The Perfect Wedding Photo—Until the Groom’s Hand Revealed a Threat No One Was Meant to See

The photograph arrived on an unremarkable gray morning in October 2019, wrapped in brown paper and tied with careful twine. At first glance, it was everything a wedding portrait from the early twentieth century was supposed to be: formal, elegant, reassuring. A bride in white. A groom standing proudly at her side. A moment of promise frozen in sepia.

And yet, by the time experts finished examining it, the image would be reclassified—not as a family keepsake, but as evidence.

This was not a love story preserved on photographic paper.

It was a warning, hidden in plain sight for more than a century.

A Photograph That Should Have Been Claimed—but Never Was

The image was delivered to a photographic restoration archive in Portland, Oregon, where senior restorer Sarah Chen specialized in rescuing damaged historical photographs. She had handled thousands of images spanning decades, from Civil War-era portraits to Edwardian studio weddings. Experience had trained her eye to notice what others overlooked.

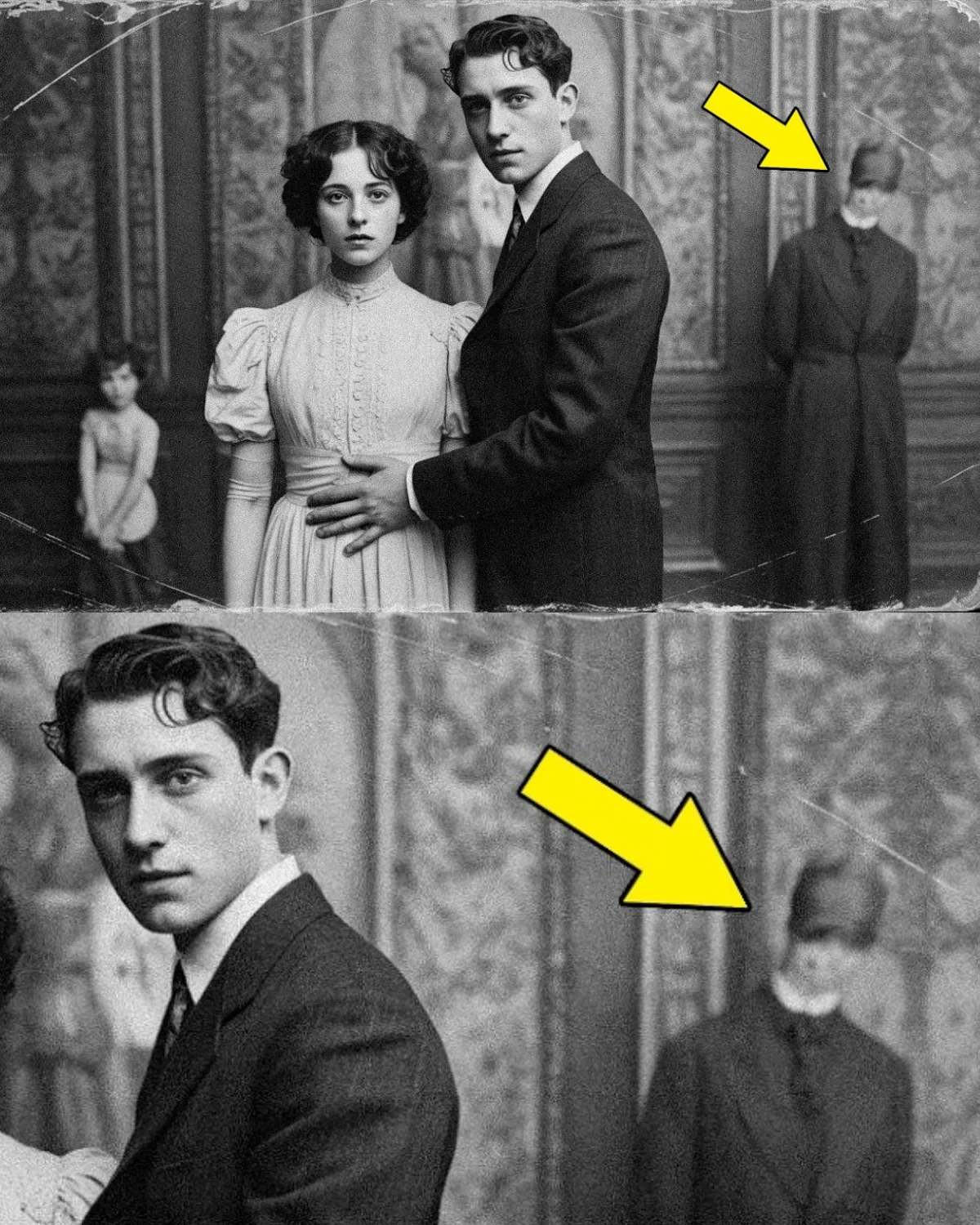

The wedding photograph dated from 1906. The bride wore a high-collared lace gown with exaggerated sleeves, her dark hair styled in the fashionable Gibson Girl look of the era. The groom stood close, impeccably dressed, his mustache carefully groomed, his posture confident.

On the back was a studio stamp: Whitmore Photography.

More curious than the image itself was the handwritten note beside the stamp:

Never collected. Payment received in advance. Do not pursue.

In 1906, wedding photographs were prized possessions. Couples waited weeks for them. They were displayed in parlors, sent to relatives, preserved carefully. The idea that a paid-for wedding portrait was never claimed was almost unheard of.

That alone made Sarah pause.

Then she noticed the groom’s hand.

The Detail That Changed Everything

The groom’s right hand rested on the bride’s waist—a common pose meant to signal unity and possession. But something about the positioning was wrong. His fingers were curled unnaturally, pressing inward beneath the fabric. The folds of the bride’s dress did not fall naturally around his grip.

Sarah increased the scan resolution and zoomed in.

Beneath the fabric, a shadow emerged. Small. Metallic. Cylindrical.

Her breath caught.

With further enhancement, the object became unmistakable. The groom was holding a straight razor—pressed against his bride’s side during their wedding photograph.

A weapon concealed in a moment meant to symbolize love.

Names, Dates, and a Disappearance

Using the studio stamp, Sarah contacted the Salem Historical Society. Within days, archivists located a brief wedding announcement in the Salem Evening News from October 1906.

The couple were identified as Thomas Ashford, age 28, and Catherine Rothwell Ashford, age 22, daughter of a respected textile merchant.

But a second clipping, dated three weeks later, told a darker story.

Catherine Ashford Missing. Recently married woman disappears without explanation.

According to the report, Catherine left her home on High Street on November 2, 1906, saying she intended to visit her mother. She never arrived. No witnesses. No body. No explanation.

The case went cold.

Thomas Ashford moved to Boston two years later. He remarried. He lived comfortably. He never spoke publicly about his first wife.

The photograph now took on a new meaning.

A Silent Threat Preserved in Silver

Sarah consulted forensic specialists and a historical psychologist. Their conclusions aligned disturbingly well.

In Edwardian wedding photography, poses were deliberate. For a groom to insist on holding a concealed blade during such a ritualized moment suggested dominance, intimidation, and psychological control. The bride’s posture—leaning subtly away from him, shoulders tense—reinforced the interpretation.

“This isn’t incidental,” one expert concluded. “It’s a message.”

The photographer, it turned out, had noticed something too.

Archival journals from Edmund Crane, the master photographer who trained Whitmore’s staff, contained a chilling entry dated October 1906:

Something troubling about the groom’s demeanor. He insisted on a particular positioning of his hand. Against my better judgment, I complied.

Crane retained the negative against protocol.

When Catherine disappeared weeks later, he showed police the prints—but never mentioned the hidden razor.

Patterns That Should Never Exist—But Did

As word of the discovery spread, archivists across New England began re-examining their collections. What they found was terrifying.

Other wedding photographs from the same era showed similar anomalies. Grooms gripping something metallic beneath fabric. Awkward hand placements. Brides who later died under “accidental” circumstances or vanished entirely.

The pattern extended across Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire.

This was not an isolated case.

The Letter That Confirmed the Truth

The final confirmation came from Catherine’s own family.

A sealed letter written in 1945 by Catherine’s sister, Eleanor Rothwell, described a midnight visit weeks before Catherine vanished. Catherine had shown her bruises. She had described threats. She had spoken of the razor.

Eleanor had gone to the police. She had been dismissed as hysterical. Her father had refused to intervene to avoid scandal.

Two days later, Catherine was gone.

That letter, notarized and witnessed, allowed the Salem Police Department to officially reclassify Catherine’s disappearance as a probable homicide more than a century later.

The Body Beneath the Garden

Using modern ground-penetrating radar, investigators searched properties Thomas Ashford had owned. Beneath what had once been a garden behind the High Street house, they found human remains.

DNA testing confirmed them as Catherine’s.

Knife trauma was evident on the bones.

She was finally laid to rest in her family plot, more than 110 years after her death.

A Photograph That Refused to Stay Silent

Today, Catherine Ashford’s wedding photograph hangs in a permanent exhibit at the Salem Historical Society, accompanied by forensic analysis, diary excerpts, police records, and Eleanor’s letter.

Visitors stand quietly before it.

They look at the groom’s hand.

They look at Catherine’s eyes.

And they understand.

This photograph did not just record a marriage. It recorded a moment of terror, preserved by chance and revealed by patience. It reminds us that history does not always shout its truths.

Sometimes, it whispers them—hidden in the smallest details, waiting for someone willing to look closely enough.