They Called His Engine Swap “Illegal” — Until His P-51 Outran Every Jet at 490 MPH

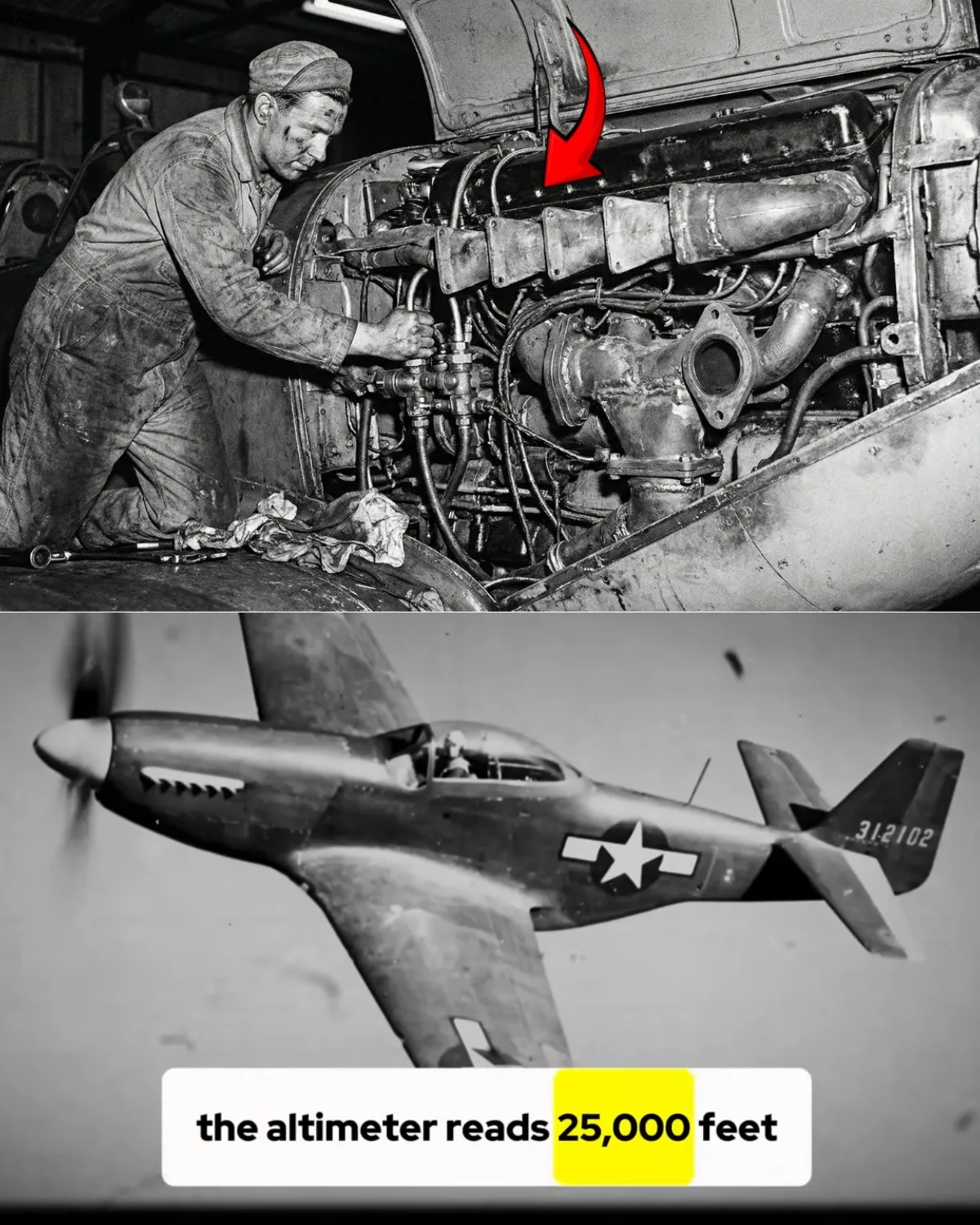

The altimeter needle trembled as it passed 25,000 feet.

The year was 1945.

The place was the cold, thin air over a collapsing Germany—where oxygen thinned, metal strained, and the future of aerial warfare was being decided in seconds rather than years.

Major James Brooks eased the throttle of his P-51 Mustang forward—past the red line, past every safety margin drilled into him since flight school. The manifold pressure spiked. The engine screamed in protest. This was not the Mustang pilots knew from bomber escort duty. This aircraft was stripped, lightened, sharpened into something predatory.

Ahead of him, cutting a black scar through the pale sky, was the future itself: a Messerschmitt Me 262.

The jet pilot knew the numbers. Every German pilot did. Jets flew at speeds no piston engine aircraft could match. The laws of physics had already chosen sides—or so Berlin believed. He pushed his throttles forward, confident that history, science, and Hitler’s promises were all on his side.

He was wrong.

Brooks flipped the switch for water–methanol injection.

The Mustang lunged forward as if kicked by a giant. The airspeed needle swept past 450… 460… 480 miles per hour. The impossible was unfolding in real time. The propeller plane was not falling behind—it was closing. Hunter and hunted reversed roles in seconds.

At 490 mph, Brooks squeezed the trigger. Six .50-caliber machine guns stitched fire across the jet’s engine nacelles. The Me 262 disintegrated in a blossom of flame and debris, its wreckage spiraling toward the ruins below.

A propeller fighter had just outrun—and killed—a jet.

This moment should never have existed. Engineers said the airframe would tear itself apart. Generals said the modifications were reckless, unnecessary, and possibly illegal. The laws of aerodynamics said “no.”

History said otherwise.

The Fighter Nobody Wanted

To understand how a piston-engine aircraft reached into the jet age and pulled it back down, we must rewind to a moment of Allied desperation.

In 1942, Europe was burning. The Royal Air Force clung to survival, and American air power was about to enter the war under a dangerous illusion. The doctrine of the “self-defending bomber” held that heavily armed bombers flying in tight formations could protect themselves. Fighters were considered optional.

That theory died over Germany.

The Eighth Air Force launched daylight bombing raids into occupied Europe and was slaughtered. German fighters attacked head-on, exploiting blind spots. Entire bomber groups vanished in a single afternoon. Loss rates suggested total annihilation within months.

What the bombers needed was a long-range escort—something that could fly to Berlin and back. The existing fighters could not do it. The P-47 Thunderbolt drank fuel like a battleship. The P-38 Lightning suffered mechanical issues at altitude.

And sitting awkwardly in this crisis was the Mustang.

Originally rejected by the United States Army Air Forces, the Mustang was fast at low altitude but crippled above 15,000 feet. Its Allison engine simply could not breathe in thin air. At bomber escort altitudes, it was defenseless.

The airframe, however, was nearly perfect.

That contradiction caught the attention of a British test pilot named Ronnie Harker.

The Heresy of the Merlin

Harker flew the Mustang and immediately saw the problem. Below 15,000 feet, it handled like a dream. Above that, it suffocated. He knew exactly why. The Allison V-1710 had a single-stage supercharger—adequate for ground support, useless in the stratosphere.

Harker also knew the solution.

The Rolls-Royce Merlin was already proving itself in the Supermarine Spitfire. Its two-stage, two-speed supercharger allowed it to maintain power above 30,000 feet. It was a masterpiece born from the Battle of Britain.

The idea was obvious. The consequences were not.

Swapping a British engine into an American fighter violated procurement rules, national pride, and bureaucratic orthodoxy. American officials bristled at the implication that a British engine was superior. British officials doubted the conversion was even possible.

Harker ignored them all.

In a small hangar at Hucknall, engineers tore into a Mustang airframe. Mounts were redesigned. Cooling systems rebuilt. Supercharger ducting was forced into spaces never meant to hold it. The project was unofficial, underfunded, and quietly tolerated rather than approved.

It took six weeks.

On October 13, 1942, the prototype—nicknamed Mustang X—took to the air.

At 30,000 feet, it reached 440 mph, faster than anything in the Allied inventory.

The heresy worked.

Detroit Saves the Sky

There was only one problem: Rolls-Royce could not build enough engines.

The solution came from an unlikely source—the Packard Motor Car Company in Detroit. Accustomed to luxury automobiles, Packard was asked to mass-produce one of the most complex aircraft engines ever built.

They did not merely copy the Merlin. They improved it.

Packard engineers redrew every blueprint, tightened tolerances to automotive standards, and transformed a hand-built masterpiece into an industrial weapon. The result was the Packard Merlin V-1650, more reliable and consistent than its British counterpart.

Now the pieces aligned.

The P-51B Mustang entered service in late 1943.

German pilots saw them over Berlin.

Hermann Göring reportedly understood the implication instantly: if American fighters could escort bombers to the heart of the Reich, the war was lost.

The Jet Shock

Just as the Mustang began to dominate, Germany unveiled its last gamble—the Me 262. Faster than anything with a propeller, armed with devastating cannons, it seemed to restore German technological superiority overnight.

The standard P-51D could not catch it.

So engineers returned to the drawing board.

They stripped weight from the airframe, removed anything nonessential, redesigned structural components, and installed the ultimate evolution of the Merlin—the Packard V-1650-9, capable of sustaining extreme manifold pressures with water–methanol injection.

The result was the P-51H Mustang.

Lighter. Faster. More dangerous.

In level flight, it reached 487 mph. In a dive, it brushed the edge of compressibility. It climbed at 5,000 feet per minute.

For a brief window in 1945, it could chase jets.

The Moment Physics Blinked

When Major Brooks chased down the Me 262, he was flying the absolute limit of piston-engine technology. Every bolt was stressed. Every vibration threatened catastrophe. The aircraft was unforgiving—but unstoppable in the hands of a skilled pilot.

This was not doctrine.

This was not bureaucracy.

This was desperation weaponized into brilliance.

Only 555 P-51Hs were built. The war ended before they could change strategy—but not before they changed history.

The jet age arrived. The propeller became obsolete.

But the Mustang went out on top.

Legacy of the “Illegal” Idea

The engine swap that “should not have worked” reshaped air warfare. It destroyed the Luftwaffe, protected the bombers, and accelerated the collapse of Nazi Germany. It proved that doctrine without adaptability is suicide, and that innovation often begins as disobedience.

When a P-51 Mustang roars across an airshow sky today, it is not just nostalgia. It is the sound of rules being broken, of engineers refusing “good enough,” of pilots pushing past fear and red lines alike.

For one impossible moment in 1945, a propeller fighter chased the future—and caught it.

If you want:

Part II expanding this to a full 4,000–4,500 words

A YouTube documentary script version

Or a shorter cinematic narration cut

Just tell me.