They Called Him Brutal and Unforgiving — But in the Ten Days After Kasserine Pass, Patton Destroyed Careers to Save an Army That Had Already Begun to Collapse

On March 6th, 1943, the United States Army was not losing a war.

It was losing faith in itself.

The defeat at Kasserine Pass had done something far worse than cost territory or equipment. It had stripped away the illusion that American soldiers were automatically superior, that industrial power could substitute for experience, that confidence alone could win battles against a hardened enemy.

The German victory had been swift, public, and humiliating. Entire American units had broken. Rifles had been abandoned. Officers had vanished from the front lines. German cameras captured surrendering Americans and broadcast the images across Europe.

The damage was psychological — and contagious.

That was what George S. Patton walked into.

I. The Silence of Defeat

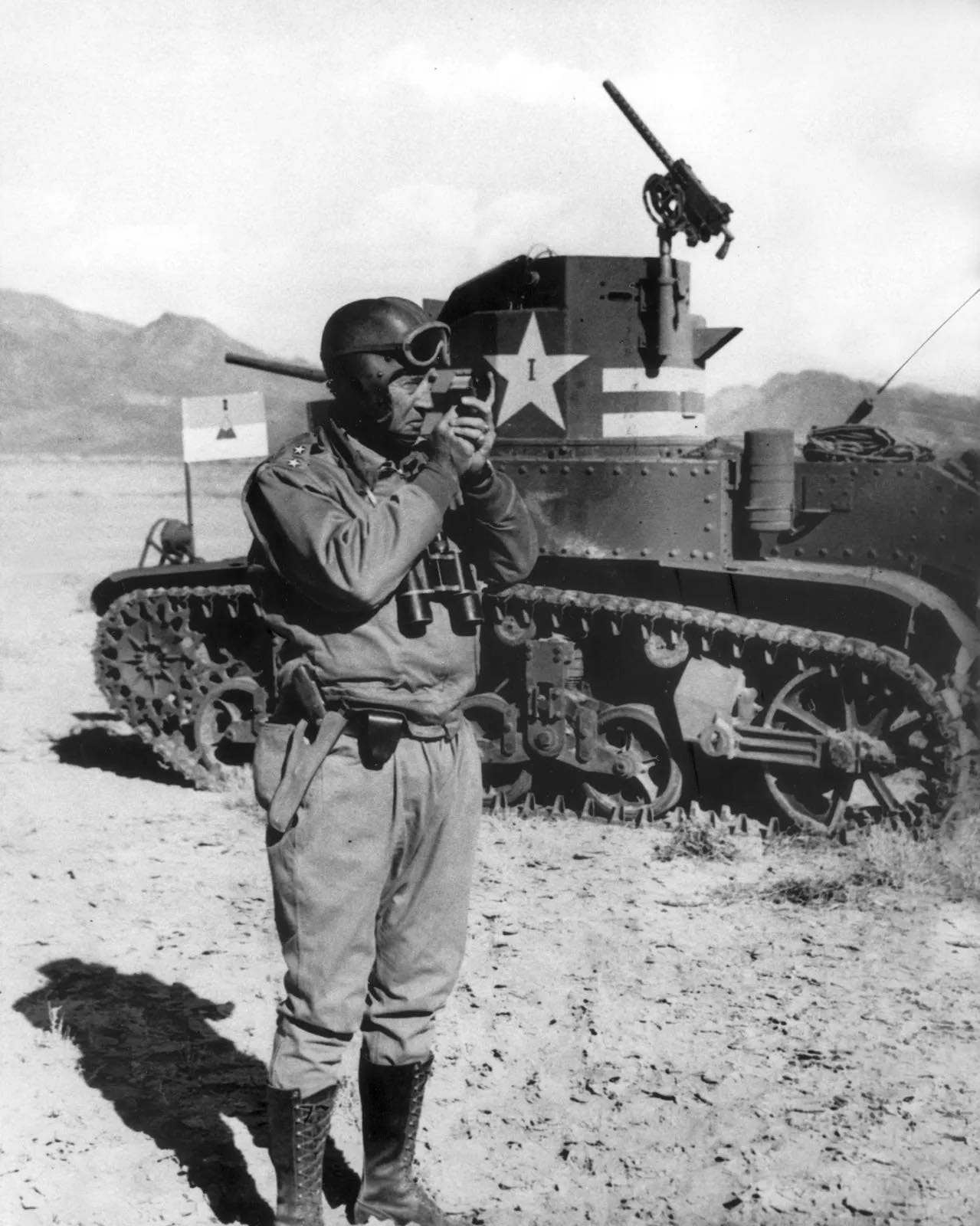

George S. Patton entered the headquarters of the U.S. Second Corps like a verdict.

The building was quiet, but not calm. Officers moved with the stiffness of men who knew something fundamental had gone wrong and feared being named responsible. Conversations stopped when Patton passed. His uniform was immaculate. His helmet polished. His revolvers gleamed.

This was not vanity.

It was theater with intent.

Patton understood something most leaders avoided: after humiliation, men do not need reassurance. They need certainty. And certainty often comes wrapped in fear.

By the end of his first day, officers had already been relieved.

By the end of ten days, Second Corps no longer resembled the force that had collapsed at Kasserine.

That transformation came at a cost few were willing to acknowledge.

II. What Kasserine Really Destroyed

The defeat did not happen because American soldiers were weak.

It happened because they were unprepared — and badly led.

At Kasserine Pass, American forces faced battle-hardened German units commanded by veterans of Poland, France, and the Eastern Front. The Americans had been in North Africa for barely three months. Many officers had never commanded troops under fire.

Leadership failed first.

Second Corps commander Lloyd Fredendall operated from headquarters nearly seventy miles behind the front. Units were scattered, coordination nonexistent. When the German offensive struck, no coherent response followed.

The result was catastrophe.

Over 6,000 casualties.

Hundreds captured.

Entire units routed.

And something worse: the belief, shared even by allies, that Americans could not fight.

Dwight D. Eisenhower understood immediately what was at stake.

This was not a tactical problem.

It was existential.

III. Why Eisenhower Chose Patton

Eisenhower knew Patton’s reputation.

He was difficult. Ruthless. Intolerant of excuses. Known for firing officers without hesitation. A man who believed discipline was not cruelty, but mercy delayed.

And that was exactly why he was sent.

Patton did not believe American soldiers were inferior.

He believed they had been failed.

His mission was simple and impossible: restore order, restore discipline, restore the fighting spirit — fast.

There would be no gentle transition.

IV. The First Firings

Patton’s first order was issued within hours.

Every soldier would wear full combat gear at all times.

No exceptions.

The first officer fired was sitting at a desk without his helmet.

He did not argue. He did not explain. He was simply told to pack his belongings and leave.

Twenty years of service ended in seconds.

The message spread instantly.

This was not symbolic.

This was enforcement.

Officers began wearing helmets indoors. Salutes became rigid. Appearance tightened. Fear moved faster than orders ever could.

But fear was only the beginning.

V. The Front-Line Test

Patton drove forward.

He did not want reports.

He wanted to see.

At the first battalion headquarters, the commander was absent. His executive officer did not know exactly where all companies were positioned.

Patton relieved the commander immediately.

At the next unit, a company commander had placed his command post hundreds of yards behind his forward platoons. He explained it was for communications.

Patton removed him on the spot.

A commander, Patton believed, belongs where his men are dying.

Over the next days, Patton moved relentlessly from position to position, asking questions officers should have been able to answer in their sleep.

Many could not.

They were fired.

Not because they lacked courage — but because they lacked readiness.

VI. Terror as a Teaching Tool

The effect was electric.

Every Jeep engine caused officers to stiffen. Every inspection felt like judgment. Careers balanced on answers given under pressure.

Some officers hated Patton.

Others understood him immediately.

The enlisted men noticed something new: leadership was finally being held accountable.

Failure was no longer abstract.

It had consequences.

VII. Rebuilding How the Army Thought

Patton did not stop at purges.

He changed how the army fought.

Defensive tank tactics were abandoned. Tanks would maneuver, exploit, and attack aggressively. Artillery coordination became immediate. Infantry and armor trained together daily.

But the most important change was psychological.

American soldiers stopped seeing themselves as victims of German superiority.

They began seeing themselves as predators again.

Patton’s speeches were profane, absolute, and unapologetic. He did not comfort. He commanded belief.

Confidence returned — not because defeat was denied, but because it had been punished.

VIII. The Test at El Guettar

El Guettar

Eleven days after taking command, Patton launched an offensive.

The same soldiers who had fled at Kasserine attacked at dawn.

They advanced six miles by noon.

When German armor counterattacked days later, the Americans did not break.

Artillery responded instantly. Anti-tank guns held. Infantry stayed in position.

The Germans were stopped cold.

Over thirty tanks destroyed.

The psychological wound of Kasserine finally began to close.

IX. The Price No One Talks About

Patton’s methods worked.

That is not debated.

What is debated is the cost.

Dozens of officers lost their careers — some deservedly, others simply unsuited for frontline command. Good administrators, loyal servants, men who had never been taught how to fight modern war.

They left quietly.

No trials. No headlines.

Just a lifetime of wondering what might have been.

Patton did not distinguish.

Combat command required aggression.

Those who could not provide it were removed.

X. The Aftertaste

Second Corps went on to fight successfully through Tunisia, Sicily, and Italy.

Patton would become legendary.

The officers he promoted became generals.

The officers he fired vanished from history.

This is the uncomfortable truth: the army survived because it chose effectiveness over fairness.

Patton saved the army by breaking it first.

He sacrificed careers so others would not have to sacrifice lives.

And that is why his ten days after Kasserine remain one of the darkest, most necessary transformations in American military history.

Leadership failed once.

Patton made sure it would never fail the same way again.