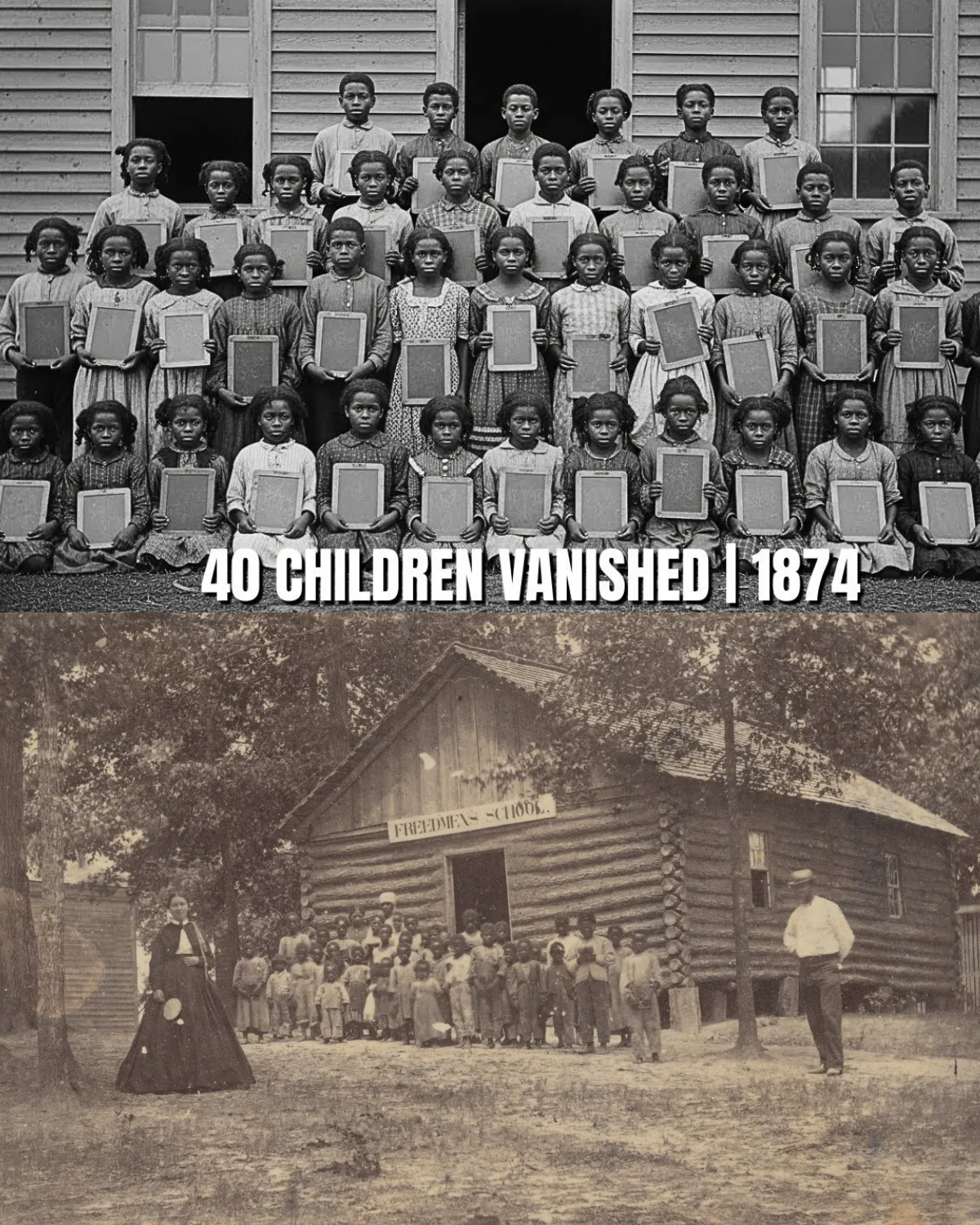

The Night Education Became a Death Sentence: Inside the 1874 School Where 40 Black Children Vanished

At the edge of Willow Creek, Georgia, hidden behind a dense wall of pine trees, stood a building no map acknowledged and no sign marked. To white residents of the town, it was nothing more than an abandoned storage shed, a relic of no importance. To the Black community living in its shadow, it was something far more dangerous—and far more powerful.

It was a school.

On the night of November 14, 1874, forty Black children entered that building for lessons in reading and writing. By sunrise, every one of them was gone. No bodies were recovered. No witnesses testified. No investigation followed. What remained were forty empty benches, slate boards still marked with chalk letters, and a silence so complete it took more than seventy years to break.

This is the story of the school that was never supposed to exist—and the children who vanished because they dared to learn.

Freedom Without Protection

Nine years earlier, the Thirteenth Amendment had formally abolished slavery. But in Georgia, freedom arrived without safety. Sharecropping replaced bondage, trapping families in permanent debt. Convict leasing allowed Black men to be arrested on invented charges and forced back into unpaid labor. Terror organizations like the Ku Klux Klan enforced racial hierarchy through violence while local authorities looked away.

Education was viewed as the most dangerous threat of all.

During slavery, teaching enslaved people to read was illegal, often punished by whipping or death. Literacy meant access to laws, contracts, ideas, and resistance. After emancipation, that fear did not disappear. Instead, it hardened. Schools for Black children were underfunded or outright banned, teachers were threatened, and families were punished for even attempting to educate their children.

In this world, learning to read was not self-improvement. It was defiance.

Clara Montgomery’s Dangerous Gift

Clara Montgomery was born enslaved in 1842 near Savannah. Orphaned young, she grew up serving in a plantation household. By chance—and secrecy—she learned to read when the owner’s daughter quietly shared her lessons with her. When the discovery was made, Clara was punished and sent to the fields. But the knowledge could not be taken back.

After the Civil War, Clara married Samuel Montgomery, a blacksmith who had never learned to read and understood the cost of that deprivation. Together, they saved enough money to buy a small plot of land outside Willow Creek. On it stood a collapsing shed, which Samuel repaired board by board.

In 1868, they made a choice that would cost them everything.

They turned it into a school.

Lessons After Dark

The school operated at night. Children arrived in small groups, slipping through the trees after long days of labor. Clara taught by candlelight using slate boards and chalk. Books were scarce—discarded Bibles and old newspapers salvaged from white households.

She taught reading, arithmetic, and history—the kind that affirmed dignity and possibility. She taught children to count money so they wouldn’t be cheated, to measure land so they would know when they were being lied to, and to write their own names so no one else could erase them.

By 1874, forty students attended. They ranged from six to sixteen years old. Some walked miles in the dark to be there.

Among them was Thomas Reed, ten years old, reading far beyond his age. Sarah Mitchell, twelve, dreamed of becoming a teacher herself. Isaac Johnson, sixteen, worked at a sawmill all day and came anyway so his younger sister Mary could have a future he never had.

For six years, the school survived because it was protected by silence and trust.

Until someone talked.

The Betrayal

Joseph Crawford, a Black groundskeeper with a drinking problem, spoke carelessly one night in a white-owned tavern. The man listening was Robert Whitfield, a former Confederate officer and a leader in the local Ku Klux Klan.

Whitfield understood immediately what the school represented. Education meant independence. Independence meant power. And power threatened everything men like him believed they were entitled to preserve.

But Whitfield did not want martyrs. He wanted erasure.

For weeks, he gathered information. He followed children. Counted them. Watched the school. Then, on November 14, 1874, he acted.

The Night the Children Vanished

The lesson that night focused on writing. The children bent over their slate boards, carefully forming sentences about their dreams.

At 8:45 p.m., Clara heard horses.

The door burst open. Whitfield and armed men filled the room. The children froze. Clara stepped forward, asserting their right to learn. Whitfield laughed.

“These words on paper don’t matter here,” he said.

The children were forced outside. The clearing was ringed with riders—more than twenty men. Whitfield examined the children like livestock. When one of his men questioned killing them, Whitfield explained the plan.

Fire.

An accident.

No witnesses.

When Thomas Reed stepped forward and declared that knowledge could not be killed, Whitfield struck him to the ground.

The children were driven back inside. The door was barred. Kerosene was poured around the walls.

Inside, Clara retrieved her journal from beneath the floorboards. She had documented every child—names, dreams, progress. She clutched it to her chest as smoke filled the room.

The fire was lit.

By morning, the building was ash.

The Official Lie

Two days later, the local newspaper reported a tragic accident involving an abandoned shed. No investigation was planned. The Black community knew the truth but could not speak it without risking their lives.

Joseph Crawford was found dead days later, officially ruled a suicide.

For seventy-three years, the story survived only through whispered memory.

What the Fire Couldn’t Destroy

In 1947, a construction crew uncovered a buried metal box beneath the old foundation. Inside was Clara Montgomery’s journal, preserved in oilcloth.

It listed every child by name. It described the school. It described the night of the fire.

Historians later confirmed the account through death records, land deeds, and private correspondence. The man responsible, Robert Whitfield, had lived a long life without consequence.

In the 1990s, the story finally reached national attention. In 2004, Georgia issued a formal apology and erected a memorial listing the names of all forty children, Clara, and Samuel.

Clara’s journal is now housed at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, preserved so the world cannot pretend this never happened.

Why This Story Still Matters

The children of Willow Creek were murdered because education threatened power. That truth has not disappeared. Their story reminds us that access to education was not freely given—it was fought for, bled for, and stolen at terrible cost.

The men who burned that school believed they were ending something.

They were wrong.

The children vanished, but their names survived. Their knowledge survived. And their descendants live in a world shaped by the courage they were killed for.

Knowledge cannot be burned away.

And history, no matter how long it is buried, remembers.