses last saw Kreger seated calmly near the communications hub. He reviewed coded documents while others panicked. Then he stood, issued a few quiet instructions, stepped into a side corridor—and was never officially seen again.

No body was recovered. No death confirmed. Berlin did not kill Wilhelm Kreger. It absorbed him.

A Name Quietly Deleted

When Allied forces combed the ruins of Berlin, they expected corpses and captured leaders. Instead, they found gaps—lists of names with no remains, offices stripped with unsettling precision. Soviet investigators, under orders from Joseph Stalin, demanded proof of death for key Nazi figures. Dental records surfaced for some. Graves for others. But for Kreger, there was nothing.

American intelligence initially blamed chaos. Soviet files used a more ominous phrase: possibly exfiltrated.

Eyewitness accounts conflicted wildly. A radio operator claimed Kreger escaped disguised as a medic. Another insisted he was shot near the Tiergarten. Both stories collapsed under scrutiny. Bunker logs—normally meticulous—contained no trace of his name. It was as if someone had reached back through history and erased him.

Then came the whispers. A civilian interpreter near Potsdam reported seeing a German officer matching Kreger’s description boarding an unmarked jeep under American guard days after Berlin fell. The vehicle was not Soviet. Not British. The report was filed, stamped, and buried.

His Dresden apartment told a similar story. It had been searched not by looters, but by professionals. Diaries were gone. Photographs torn from frames. A neighbor recalled an American man asking for “the professor,” a nickname used only by Kreger’s inner circle.

Officially, Wilhelm Kreger was written off as another casualty of the Reich’s collapse. Unofficially, intelligence agencies on both sides of the emerging Cold War kept his name alive.

The Lists No One Was Meant to See

As Europe smoldered, a new conflict began—not for territory, but for knowledge. The Soviet NKVD and American intelligence compiled secret lists of men who had disappeared before the war ended. These were not decorated generals or public criminals. They were specialists: rocket engineers, codebreakers, chemical experts, and intelligence tacticians.

Near the top of both lists was Wilhelm Kreger.

The Soviets labeled him “extremely valuable,” citing expertise in psychological manipulation and deep-field operations. American files took a stranger turn. His name appeared intermittently in intercepts in 1946 and 1947. Then, in 1948, it vanished—not from the world, but from paperwork.

That same year, a declassified CIA index listed “Strategic Assets Secured.” Most names were known scientists recruited under Operation Paperclip. One entry, however, was fully redacted, marked “Tier One, Exempt from Prosecution.”

It fueled a suspicion long whispered in intelligence circles: the most dangerous Nazis were not sent to court. They were sent west.

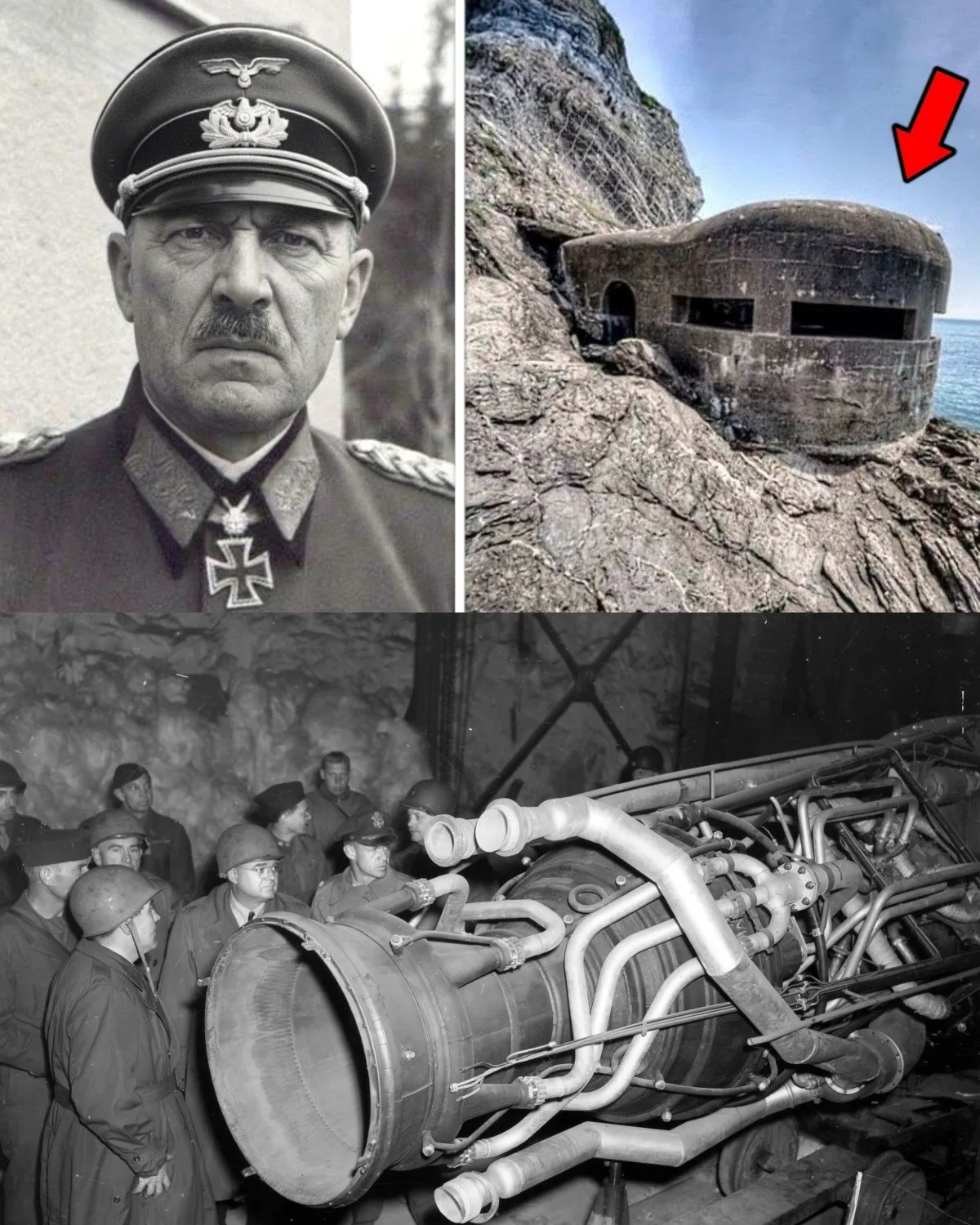

Operation Paperclip: Science, Shadows, and Moral Compromise

Publicly, the United States championed denazification. Privately, it feared Soviet superiority. In the summer of 1945, the OSS—predecessor to the CIA—launched Operation Overcast, soon renamed Operation Paperclip. Its mission was blunt: extract Germany’s best minds before Moscow did.

More than 1,600 Germans were recruited. Many were engineers and scientists. Some had overseen weapons programs or human experimentation. Their records were sanitized, their pasts reframed. A paperclip attached to a file meant reinvention.

But Paperclip was not just about rockets and laboratories. It was about leverage.

A handful of recruits were never publicly acknowledged. They did not teach classes or appear in NASA photos. They advised quietly, shaping interrogation doctrine, counterintelligence strategy, and psychological operations. According to later leaks and redacted memos, this was the world Wilhelm Kreger likely entered—not as a celebrity scientist, but as a ghost.

Subject K in the Desert

In 1951, a German national arrived at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico. He carried no identification. His intake file was incomplete, his real name redacted. In internal memos, he was called only “Subject K.”

Subject K did not work with rockets. He did not attend standard briefings. He appeared one day and never left. He lived in government housing, avoided social contact, and was granted unusual access. A junior officer once reported seeing him in a locked archive room at 2:14 a.m., alone, with no key. The report was sealed.

Surveillance logs showed gaps. Doors unlocked without explanation. A quartermaster claimed to see Subject K burning German military documents behind the commissary. His approved transfer request vanished the next day.

In 1957, Subject K was gone. No discharge. No departure record. A single memo noted: “K transferred to alternate site—operational.”

Officially, there was no Subject K.

The Manuscript That Shouldn’t Exist

In 2006, a secondhand bookstore in Hamburg uncovered a slim journal wrapped in wax paper. Inside was a faded stamp: “Eigentum WK”—Property of WK. The handwriting was angular, precise, and partially encoded.

One line stood out: “Der falsche Tod.” The false death.

The manuscript described slipping out of Berlin hours after Hitler’s suicide, guided by foreign handlers. It referenced New Mexico, isolation, and debriefings without pain. The final line chilled translators: “I did not escape. I was collected.”

Handwriting analysis later matched it with high probability to a 1939 military record belonging to Wilhelm Kreger. Days after the manuscript drew attention, it vanished from the bookstore safe. No sign of forced entry. No witnesses.

Paper Trails, False Deaths, and Argentina

A declassified FBI transcript from 1961 added another layer. The subject’s name was fully redacted, but his voice—calm, precise, German-accented—was unmistakable. When asked if he feared prosecution, he replied: “If I were meant to stand trial, I would not be sitting here.”

Later documents hinted at South American placement. In rural Argentina, locals once spoke of “El Coronel,” a German-speaking man who lived quietly, watched constantly, and guarded a reinforced trunk of documents. By the early 1970s, he was gone. No grave. No record.

DNA, Declassification, and a Name Resurfacing

In 2023, a German man tracing his ancestry received a shocking DNA match flagged as a U.S. Department of Defense archival sample from 1979—New Mexico. The genetic link aligned closely with Kreger’s lineage. The Pentagon declined further explanation, citing “Operation Paperclip Strategic Retention.”

Then came a 2024 leak: Cold War files listing “Kreger Wilhelm—Status Operational 1947–1969.” Alias: Kesler F. Final placement: South American theater. A margin note read, chillingly, “Consider disposal.”

A death certificate dated 1951 claimed Kreger died in San Diego. The doctor who signed it was later identified as a former OSS operative known for forged paperwork. The address did not exist.

He had not been buried. He had been erased.

The Meaning of a Vanishing

Wilhelm Kreger did not escape justice. He was absorbed into it—or what passed for it during the Cold War. His story is not unique. Operation Paperclip and related programs reveal a pattern: when enemies became useful, morality bent. Trials were avoided. Names were rewritten.

History forgot Kreger because it was told to. But documents, DNA, and whispers have a way of resurfacing.

The unsettling question is not only where he went, but how many others followed the same path—and what it cost.