“They Mocked the Bookworm Pilot — Until His Calculated Trick Confused Six Enemy Fighters”

In the summer of 1943, over the steaming jungles of New Guinea, an American bomber crew prepared for the moment every airman feared.

Six enemy fighters were circling above them.

Their aircraft was damaged.

One engine smoked.

Fuel was tight.

Every rule in every flight manual said the same thing:

Run. Stay fast. Don’t slow down.

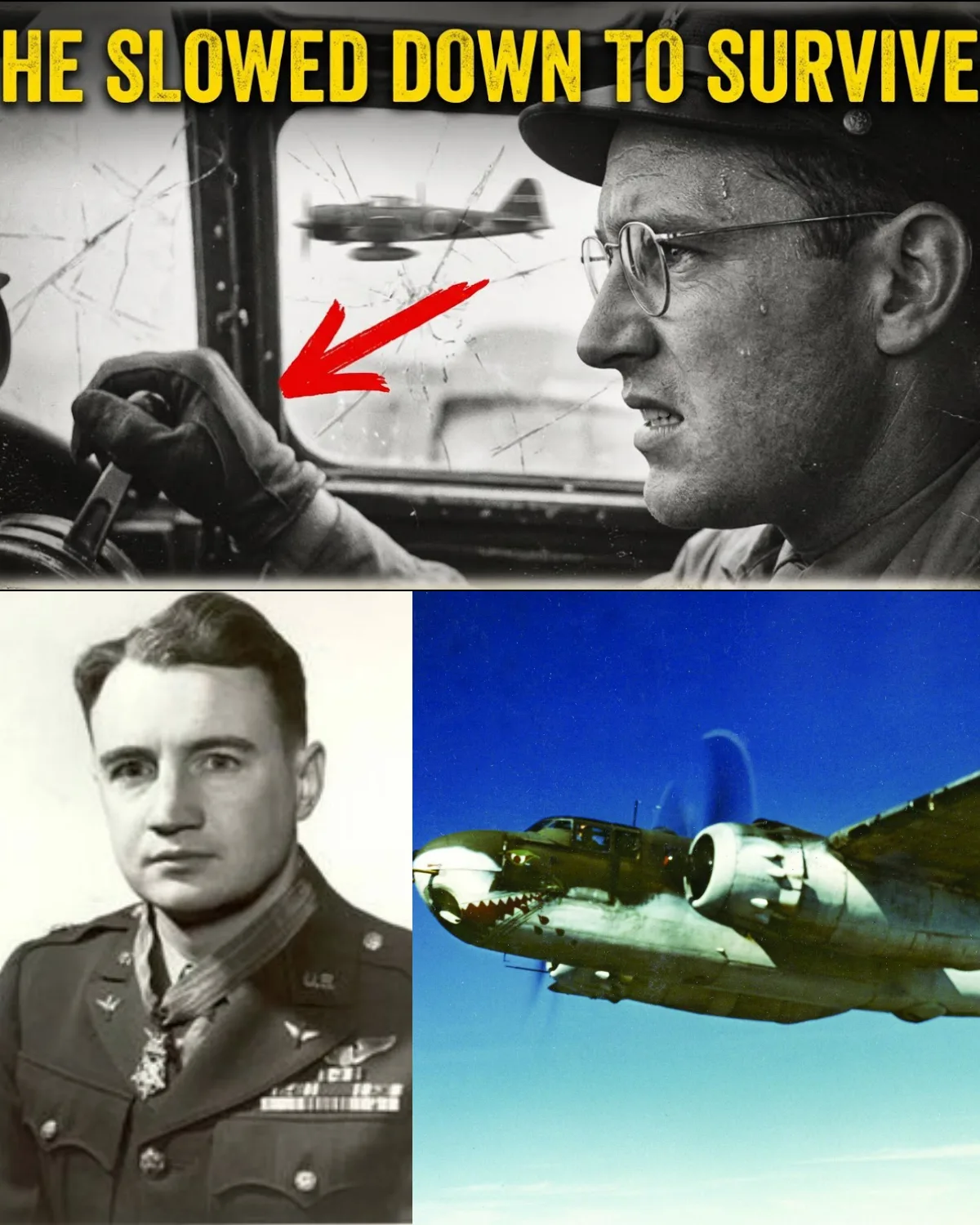

But their pilot—a quiet man with wire-rim glasses and an MIT education—did something no one expected.

He throttled back.

I. The Pilot No One Took Seriously

Captain Jay Zeamer Jr. did not look like a warrior.

Tall. Thin. Soft-spoken.

A civil engineering graduate from MIT.

A man more comfortable with equations than bravado.

Other pilots played cards and told stories.

Zeamer read technical manuals, enemy doctrine, and after-action reports.

Behind his back, they called him the bookworm.

Commanders saw him as hesitant.

Too analytical.

Not aggressive enough.

So he was shuffled between squadrons—useful, but never favored.

II. The Pacific Air War Problem

In 1943, the Fifth Air Force was bleeding aircraft.

Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters were lighter, more agile, and flown by veterans who had mastered close-range combat.

American bombers were big, fast in a straight line—and predictable.

Once Zeros caught them, escape was unlikely.

Doctrine offered only one answer:

Full throttle and pray.

Zeamer saw the flaw immediately.

If you can’t outrun them…

and you can’t out-turn them…

then speed isn’t the solution.

Timing is.

III. A Dangerous Idea

Zeamer began thinking in terms of energy.

A fighter attacking at high speed commits momentum.

It cannot instantly slow or adjust.

What if—at the exact moment of attack—the bomber slowed down?

Not randomly.

Not early.

Perfectly timed.

The fighter would overshoot.

For two or three seconds, the roles would reverse.

Two seconds, in air combat, is an eternity.

Everyone he told dismissed the idea as madness.

Slowing down meant death.

Or a stall.

Or both.

So Zeamer stopped talking about it.

And waited.

IV. The “Suicide” Mission

On June 16, 1943, Zeamer volunteered for a mission no one wanted.

Fly a battered B-25 Mitchell deep into Japanese-held territory near Bougainville.

No fighter escort.

Heavy enemy presence.

Low survival odds.

The mission was officially labeled voluntary.

His crew—misfits, overlooked men, veterans with scars—agreed to go.

Not because they were fearless.

Because they trusted Zeamer.

V. Six Fighters in the Sky

After completing the photo run, they turned for home.

That’s when the fighters appeared.

One Zero.

Then another.

Then four more.

Six in total.

Textbook formation.

Textbook patience.

They waited for the bomber to panic.

They waited for it to run.

The first attack tore into the tail.

Alarms screamed.

Hydraulics failed.

Zeamer watched carefully.

Counted spacing.

Measured angles.

Waited.

VI. The Moment Everything Changed

As a Zero committed to a stern attack and closed to lethal range—

Zeamer pulled the throttle back.

The bomber lurched.

The Zero screamed past, overshooting the target.

For the first time, the fighter was exposed.

The top gunner fired.

The Zero erupted in smoke and flame, spiraling down.

The others hesitated.

Bombers weren’t supposed to do that.

VII. Controlled Chaos

Zeamer repeated the maneuver.

Sometimes slowing.

Sometimes dropping flaps.

Sometimes changing altitude at the last instant.

Each attack run was disrupted.

Enemy timing shattered.

Zeros overshot.

Burned fuel.

Broke formation.

Some disengaged damaged.

Others fled outright.

The bomber limped home riddled with over 500 bullet holes.

But every man lived.

VIII. The Aftermath

Intelligence officers focused on the photographs—priceless reconnaissance.

But pilots focused on something else.

A bomber that survived six fighters by slowing down.

Zeamer explained it calmly during debrief:

Energy states.

Momentum.

Timing.

He wasn’t improvising.

He was executing math.

Three days later, Zeamer and his crew received the Medal of Honor and distinguished service awards.

Official citations spoke of courage.

They did not mention the throttle trick.

Unofficially, the idea spread like wildfire.

IX. A Quiet Revolution

Flight instructors didn’t write it into doctrine.

But they talked about it.

Advanced crews experimented.

Not recklessly.

Not always successfully.

But often enough.

Bomber survival rates in the Pacific rose measurably.

Just a few percentage points.

That meant hundreds of lives.

Zeamer never flew combat again due to his wounds.

He spent the rest of the war training pilots to think—not just react.

X. Legacy of a Bookworm

After the war, Jay Zeamer Jr. returned to civilian life.

He became an engineer.

Built bridges.

Raised a family.

He never boasted.

Never chased fame.

He died in 2007, quietly.

But his idea lived on.

In flight schools.

In combat doctrine.

In the understanding that:

Survival isn’t always about speed.

Sometimes it’s about being unpredictable.

Sometimes the smartest move is the one that feels wrong.

They mocked the bookworm pilot.

Until six enemy fighters learned—too late—that physics doesn’t care about bravado.