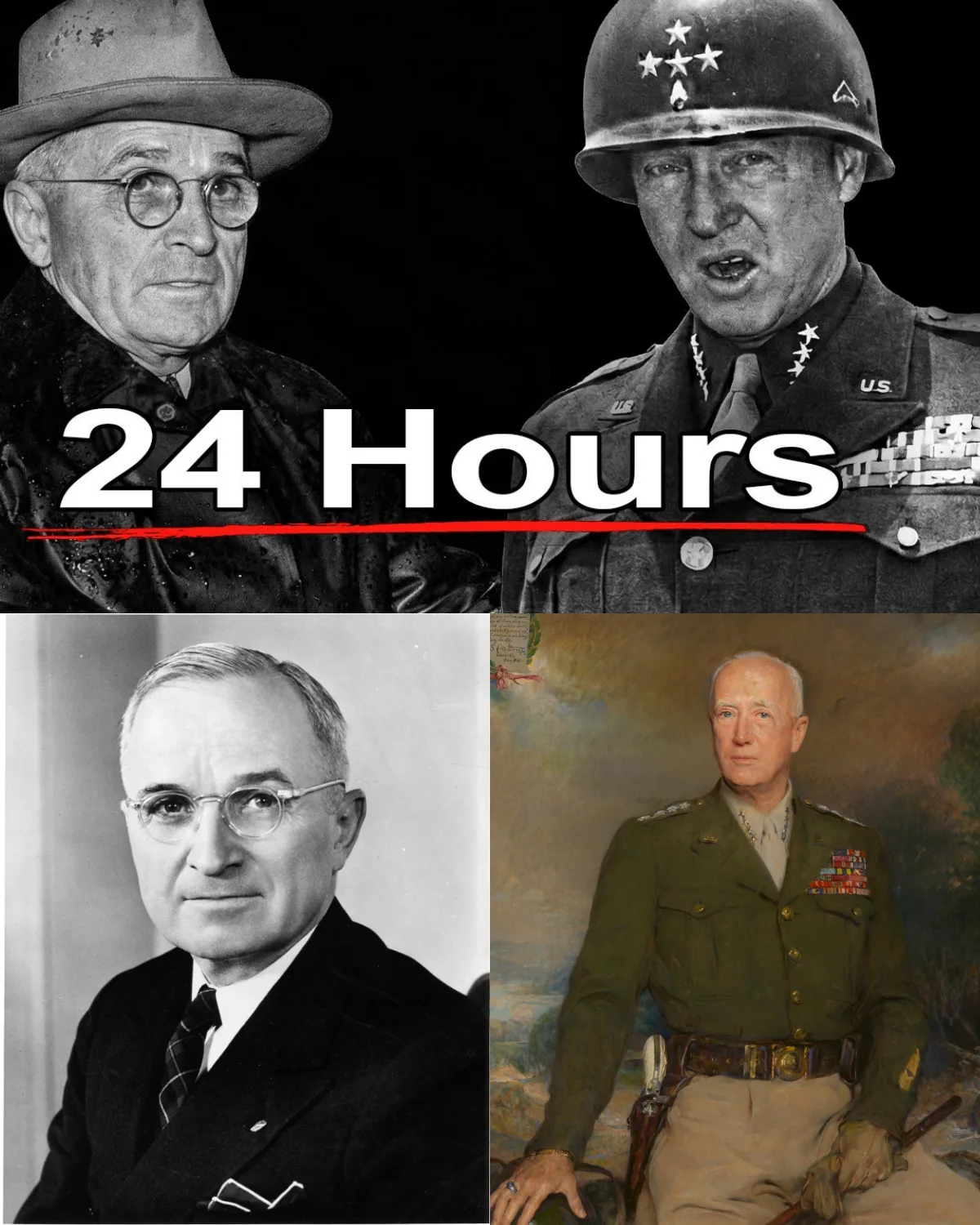

“They Called Him a Glory Hound — Until His Return Threatened to Collapse an Entire Postwar Order: Why a President Feared One General More Than Any Enemy”

In July 1945, long after the guns had fallen silent in Europe, Harry S. Truman sat alone with a pen, a diary, and a problem he could not bomb, negotiate, or ignore.

The problem had a name.

George S. Patton.

Truman did not write about Patton as a commander. He did not assess him as a strategist or a subordinate. He wrote like a man grinding his teeth in private, restraining rage with every sentence. He grouped Patton with men he despised—Custer, MacArthur—calling them glory hounds, reckless, failures.

Failures.

This was the same general who had liberated France at a pace that stunned the world. The same commander whose Third Army had smashed through German lines during the Battle of the Bulge. The same man whose tanks had raced across Europe faster than Allied planners thought possible.

This was not military judgment.

It was fear.

And fear has a way of shaping history far more quietly—and more effectively—than ideology.

I. A President on Unsteady Ground

To understand why Truman feared Patton, you must first understand how fragile Truman himself was in 1945.

He had been president for less than four months. Franklin Roosevelt—the architect of the Allied war effort, the political giant—had died suddenly, leaving behind a shadow too large to escape. Truman stepped into the office like an understudy pushed onto a stage mid-performance.

Washington whispered.

The Democratic establishment saw him as temporary. Republicans sensed weakness. The 1948 election was already looming, and Truman’s hold on power was anything but secure.

Then there was Patton.

Patton was not just a general. He was a symbol.

His face had been on the cover of Time. Newsreels showed him standing in front of advancing tanks, pistols on his hips, barking orders like a figure carved from myth. Millions of Americans did not see Patton as a bureaucrat in uniform—they saw him as the warrior who had won the war.

And people were urging him to run for office.

Columnists floated his name as a presidential candidate. Conservative voices saw him as the antidote to diplomacy with Stalin. A man who would say, plainly and publicly, that half of Europe was being handed over to another tyrant.

In private letters to his wife, Patton discussed influence, history, and destiny.

Truman understood immediately what a Patton campaign would mean.

It would not merely challenge Truman.

It would destroy the legitimacy of everything Truman was trying to build.

II. The Threat Was Not the Man — It Was His Voice

Patton did not need an army to be dangerous.

He needed a microphone.

If Patton came home as a civilian, he could say anything. He could write books. Give speeches. Testify before Congress. Rally veterans. Frame the postwar world not as a victory—but as a betrayal.

He could attack cooperation with Stalin.

He could condemn the Yalta agreements.

He could accuse the White House of sacrificing Eastern Europe for political convenience.

And millions would listen.

Truman could not fire Patton outright. That would turn him into a martyr overnight. The press would explode. Veterans groups would revolt. Republicans would feast.

As long as Patton wore the uniform, however, he could be controlled.

Orders could restrain him.

Assignments could bury him.

Silence could be enforced.

So Truman did something subtle.

He kept Patton in Germany.

III. Exile Without Chains

By October 1945, Patton was stripped of his beloved Third Army command and reassigned to the 15th Army—a ghost formation with no troops, no mission, and no future. Its sole purpose was to write historical reports.

For Patton, this was not an assignment.

It was a padded cell.

The most aggressive, kinetic commander of the war was reduced to paperwork. The roar of engines replaced by the scratching of pens.

Then came the travel bans.

Request after request to return to the United States was denied. Each denial came with a polite bureaucratic excuse. Taken together, they formed a clear pattern.

Patton was being kept away from home.

He understood exactly why.

As long as he remained in Germany, in uniform, he was muzzled.

But Patton was not finished.

IV. The Plan to Break Free

In late November 1945, Patton reached a decision.

He would ask for one final leave. A standard 30-day request. Nothing dramatic. Nothing suspicious.

Once on American soil, he would resign immediately.

Not in Germany—where paperwork could be delayed indefinitely—but in the United States, where resignation would take effect within days.

Then he would speak.

Among Patton’s papers were draft speeches for what he privately called his “truth tour.” They were incendiary.

He planned to tell Americans that the war had been won militarily—and lost politically. That Stalin had never intended to honor his promises. That Soviet atrocities in Eastern Europe were real, documented, and ongoing.

He would argue that the United States had traded one enemy for another—and done so willingly.

This was not policy disagreement.

It was a direct assault on Truman’s legitimacy.

V. The Sudden Yes

In early December 1945, the War Department suddenly approved Patton’s leave.

Thirty days. Beginning December 10.

The reversal was likely tactical. Denying him any longer was raising questions in the press. Better to bring him home and manage him quietly. Pressure him. Persuade him to retire gracefully. Remind him of pensions, legacy, and consequences.

They did not know about the resignation plan.

They did not know about the speeches.

Patton packed his papers on December 9.

He told his staff that by January, he would be free.

He had one day left in Germany.

VI. A Quiet Road Outside Mannheim

On December 9, 1945, Patton went on a hunting trip.

At 11:45 a.m., his staff car traveled along a foggy road near Mannheim. A U.S. Army truck pulled out unexpectedly. The collision was low speed. Almost trivial.

Everyone else walked away.

Patton did not.

He lay paralyzed in the back seat—his neck broken—twenty-four hours before his flight home.

The resignation was never filed.

The speeches were never delivered.

The tour never happened.

Patton lingered for twelve days.

From the White House, there was silence.

No envoy. No visit. Just a cold, formal telegram.

On December 21, 1945, George Patton died.

VII. The Aftermath That Proved Him Right

Within two years, everything Patton had planned to warn America about came true.

Eastern Europe fell behind the Iron Curtain. Communist regimes solidified their grip. The Cold War began.

Truman eventually adopted containment—the very policy Patton had advocated in 1945.

Rebranded. Sanitized. Delayed.

The cost would be forty-five years of tension, proxy wars, and millions of lives.

Patton was buried in Luxembourg, among the men who had followed him across Europe.

Whether his death was an accident remains unproven.

What is proven is simpler—and darker.

Truman got exactly what he needed.

Silence.