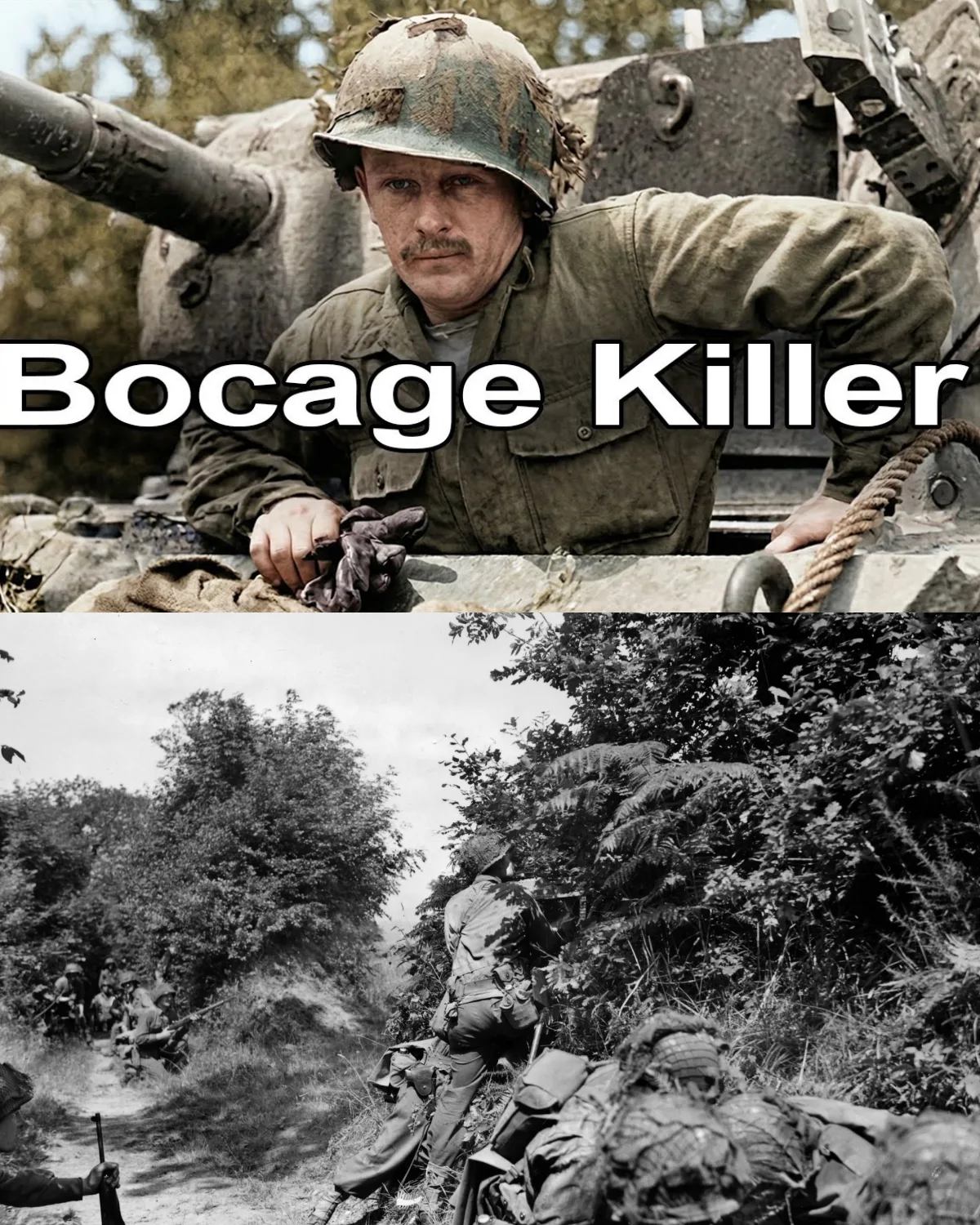

“They Died Belly-Up in the Hedges — Until a Sergeant Turned Rommel’s Steel Into Fangs: How One Small Idea Shattered a Thousand-Year Defense and Unleashed the Breakout of France”

On July 3rd, 1944, a Sherman tank did exactly what it had been trained to do.

It climbed.

The engine roared. The tracks bit into the earth. The nose rose up the Norman hedgerow like a practiced maneuver drilled on clean training grounds thousands of miles away. For a moment, the tank looked triumphant—perched on top of the ancient embankment, steel cresting soil.

Then the belly cleared the hedge.

A German anti-tank gun fired once.

White light. Metal tearing. Silence.

Four Americans died in three seconds.

The Sherman slumped forward, burning, its wreckage blocking the narrow path behind it. Its gun had never fired a shot. Its armor—the thick plates everyone trusted—had never mattered. The kill had come from below, through the thinnest steel on the vehicle, exposed exactly as German gunners expected.

That scene was not exceptional.

It was routine.

Across Normandy, American tanks were being destroyed not by brilliance, not by daring maneuvers—but by terrain the army had never prepared to fight in.

I. The Green Labyrinth

Everyone remembered the Atlantic Wall.

The bunkers.

The obstacles.

The mines.

Those were visible defenses—concrete and steel meant to stop the invasion at the waterline. But once the Allies pushed inland, they encountered something far older, far more patient, and far more lethal.

The Norman bocage.

A living fortress grown over a thousand years.

Each hedgerow was an earthen wall four to six feet high, topped with dense vegetation and anchored by roots so thick that artillery shells barely disturbed them. They divided the countryside into thousands of small fields, each one a natural strongpoint.

No sightlines.

No maneuver space.

No horizon.

Every field was a box.

Every hedge was a wall.

German commanders immediately understood what this meant. They didn’t need to build defenses. Normandy itself was the defense.

American doctrine said tanks went over obstacles.

In the bocage, that doctrine was a death sentence.

II. Tanks That Couldn’t Fight

When a Sherman climbed a hedgerow, it tilted backward at a steep angle. For five to ten seconds—an eternity in combat—the tank was helpless.

Its main gun pointed uselessly at the sky.

Its thin belly armor faced the enemy.

German 75mm guns, 88s, StuG assault guns, and Panzerfaust teams waited patiently. One shot was enough. The Sherman’s belly armor was barely an inch thick in places. Sometimes less.

One shot. One kill.

The Germans turned American tanks into targets on a firing range.

Without armor support, American infantry paid the price.

They cleared the hedges the old way—field by field, hedge by hedge. German machine guns were pre-sited. Mortars were pre-registered. Every gap was covered.

An American platoon could fight all day for a single field.

Then they would stare at the next hedge.

And begin again.

Casualty rates in some divisions exceeded fifty percent. Replacement soldiers arrived and died on the same day. For the men on the ground, the war shrank to two hundred yards of mud and the next wall of roots.

The horizon did not exist.

III. When Generals Had No Answer

By late June, Omar Bradley, commander of First Army, faced a nightmare.

The advance had stalled. Losses were unsustainable. Resources were being poured into the bocage with almost nothing to show for it.

Staff officers proposed solutions.

More artillery.

Special engineer units.

British flamethrower tanks.

None of it worked at scale.

The hedgerows swallowed men, machines, and time.

The solution did not come from a planning room.

It came from a sergeant.

IV. The Man Who Watched His Friends Die

Sergeant Curtis G. Culin Jr. served with the 102nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron.

He wasn’t an engineer.

He wasn’t a designer.

He wasn’t trying to change doctrine.

He was trying to stop watching tanks die belly-up in front of him.

Culin asked a simple question no manual had considered:

What if tanks didn’t go over the hedgerows?

What if they went through them?

His idea was crude, brutal, and perfect.

Weld steel teeth to the front of the tank. Let them bite into the base of the hedge. Let the tank push straight through instead of climbing.

His officers listened.

Then came the real problem.

Steel.

V. Rommel’s Steel, Reborn

The beaches of Normandy were littered with it.

German beach obstacles—hedgehogs, I-beams, twisted steel crosses—installed on Erwin Rommel’s orders to rip open landing craft.

Tons of high-quality steel, sitting useless now that the invasion had succeeded.

Someone made the connection.

The steel meant to stop the Allies could be used to free them.

It was poetic.

It was practical.

And it worked.

American units set up makeshift factories on the beaches. Welders cut apart German obstacles and reshaped them into crude but deadly tank attachments—four or five steel prongs welded to a plate bolted onto the Sherman’s front hull.

They angled downward like tusks.

When a tank hit a hedge, the teeth dug in. The weight of thirty-three tons did the rest.

The hedgerow broke.

Soldiers called them Rhino tanks.

VI. Silence Before the Storm

Within days, the modification spread rapidly. But Bradley made a crucial decision.

The Germans could not know.

If they learned that American tanks could now punch through hedgerows, they would adapt. They would change tactics. They would reposition guns.

So the Rhino tanks stayed hidden.

Infantry kept dying in the hedges.

Bradley was waiting for Operation Cobra.

VII. Cobra

On July 25th, 1944, over 1,500 heavy bombers struck German positions near Saint-Lô. The bombing was chaotic. Some bombs fell short. Americans died. Among them was Lesley McNair, the highest-ranking American officer killed in the European theater.

Then the ground attack went in.

This time, the tanks had teeth.

On July 26th, Rhino tanks drove straight at the hedgerows.

They didn’t climb.

They didn’t hesitate.

They hit at speed.

Roots snapped. Earth collapsed. Hedges that had held armies for centuries disintegrated under steel tusks and engine torque.

German units waiting for the familiar routine—tanks cresting, bellies exposed—found themselves flanked, surrounded, erased.

In two days, American forces advanced farther than in the previous month.

The bocage broke.

VIII. The Flood

On August 1st, George S. Patton’s Third Army went operational.

The hedgerows were no longer a prison.

They were an obstacle already defeated.

Patton’s armor poured into open country—the terrain American tanks were built for. For the first time in weeks, soldiers saw horizons instead of walls.

In one month, Third Army advanced over four hundred miles.

France fell open.

German forces collapsed. Over fifty thousand were killed or captured in August alone. The Falaise Pocket destroyed much of the German Seventh Army.

The bocage had held for six weeks.

Then it broke in six days.

IX. Aftertaste

Sergeant Curtis Culin received the Legion of Merit.

His invention went from idea to mass production in two weeks—not because of genius alone, but because American military culture allowed it.

An enlisted man spoke.

Officers listened.

Steel was welded.

Men lived.

Rommel had tried to stop the invasion with steel.

A sergeant used that same steel to end the stalemate.

That is how wars really turn—not always with speeches or strategies, but with small ideas born where men are dying.

And sometimes, the thing that defeats an empire is a welding torch and the refusal to accept that this is “just how it is.”