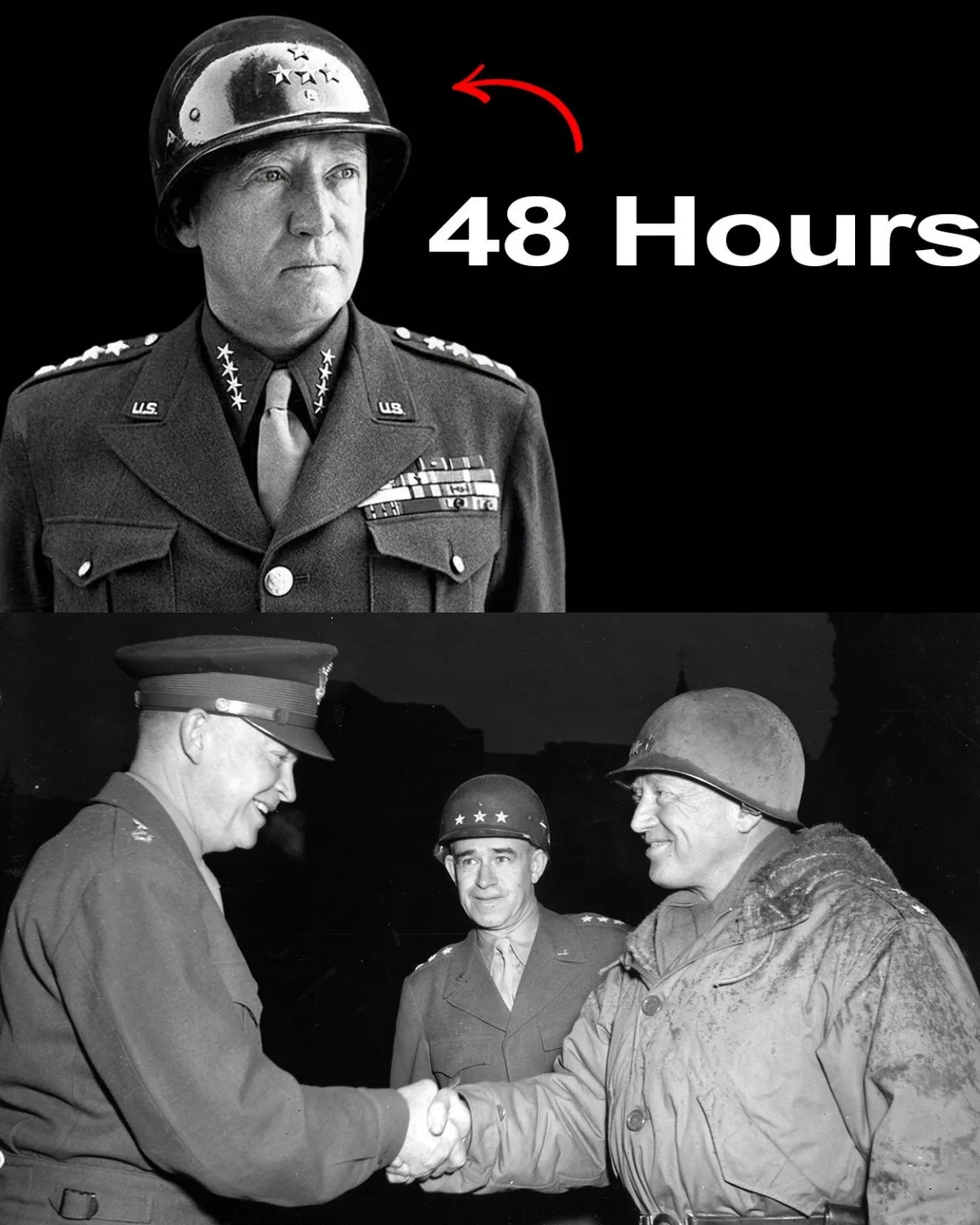

“They Laughed When He Said ‘48 Hours’: Why Patton Was the Only Man Ready When the Ardennes Exploded”

I. Verdun, December 19 — The Silence Before Judgment

The room was heavy with failure.

Inside a converted French barracks in Verdun, the most powerful Allied commanders in Europe sat around a table cluttered with maps that no longer made sense. Three days earlier, the German army—written off as exhausted, broken, finished—had erupted through the Ardennes Forest with more than 200,000 men.

Entire American units had vanished.

Roads were clogged with refugees, retreating troops, shattered equipment. Snow swallowed bodies faster than burial details could reach them. And now Dwight D. Eisenhower asked the question that decided everything:

“How soon can someone attack north to relieve Bastogne?”

No one answered.

Every general in that room understood the mathematics. To disengage forces already fighting, rotate an army ninety degrees, move men and machines through frozen roads, and attack a hardened enemy—it was operational fantasy.

Then George S. Patton spoke.

“I can attack with two divisions in 48 hours. Three in 72.”

The silence that followed was not awe.

It was disbelief.

They thought Patton was performing.

They were wrong.

II. The Difference Between Shock and Surprise

The Battle of the Bulge is remembered as a German surprise.

That is only half true.

It was a surprise to Allied headquarters—but not because the signs weren’t there. The signs were everywhere. They were simply inconvenient.

Fifteen German divisions had vanished from the front.

Not battalions.

Not regiments.

Divisions.

Including panzer units.

At Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, the explanation was soothing: reserves. Defensive posture. Nothing to worry about.

Only one intelligence officer disagreed.

His name was Oscar W. Koch.

And he worked for Patton.

III. The Intelligence Everyone Ignored

Koch was Third Army’s G-2—quiet, methodical, relentless. He tracked German radio traffic. Civilian reports. Prisoner interrogations. Rail movements.

What he saw didn’t fit the narrative.

The Germans weren’t conserving strength. They were concentrating it.

The Ardennes, thinly held by inexperienced American divisions, was not a defensive backwater. It was an invitation.

Everyone else remembered 1944.

Koch remembered 1940.

So did Patton.

The Ardennes had been “impassable” once before—right until German armor poured through it and broke France.

When Koch laid his maps on Patton’s desk, he didn’t hedge.

“General, I believe the Germans will attack here. Within two weeks.”

Patton didn’t argue.

He gave an order.

“Start planning.”

IV. Preparing for a War Nobody Believed Would Happen

From December 9 onward, Third Army did something no other Allied force did.

It prepared to fail forward.

Three full contingency plans were written—A, B, and C—each timed to the hour. Fuel dumps were quietly repositioned. Truck routes surveyed. Artillery assignments pre-calculated.

Patton never announced why.

He simply told his commanders to be ready to disengage on short notice.

They thought he was paranoid.

Patton thought they were complacent.

V. December 16 — When the World Caught Fire

At 5:30 a.m., the Ardennes erupted.

German artillery shattered the dawn. Infantry followed. Then armor. American divisions holding “quiet sectors” were crushed under four-to-one odds.

The 106th Infantry Division disintegrated. Two regiments surrendered—the largest American mass surrender of the European war.

At Allied headquarters, disbelief turned to panic.

At Third Army headquarters, Patton turned to Koch.

“You were right. What’s their objective?”

Koch answered without hesitation.

“Bastogne. Then Antwerp.”

Patton nodded.

“Execute the plans.”

VI. Why 48 Hours Wasn’t a Bluff

When Patton said “48 hours” at Verdun, he wasn’t predicting.

He was reporting.

Orders had already gone out. Units were already moving. Supply lines were already shifting.

While other generals were still deciding what had happened, Third Army was responding.

This was not genius.

It was preparation meeting reality.

VII. Turning an Army in Winter

What followed was one of the greatest logistical feats of the war.

Over 100,000 men.

More than 130,000 vehicles.

Tanks, artillery, fuel convoys, ambulances.

All pivoted north through snow and ice.

Engaged units disengaged under fire. Units fought one day in the Saar and another two days later outside Bastogne.

No pauses. No resets.

Just movement.

By December 21, lead elements of Third Army were in position.

By December 22, they attacked.

VIII. Bastogne: Held, Then Saved

Inside Bastogne, the 101st Airborne Division was surrounded.

Cold. Hungry. Low on ammunition.

When the Germans demanded surrender, Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe replied with one word:

“Nuts.”

They could say that because Patton was coming.

On December 26, tanks of the 4th Armored Division broke through.

The siege was over.

IX. The German Side of the Story

After the war, captured German commanders admitted something uncomfortable.

They expected a slow, confused Allied response.

They expected time.

They did not expect Patton.

General Hasso von Manteuffel later wrote:

“We knew Patton would react quickly.

We did not know he had prepared for our attack.”

That difference cost Germany the offensive.

X. Why Only One General Was Ready

Patton did not have better intelligence.

Others saw the same reports.

The difference was belief.

Most Allied commanders believed the war was almost over. Every piece of evidence was filtered through that assumption.

Patton believed the enemy still had teeth.

And he listened to the one man who proved it.

XI. The Aftertaste

The Battle of the Bulge is remembered for courage in foxholes and frozen forests.

But its outcome was decided earlier—in a quiet office, when a general chose to trust his intelligence officer instead of comforting assumptions.

Patton was not lucky.

He was ready.

And when war punishes complacency, readiness becomes destiny.