The Man Who Wasn’t Supposed to Be There

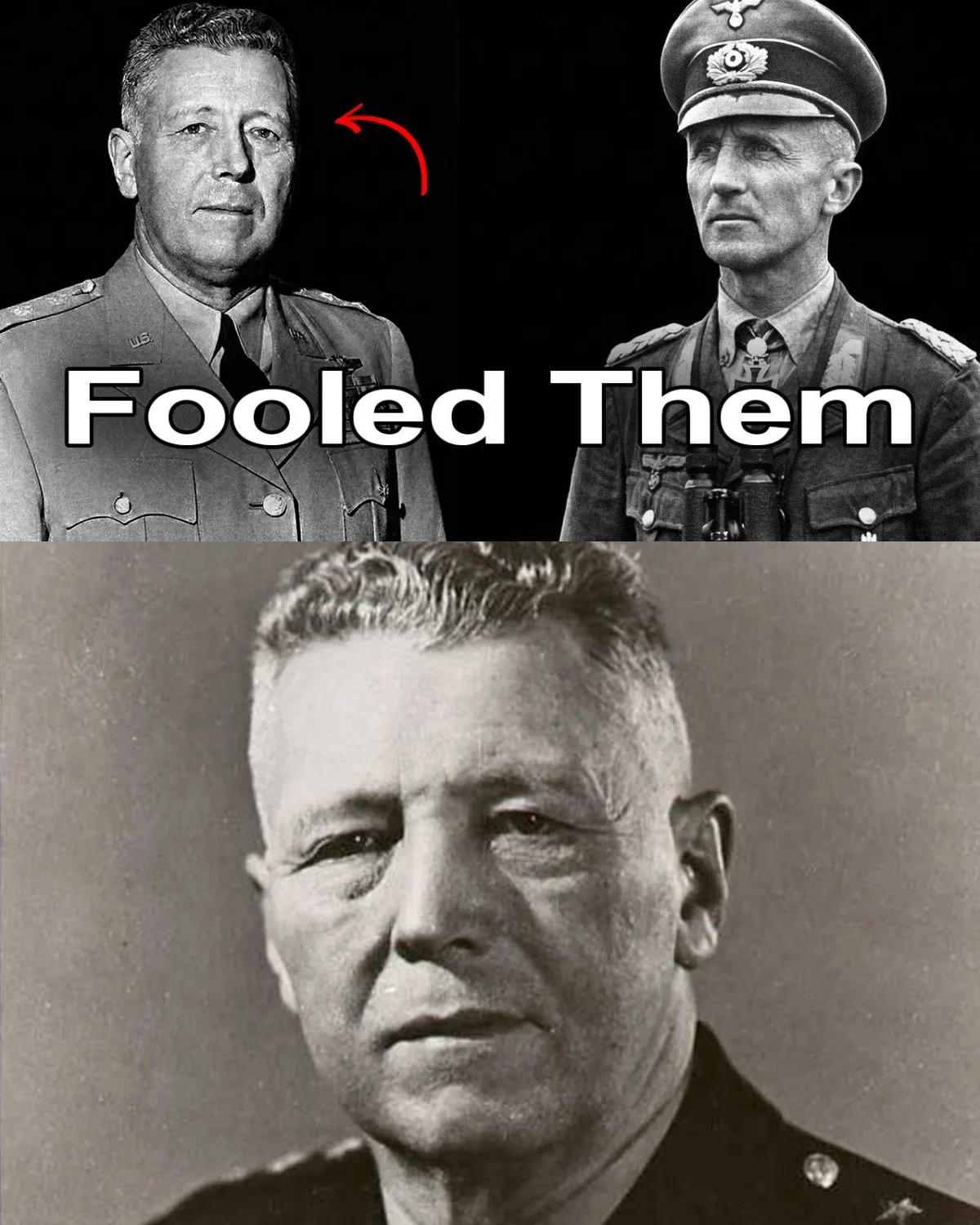

Why German Generals Said an Unknown American Ruined Their Bulge Plan

St. Vith, December 1944 — A Cinematic–Historical Reconstruction

A Jeep in the Snow

On December 17, 1944, a lone jeep rolled into the Belgian town of St. Vith. Snow lay thick on the roads. Refugees clogged the streets. Wounded soldiers moved west in stunned silence.

A brigadier general stepped out.

His name was Bruce C. Clarke.

At that moment, no American newspaper knew who he was. No German intelligence officer had flagged his name. Even most of the soldiers now fighting and dying around St. Vith had never seen him before.

Yet within days, German generals would say—quietly, bitterly, and with disbelief—that this unknown American officer had destroyed their plan for the Battle of the Bulge.

Not delayed it.

Destroyed it.

The German Clock Was Already Ticking

The German offensive—Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein—was built on time.

Hitler’s last gamble in the West depended on speed, surprise, and rigid timetables. Three German armies surged through the Ardennes forest, aiming to split the Allied front, cross the Meuse, and seize Antwerp before Allied logistics and air power could recover.

For Hasso von Manteuffel, commander of the Fifth Panzer Army, one objective mattered above all others in the first 48 hours:

St. Vith.

The town sat astride seven major roads and two rail lines. Every German division pushing west needed those routes. Without St. Vith, the offensive would choke on its own traffic.

Manteuffel’s schedule was precise.

German armor was supposed to be through St. Vith by the evening of December 16.

By the afternoon of December 17, they weren’t.

They were already behind schedule—and now a general they had never heard of was standing in their way with three men and a radio.

An Inheritance of Disaster

Inside the American command post, Major General Alan Jones looked defeated.

His 106th Infantry Division—new, untested, and recently arrived—had been shattered. Two regiments were surrounded on the Schnee Eifel Ridge. Communications were collapsing. German armor was pouring through gaps his infantry could not hold.

Jones told Clarke the truth:

“I’ve thrown in my last chips.”

Clarke had been passing through St. Vith on a routine movement. Instead, he was handed responsibility for the defense of the town.

There were no written orders.

No prepared positions.

No intact front.

His combat command—CCB, 7th Armored Division—about 2,500 men—was still miles away, stuck in traffic jams of retreating soldiers and fleeing civilians.

Clarke walked outside and looked east.

Somewhere in the frozen forest, Manteuffel’s panzer divisions were grinding closer.

Buying Time With Ghosts

Clarke knew two things instantly.

First: the Germans needed St. Vith immediately.

Second: they believed speed would carry them through.

So he did the only thing possible.

He created the illusion of strength.

Before his tanks even arrived, Clarke grabbed every stray unit he could find—engineers, clerks, MPs, headquarters personnel—and placed them on key approach roads. They weren’t meant to stop a panzer army. They were meant to slow it.

Hours mattered.

When CCB finally arrived late on December 17, Clarke made a decision that would define the battle.

He did not dig in.

The Defense That Wasn’t There

A conventional commander would have drawn a solid defensive line east of town and ordered his men to hold.

Clarke refused.

A static line, he knew, would be identified, targeted, and crushed by German artillery and armor. Instead, he revived a method he had perfected months earlier in Lorraine—against the same enemy commander.

Mobile defense.

Small teams of Sherman tanks and armored infantry occupied road junctions, fired, displaced, vanished, and reappeared miles away. They never stayed long enough to be fixed or counted.

German units advancing toward St. Vith ran into tanks—then ran into them again on a different road. Columns were hit from the flank, lost lead vehicles, and stalled.

Reports flooded German headquarters:

“American armor everywhere.”

“Strong resistance on multiple axes.”

“Enemy force strength unclear.”

That uncertainty was fatal.

Fooling an Army

German intelligence officers tried to piece together the picture. What they saw made no sense.

There were gaps everywhere—yet every push met resistance. No continuous American line existed—yet roads remained blocked. Tank contacts appeared, disappeared, and reappeared miles apart.

Their conclusion was exactly what Clarke intended.

They reported that St. Vith was held by a major American armored force—possibly an entire corps.

Manteuffel adjusted his plans.

Instead of bypassing St. Vith, he began preparing a deliberate assault. Divisions meant to drive west toward the Meuse were pulled back and redirected to crack what German staff now called a major defensive position.

Every division diverted was a division not advancing.

The German clock bled minutes… then hours… then days.

Surrounded, Still Holding

On December 19, catastrophe struck.

The two surrounded regiments of the 106th Infantry Division surrendered. Over 7,000 Americans walked into German captivity—the largest mass surrender of U.S. troops in the European Theater.

Clarke’s flanks vanished overnight.

German forces flowed around St. Vith on both sides, pushing west. Clarke was now an island—surrounded on three sides, his supply corridor narrowing by the hour.

Any rational commander would have withdrawn.

Clarke stayed.

He tightened his perimeter, contracting around the road junction itself. He could not hold everything—but he could hold enough.

And the roads remained blocked.

Hitler’s Hammer Falls

By December 20, Hitler knew his timetable was broken—and he was furious.

He released his personal reserve: the Führer Begleit Brigade, an elite armored formation commanded by Colonel Otto Ernst Remer, a fanatical loyalist who had crushed the July 20 plot against Hitler.

This was no longer probing attacks.

This was annihilation.

Artillery barrages intensified. Infantry assaults became coordinated. Clarke’s men fought without sleep in sub-zero temperatures. Ammunition ran low. Casualties mounted with no replacements.

Tank crews fought until their vehicles were knocked out—then fought as infantry. Engineers laid mines, then picked up rifles. Clerks and cooks filled foxholes.

Clarke slept in his jeep.

If his men froze, so would he.

The Goose Egg

On December 21, Clarke made his hardest decision.

He abandoned outer positions and contracted into what headquarters would later call “the fortified goose egg”—an oval-shaped perimeter centered on the western approaches to St. Vith.

It was concentration over coverage.

Inside the goose egg, lines were shorter, gaps fewer, resistance denser. German attacks were blunted yard by yard.

Every hour Clarke held was an hour the Allies used to recover.

To the south, Patton was pivoting the Third Army north.

To the north, Montgomery was stabilizing the line.

At Bastogne, the 101st Airborne was digging in.

None of that would have been possible without time.

Time Clarke was buying with blood.

Breaking Point

On December 22, Manteuffel committed everything.

Infantry, armor, artillery—three axes of attack slammed into the goose egg. German troops penetrated the perimeter. Fighting erupted inside positions that had held for days.

Clarke moved constantly, redirecting what little reserve he had left—stripping quiet sectors to save collapsing ones.

By nightfall, the eastern side of the perimeter was gone.

The junction was about to fall.

Higher command made the call.

Withdraw.

The Perfect Escape

On December 23, Clarke executed what historians would later call one of the finest retrograde operations of the war.

This was not a rout.

This was choreography.

Rear guards simulated a full defensive line while vehicles slipped west one by one. Machine guns fired from empty positions. Mortars dropped rounds from skeleton crews.

German commanders believed the Americans were still there—until they weren’t.

Most of Clarke’s force escaped intact, wounded included.

St. Vith fell seven days after it was supposed to.

Seven days too late.

The German Admission

On Christmas Eve, Manteuffel reported the truth to Hitler’s headquarters.

The offensive was broken.

Years later, in 1965, Clarke met Manteuffel in the United States. Former enemies sat across a table as old men.

Manteuffel told him something astonishing.

German intelligence had believed they were fighting an entire American corps at St. Vith.

Not 2,500 men.

Not two tank companies.

A corps.

Clarke’s mobile defense had fooled the Fifth Panzer Army—and in doing so, ruined the German timetable beyond repair.

The Forgotten Turning Point

History remembers Bastogne.

It remembers “NUTS!”

It remembers Patton’s dash north.

But St. Vith was the main effort.

Without those roads, the German offensive had no future. And one unknown brigadier general—without glory, without press, without memoirs—held them just long enough to break the plan.

Clarke never sought credit.

He never told the story.

The enemy commander did.

And sometimes, that is the most reliable verdict history can offer.