They Said He Gambled the Rhine on Speed — Until Black Gunners Held the Sky for 28 Minutes and Forced Patton to Put His Faith in Writing

In March 1945, the war was already lost for Germany.

Everyone knew it.

But wars are not ended by knowledge. They are ended by crossings.

The Rhine was not just a river. It was a psychological wall. For five years, it had marked the boundary between Germany at war and Germany under invasion. Every doctrine said you crossed it slowly, deliberately, under massive artillery cover. You crushed the banks. You blinded the enemy. You erased resistance before your first soldier touched the water.

That was how Field Marshal Montgomery planned to do it.

But George S. Patton despised symmetry and hated waiting.

While Montgomery stockpiled shells and wrote orders, Patton chose speed. Silence. Surprise. And a town few Germans believed anyone would dare to use.

Oppenheim.

Patton would cross the Rhine there without an artillery barrage. No smoke screens. No warning thunder. Just infantry rowing in the dark, engineers throwing bridges across open water, and a prayer that the Luftwaffe wouldn’t arrive in time.

What made that gamble survivable was not Patton’s confidence.

It was the men he trusted to hold the sky.

I. The Crossing That Should Have Failed

The night of March 22nd, 1945, was quiet in the way that only precedes catastrophe.

The Fifth Infantry Division slipped onto the river in assault boats, paddles muffled, breath held. German sentries were caught off balance. By midnight, American troops were already on the east bank. Engineers followed, hands numb, racing to assemble pontoon bridges before daylight betrayed everything.

Patton knew the math.

No artillery preparation meant German airfields were intact. The moment the sun came up and revealed floating bridges packed with men and vehicles, the Luftwaffe would come.

If the bridges went down, the infantry on the far bank would be isolated and destroyed.

There would be no retreat.

Between that fate and success stood one thin shield: anti-aircraft fire.

And the unit tasked with creating it was the 452nd Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion—a Black unit in a segregated army that still doubted whether Black soldiers belonged in combat roles at all.

Patton did not care about that debate.

He cared about results.

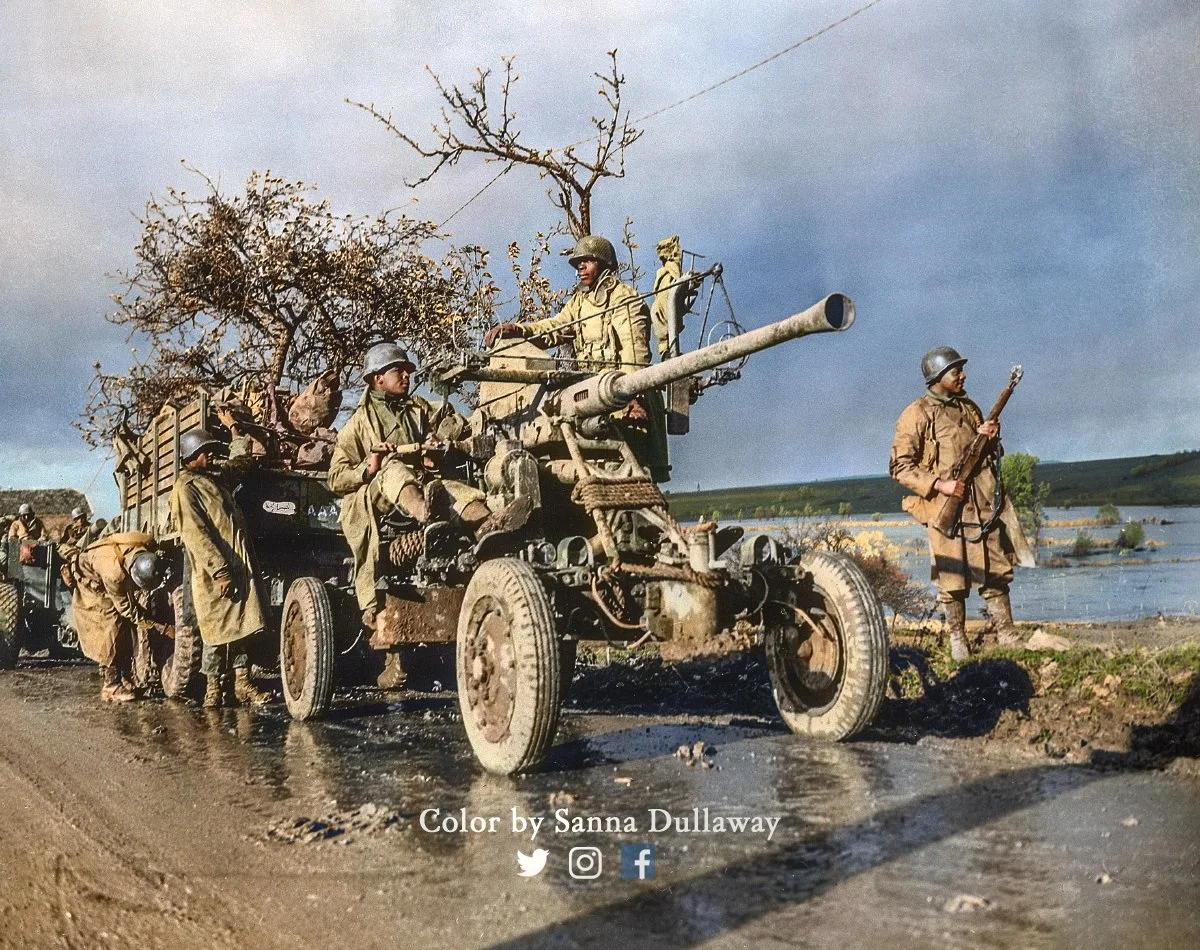

II. The Men at the Guns

The 452nd was an automatic weapons battalion. That meant mobility, speed, and brutal efficiency.

They brought two tools to the Rhine:

The Bofors 40mm cannon—high-explosive shells capable of ripping aircraft apart with a single hit.

And the M45 Quad .50 caliber mount—four machine guns firing together so violently it earned the nickname the meat chopper.

These were not symbolic assignments. They were precision instruments, placed exactly where failure would be unforgivable.

The gunners dug in along both banks of the river, some crossing before dawn to establish fire positions on German soil. They worked in darkness, leveling guns without lights, assigning sectors of fire by memory and whispered orders.

They knew what was coming.

And they knew that if they flinched, thousands of men would pay for it.

III. Dawn and the Swarm

March 23rd, 1945.

Dawn lifted like a curtain.

From German observation posts and reconnaissance aircraft, the scene was unmistakable: American bridges spanned the Rhine. Trucks rolled. Tanks waited their turn. The invasion of Germany had begun.

The Luftwaffe reacted with desperation.

Radar screens filled. Reports later estimated nearly 150 sorties aimed at the Rhine crossings that day. Messerschmitt Bf 109s and Focke-Wulf 190s came in low, hugging the river valley, diving hard to drop bombs and rake the bridges with cannon fire.

At Oppenheim, the first engines were heard before they were seen.

Then the sky screamed.

IV. Twenty-Eight Minutes

The 452nd opened fire.

Quad .50s poured red tracer fire upward in continuous streams. Bofors guns thumped methodically, explosive shells bursting in disciplined patterns, not sprayed wildly but walked into the paths of diving aircraft.

The Luftwaffe tried to overwhelm them.

Attacks came from multiple angles. High-speed dives. Strafing runs timed to catch gunners reloading. Planes so low that pilots could see faces behind gun shields.

For a period remembered in unit histories as roughly 28 minutes, the attack was continuous.

The gunners did not break.

Barrels overheated. Loaders burned their hands swapping ammunition cans. Orders were shouted over the roar. Targets were prioritized—bombers lining up on the bridges first, fighters second.

Planes began to fall.

Witnesses on both banks saw wings shear off, fuselages tumble into the river, burning wreckage slam into fields. Smoke rose. The sky filled with flak bursts and spiraling debris.

When the guns finally paused, the bridges were still floating.

Traffic resumed.

The river crossing lived.

V. What Everyone Saw

The results were undeniable.

Official records credited the Oppenheim sector with dozens of destroyed or damaged aircraft that day. A significant share belonged to the men of the 452nd.

But numbers were not what mattered most.

What mattered was who saw it.

White infantrymen waiting their turn to cross had watched German planes dive—and watched Black gunners stand their ground and annihilate them. Cheers went up along the riverbanks, spontaneous and unforced.

In that moment, race dissolved under necessity.

All that mattered was that the bombs missed.

VI. Patton Notices

Patton was not sentimental.

He was demanding, harsh, and shaped by a segregated system he rarely questioned. But he measured men by effect, not theory.

When he arrived to inspect the expanding bridgehead, he saw intact crossings pumping the Third Army into Germany. He saw wrecked German aircraft scattered around Oppenheim. He understood exactly how close his gamble had come to disaster.

And he understood who had prevented it.

Patton did something that surprised his own staff.

He wrote.

He issued a formal commendation praising the anti-aircraft units defending the crossing, citing their accuracy, fire discipline, and decisive role in defeating the Luftwaffe attack.

For the men of the 452nd, that paper mattered more than a medal.

It was proof—signed by the most aggressive general in the Allied armies—that competence, under fire, could not be denied.

VII. The Quiet Revolution

In military terms, commendations are routine.

In 1945, for a Black unit, they were not.

The irony was impossible to ignore. These men were fighting a Nazi regime obsessed with racial hierarchy while serving in an American army still segregated by law. They could be trusted with the most advanced weapons on the battlefield—but not with equal treatment off it.

Yet on the Rhine, reality forced honesty.

Prejudice was a liability.

Competence was decisive.

The 452nd didn’t just meet expectations. They exceeded them when failure meant catastrophe.

VIII. After the Smoke Cleared

Because the bridges stood, the Third Army broke into Germany. The collapse accelerated. Less than two months later, the war in Europe was over.

The men of the 452nd went home quietly.

No parades. No headlines. Many returned to the same discrimination they had left behind.

But history does not always move at the speed of gratitude.

Units like the 452nd, the 761st Tank Battalion, and the Tuskegee Airmen created a record that could not be erased.

Three years later, in 1948, the U.S. military was officially desegregated.

That decision was not born only from politics.

It was forged in moments like Oppenheim—when men stood at their guns, under diving aircraft, and proved that excellence has no color.

IX. The Aftertaste

Maps show arrows crossing rivers.

History books summarize campaigns.

But wars turn on minutes.

On March 23rd, 1945, for 28 minutes over the Rhine, the future of an army depended on men who had every reason to doubt whether that army truly believed in them.

They held anyway.

And Patton, for once, did not speak loudly.

He put it in writing.