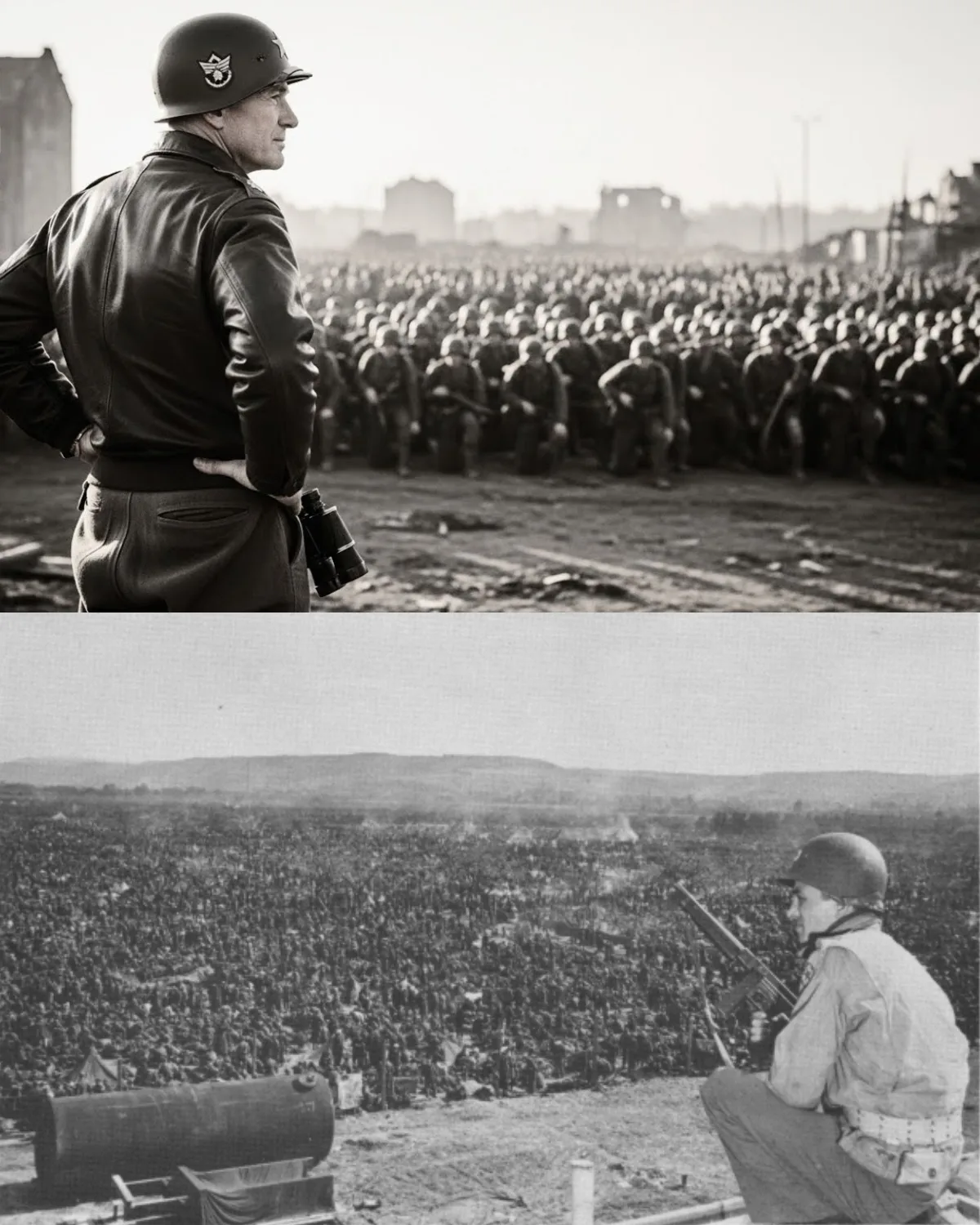

“There Is Nowhere Left to Go”: What the German High Command Said When Patton Captured 300,000 Men in the Ruhr Pocket

On April 1st, 1945, Field Marshal Walter Model stood over a map in his headquarters and understood something Berlin refused to say out loud.

His Army Group B—nearly 300,000 German soldiers—was surrounded in the Ruhr industrial region.

But encirclement was not the real problem.

The real problem was that even if they escaped, there was nowhere left to go.

South of the pocket, George S. Patton had already destroyed every road, river line, and operational concept the German High Command still clung to. Frankfurt had fallen. The Main River had been crossed. Central Germany lay open like a broken door.

The Ruhr Pocket was not a trap.

It was a tomb waiting to be acknowledged.

The Moment the High Command Understood

When Model sent urgent messages to Berlin requesting permission to break out, the responses that came back revealed a leadership no longer operating in reality.

Orders demanded that Army Group B hold its positions.

Tie down the Americans.

Continue resistance.

What those orders did not address was the single question every German staff officer was already asking in silence:

What happens after the breakout?

The answer was devastating.

Patton had not closed the Ruhr Pocket himself—but he had obliterated every meaningful exit. German situation maps showed American columns racing through central Germany, overrunning regions that were supposed to absorb a retreat, refit shattered units, and form new defensive lines.

Those regions no longer existed.

Speed as Strategic Erasure

While Allied planners focused on physically closing the encirclement around the Ruhr, Third Army was doing something more destructive.

It was removing the future.

On March 22nd, Patton’s forces crossed the Rhine at Oppenheim without bombardment, without warning, and without opposition. Within days, multiple corps were east of the river, advancing faster than German command cycles could process.

By March 29th, Frankfurt was in American hands.

By early April, German commanders reviewing maps saw the truth with horrifying clarity:

Even a perfect breakout would emerge into American-controlled territory.

This was not a tactical problem.

It was a strategic nullification.

What Berlin Said—and What It Couldn’t Admit

Communications from the German High Command during the Ruhr crisis reveal a system in collapse.

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, Supreme Commander West, received Model’s requests for realistic withdrawal options. His replies avoided the core issue entirely.

Hold fast.

Maintain discipline.

Conduct local counterattacks.

These orders belonged to a war that no longer existed.

They assumed fuel, mobility, air cover, and operational depth—none of which Germany still possessed. Worse, they assumed time, the one resource Patton had systematically annihilated.

German officers understood the contradiction immediately. Holding the Ruhr served no military purpose if the rest of Germany had already fallen apart.

The Moral Collapse Inside the Pocket

Inside the encirclement, German soldiers were not starving. Ammunition still existed. Command structures remained technically intact.

What had collapsed was belief.

Interrogations of captured officers reveal widespread recognition that the war was lost—not emotionally, but mathematically. There were no reserves. No lines to fall back to. No strategic maneuver left to attempt.

Company commanders faced impossible choices:

Obey orders and sacrifice men for nothing

Disobey orders and be executed for treason

Many quietly chose a third option: surrender when opportunity appeared.

This was not cowardice.

It was clarity.

Walter Model’s Final Decision

Model had built his reputation saving collapsing fronts on the Eastern Front. He understood encirclement doctrine better than almost any German officer alive.

And he knew the Ruhr could not be saved.

By mid-April, American forces were reducing the pocket methodically. Air power dominated the skies. German units surrendered in growing numbers—not because they lacked weapons, but because resistance no longer meant anything.

On April 17th, Model dissolved Army Group B’s headquarters.

He gave subordinate commanders permission to decide for themselves.

Then he walked into a forest near Duisburg and ended his life.

It was not an act of fanaticism.

It was the final acknowledgment that obedience and reality had diverged beyond repair.

The Largest Surrender in the West

By April 18th, organized resistance in the Ruhr Pocket had effectively ceased.

More than 317,000 German soldiers laid down their arms.

Entire corps surrendered intact.

The largest mass surrender to Western Allied forces in the war.

And the German High Command finally understood what Patton’s campaign had done.

They had not been defeated in a single decisive battle.

They had been outpaced out of existence.

What the High Command Finally Admitted

Postwar interrogations and surviving communications reveal the truth German leaders could not say in April 1945:

Even if Army Group B had escaped, it would have emerged into nothing.

No defensive depth.

No operational purpose.

No war left to fight.

Patton’s Third Army had turned encirclement into inevitability—not by tightening the ring, but by destroying everything beyond it.

The Final Lesson of the Ruhr

Encirclement wins battles.

But speed decides wars.

The Ruhr Pocket fell not because its walls were strong, but because escape had been rendered meaningless.

That was the moment the German High Command understood the war was over—not when Berlin fell, not when Hitler died, but when they looked at a map and realized Patton had erased the future itself.

Three hundred thousand men surrendered not because they were surrounded.

They surrendered because there was nothing left worth breaking out to.

On April 1st, 1945, Field Marshal Walter Model stood over a map in his headquarters and understood something Berlin refused to say out loud.

His Army Group B—nearly 300,000 German soldiers—was surrounded in the Ruhr industrial region.

But encirclement was not the real problem.

The real problem was that even if they escaped, there was nowhere left to go.

South of the pocket, George S. Patton had already destroyed every road, river line, and operational concept the German High Command still clung to. Frankfurt had fallen. The Main River had been crossed. Central Germany lay open like a broken door.

The Ruhr Pocket was not a trap.

It was a tomb waiting to be acknowledged.

The Moment the High Command Understood

When Model sent urgent messages to Berlin requesting permission to break out, the responses that came back revealed a leadership no longer operating in reality.

Orders demanded that Army Group B hold its positions.

Tie down the Americans.

Continue resistance.

What those orders did not address was the single question every German staff officer was already asking in silence:

What happens after the breakout?

The answer was devastating.

Patton had not closed the Ruhr Pocket himself—but he had obliterated every meaningful exit. German situation maps showed American columns racing through central Germany, overrunning regions that were supposed to absorb a retreat, refit shattered units, and form new defensive lines.

Those regions no longer existed.

Speed as Strategic Erasure

While Allied planners focused on physically closing the encirclement around the Ruhr, Third Army was doing something more destructive.

It was removing the future.

On March 22nd, Patton’s forces crossed the Rhine at Oppenheim without bombardment, without warning, and without opposition. Within days, multiple corps were east of the river, advancing faster than German command cycles could process.

By March 29th, Frankfurt was in American hands.

By early April, German commanders reviewing maps saw the truth with horrifying clarity:

Even a perfect breakout would emerge into American-controlled territory.

This was not a tactical problem.

It was a strategic nullification.

What Berlin Said—and What It Couldn’t Admit

Communications from the German High Command during the Ruhr crisis reveal a system in collapse.

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, Supreme Commander West, received Model’s requests for realistic withdrawal options. His replies avoided the core issue entirely.

Hold fast.

Maintain discipline.

Conduct local counterattacks.

These orders belonged to a war that no longer existed.

They assumed fuel, mobility, air cover, and operational depth—none of which Germany still possessed. Worse, they assumed time, the one resource Patton had systematically annihilated.

German officers understood the contradiction immediately. Holding the Ruhr served no military purpose if the rest of Germany had already fallen apart.

The Moral Collapse Inside the Pocket

Inside the encirclement, German soldiers were not starving. Ammunition still existed. Command structures remained technically intact.

What had collapsed was belief.

Interrogations of captured officers reveal widespread recognition that the war was lost—not emotionally, but mathematically. There were no reserves. No lines to fall back to. No strategic maneuver left to attempt.

Company commanders faced impossible choices:

Obey orders and sacrifice men for nothing

Disobey orders and be executed for treason

Many quietly chose a third option: surrender when opportunity appeared.

This was not cowardice.

It was clarity.

Walter Model’s Final Decision

Model had built his reputation saving collapsing fronts on the Eastern Front. He understood encirclement doctrine better than almost any German officer alive.

And he knew the Ruhr could not be saved.

By mid-April, American forces were reducing the pocket methodically. Air power dominated the skies. German units surrendered in growing numbers—not because they lacked weapons, but because resistance no longer meant anything.

On April 17th, Model dissolved Army Group B’s headquarters.

He gave subordinate commanders permission to decide for themselves.

Then he walked into a forest near Duisburg and ended his life.

It was not an act of fanaticism.

It was the final acknowledgment that obedience and reality had diverged beyond repair.

The Largest Surrender in the West

By April 18th, organized resistance in the Ruhr Pocket had effectively ceased.

More than 317,000 German soldiers laid down their arms.

Entire corps surrendered intact.

The largest mass surrender to Western Allied forces in the war.

And the German High Command finally understood what Patton’s campaign had done.

They had not been defeated in a single decisive battle.

They had been outpaced out of existence.

What the High Command Finally Admitted

Postwar interrogations and surviving communications reveal the truth German leaders could not say in April 1945:

Even if Army Group B had escaped, it would have emerged into nothing.

No defensive depth.

No operational purpose.

No war left to fight.

Patton’s Third Army had turned encirclement into inevitability—not by tightening the ring, but by destroying everything beyond it.

The Final Lesson of the Ruhr

Encirclement wins battles.

But speed decides wars.

The Ruhr Pocket fell not because its walls were strong, but because escape had been rendered meaningless.

That was the moment the German High Command understood the war was over—not when Berlin fell, not when Hitler died, but when they looked at a map and realized Patton had erased the future itself.

Three hundred thousand men surrendered not because they were surrounded.

They surrendered because there was nothing left worth breaking out to.