The Village That Refused to Obey: How One Protestant Community Hid 3,000 Jewish Children in Plain Sight

In the winter air of occupied France, fear usually arrived with the sound of boots. In most towns, that sound meant doors slammed shut, curtains drawn, eyes lowered. But in the isolated mountain village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, fear took a different shape. It arrived as a knock on the door in the middle of the night. And almost always, the answer was the same: Come in.

By 1940, Europe was disappearing. Not in the abstract sense of borders shifting or governments collapsing, but in the most literal and terrifying way possible. Jews were vanishing from streets, schools, and homes. Families were broken apart at railway platforms. Children were pulled from their parents’ arms and sent east, their names erased, their futures stolen. The machinery of genocide worked with chilling efficiency.

And then, something impossible happened.

Three thousand Jewish children disappeared from Nazi records. They were not listed among the dead. They were not liberated from camps. They simply ceased to exist in the eyes of the Reich. For decades, historians struggled to explain this anomaly. The answer lay not in forests or bunkers, but in plain sight—inside homes, classrooms, farms, and churches of a small Protestant village that decided obedience had limits.

That village was Le Chambon-sur-Lignon.

Perched high on the windswept Vivarais-Lignon plateau, Le Chambon was poor, cold, and deeply Protestant. Its people were descendants of Huguenots—French Protestants who had endured centuries of persecution, massacres, and exile under Catholic monarchs. Their collective memory was shaped by stories of ancestors hiding in caves, fleeing at night, and choosing conscience over survival. When Jews began knocking on their doors in the early 1940s, the villagers did not see strangers. They saw themselves.

The moral axis of this quiet rebellion began with one man: André Trocmé.

Trocmé was not a soldier. He was not a saboteur. He was a pacifist pastor influenced by Gandhi and Christian nonviolence. Tall, soft-spoken, and unassuming, he believed faith demanded action, not neutrality. In 1942, when the Vichy government ordered pastors to read antisemitic decrees from their pulpits, Trocmé refused. Instead, he told his congregation something radical and dangerous: We must protect the persecuted.

It was not rhetoric. It was instruction.

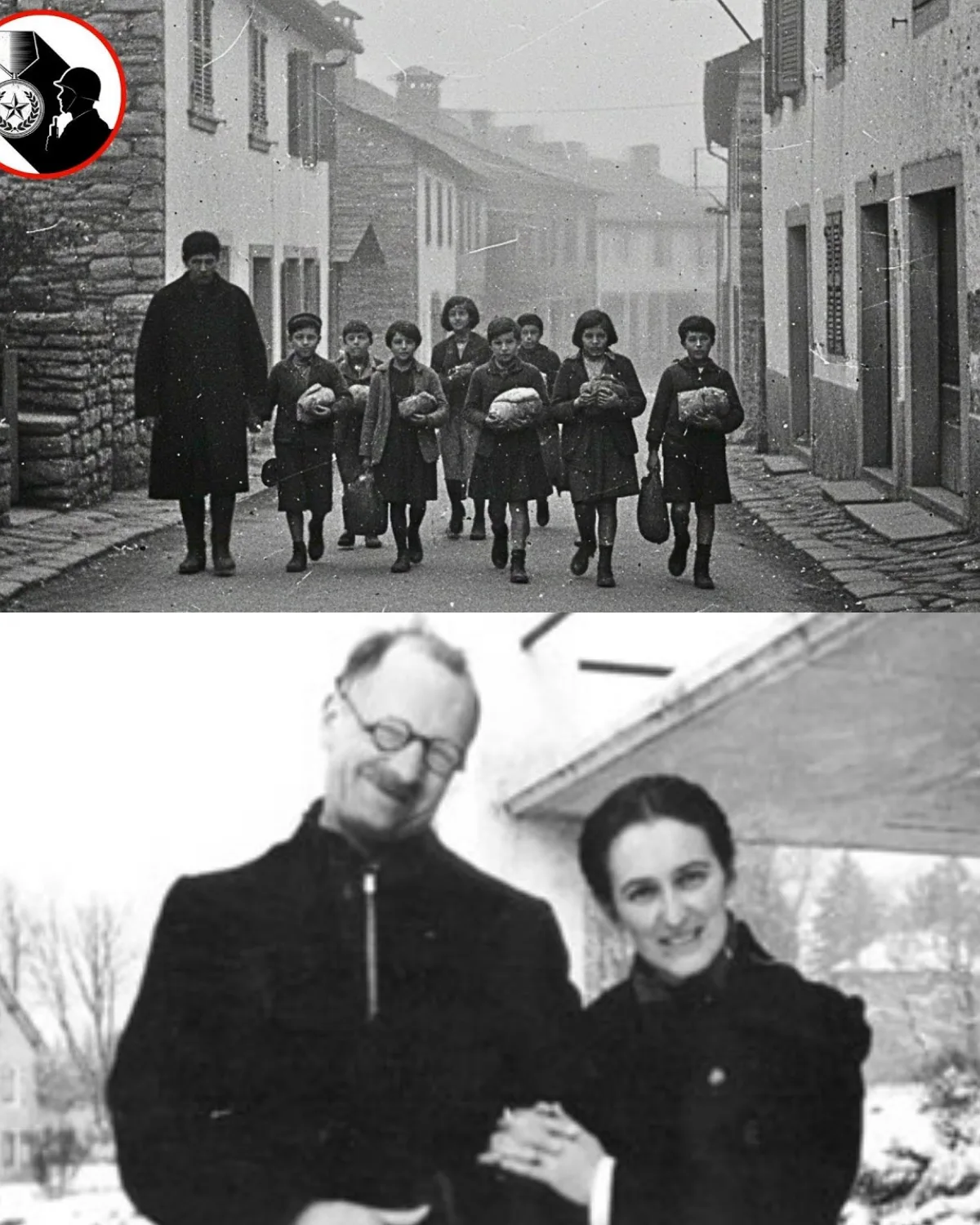

What followed was not an organized resistance cell with codes and weapons. It was something far more threatening to the Nazis—a mass moral conspiracy. Farmers hid children in barns. Teachers forged identities. Housewives stretched meager rations to feed extra mouths. Schoolchildren learned to lie flawlessly to armed men. No one was coerced. Everyone chose.

At Trocmé’s side was his wife, Magda Trocmé, whose quiet courage matched his sermons. Their parsonage became the nerve center of an invisible network. Refugees arrived exhausted and terrified. Magda greeted them with a phrase that survivors remembered decades later: “Naturally, come in.” No hesitation. No questions.

The genius of Le Chambon’s defiance lay in its ordinariness. The children were not hidden underground. They attended school. They played in public squares. They memorized Christian prayers and adopted new names. Teachers knew. Students knew. No one talked. When Gestapo officers searched homes, they found homework on tables and soup on the stove. Everything looked normal. That normality was the camouflage.

The danger was relentless. The village lay in Vichy-controlled territory, crawling with informants and Nazi collaborators. Raids came without warning. Yet time after time, the authorities left empty-handed. When ordered to produce lists of Jews, Trocmé replied, “We do not know what a Jew is. We only know human beings.”

That defiance should have ended in executions. Instead, it spread.

Nearby villages joined. Protestant and Catholic families alike opened their doors. Teenagers guided children across mountain passes into Switzerland. A teenage Jewish refugee became a master forger, producing documents so perfect they fooled Gestapo specialists. Hunger stalked the plateau, but starvation never came. The village refused to let children die.

There were losses. Arrests. Betrayals. The most devastating came in 1944, when Trocmé’s cousin, school headmaster Daniel Trocmé, was deported and murdered in Majdanek after refusing to surrender Jewish students. His final words, recalled by a survivor, were instructions to protect the children.

Even then, the village did not break.

When liberation finally arrived, Le Chambon emerged battered but intact—and surrounded by children with nowhere else to go. Many parents had been murdered in Auschwitz, Treblinka, Sobibor. The villagers did not send the children away. They adopted them. They helped them grieve. They made space for Jewish worship inside Protestant churches. They helped stolen identities heal.

For decades, no one spoke of what happened. France preferred stories of armed resistance. Pacifist villagers who saved lives by lying did not fit the national myth. It took an American filmmaker—one of the saved children—to bring the truth to light in Weapons of the Spirit.

In 1990, Yad Vashem did something unprecedented. It declared the entire village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon Righteous Among the Nations. No other community has ever received that honor.

The villagers rejected sainthood. They insisted they had done nothing special. That insistence may be the most unsettling part of the story.

Because Le Chambon proves something terrifyingly simple: obedience was never the only option.

Three thousand children lived because five thousand villagers decided some lines cannot be crossed. They fired no shots. They destroyed no infrastructure. They simply refused to cooperate with evil. And in doing so, they exposed the lie that genocide succeeds because resistance is impossible.

The knock came to their door. They answered.