“They Said the Survivors Would Die Anyway—Then a ‘Crazy’ Canadian Officer Moved an Entire Camp and Shattered Medical Orthodoxy, Turning Certain Death Into 34,000 Lives Saved”

1. Liberation That Smelled Like Death

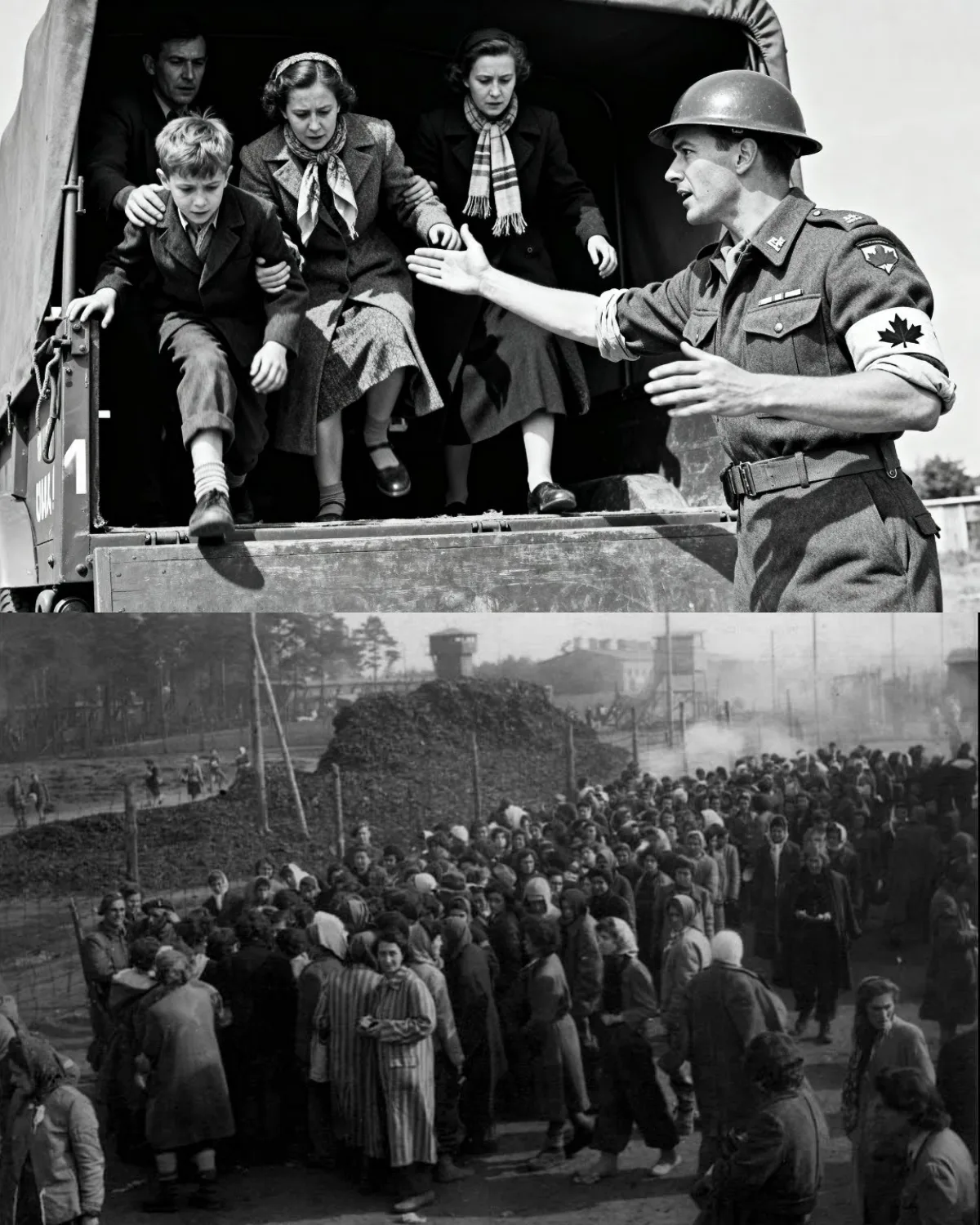

April 1945. When British and Canadian armored units smashed through the gates of Bergen-Belsen, they expected victory.

What they found instead was annihilation still in progress.

The smell hit first—a physical wall of rot and disease so thick that hardened soldiers vomited where they stood. Then the bodies. Stacked like lumber between barracks. Tens of thousands of prisoners, reduced to bone and skin, drifting through mud mixed with human waste.

This was liberation.

And it was killing people faster than the Nazis had in their final weeks.

In the first days after Allied forces arrived, 400 prisoners died every single day. Not from bullets. Not from gas chambers. They died after being saved.

Medical teams followed every rule they had ever been taught. Clean water. Controlled feeding. Careful treatment. Isolation where possible. It was textbook medicine.

And it was failing catastrophically.

2. When Doing Everything Right Still Kills People

Doctors watched survivors die hours after their first real meals. Their bodies could not process food. Others drank water too fast—hearts stopped. Typhus spread faster than it could be isolated.

Meetings were held. Charts were reviewed. More doctors arrived. More supplies followed.

Nothing changed.

A senior British medical officer finally said what no one wanted to admit:

“Given their condition, we should consider ourselves fortunate if half survive.”

The math was brutal. At this rate, 30,000 more people would die within two months—after liberation.

The experts accepted it as unavoidable.

One man did not.

3. The Officer Who Didn’t Belong in the Room

Lieutenant Colonel Ben Dunkelman was 28 years old.

He was not a doctor. He had no medical credentials. He was a frontline combat officer who had fought from Normandy across Europe. And he was Jewish.

The people dying in Bergen-Belsen looked like his family. His grandparents. His cousins. People who could have lived on his street in Toronto.

He walked the camp for hours, forcing himself to see everything. Not individual patients—but the system.

Fifty people crammed into spaces meant for ten. One water pump for thousands. Doctors treating one patient carefully while hundreds waited outside.

That night, Dunkelman wrote by lamplight.

The problem wasn’t medicine.

The problem was scale.

4. The Idea That Sounded Like Madness

Doctors were trying to save individuals.

What needed saving was a population.

Dunkelman’s idea was simple—and professionally insane:

Move them. All of them.

Get survivors out of the infected death trap. Spread them across multiple locations. Use empty German barracks, schools, factories—anywhere with space and air.

Move the sickest first.

Move them fast.

Yes, transport was dangerous. Patients could die en route. Medical textbooks said so.

Dunkelman did the math anyway.

If 400 died daily by staying, even a 3% transport death rate would save thousands.

Following the rules was killing people.

Breaking them might not.

5. “Sit Down, Lieutenant Colonel”

When Dunkelman presented his plan, laughter broke out.

A British medical colonel stood up, furious:

“You want to move dying patients? You will kill them faster than typhus. Sit down.”

Dunkelman stayed standing.

“Right now,” he said, “we’re losing 12% a day. If transport kills 3%, we still save 9%. That’s 360 lives per day.”

Silence.

Finally, Brigadier Glenn Hughes intervened.

“You get 500 patients,” he said. “One test. If you’re wrong, this ends.”

6. The First Convoy

At dawn, Dunkelman commandeered everything that could move.

German army trucks. Abandoned ambulances. Civilian buses. Volunteers. Nurses. Orderlies willing to try the impossible.

Patients were fed precisely—small meals, controlled water. Blankets packed tight. Nurses rode in every vehicle.

The convoy moved at walking speed over cratered roads.

Three hours later, they reached intact buildings outside the camp.

Space.

That was the miracle.

7. Numbers That Changed Everything

After 24 hours:

15 of the 500 moved patients had died → 3%

60 of the 500 left behind had died → 12%

The idea worked.

Better than anyone imagined.

Brigadier Hughes reviewed the data twice.

Then he authorized the full evacuation.

8. Eight Days That Saved 34,000 Lives

What followed was logistical insanity.

34,000 people

12 locations

187 vehicles

2,000 German POWs pressed into labor

400 medical personnel

8 days

Trucks became moving hospitals. Care continued en route. Food schedules were enforced. Disease spread slowed. Air returned to lungs that had forgotten what breathing felt like.

Deaths dropped from 400–500 per day to 50–80.

An 85% reduction.

The camp of death became a network of survival.

9. The Court-Martial That Never Came

Three days in, Dunkelman was summoned.

Senior officers accused him of reckless endangerment, misuse of enemy resources, insubordination.

By regulation, they were right.

Then Brigadier Hughes read the numbers.

Projected deaths: 30,000

Actual deaths so far: under 2,000

The room went quiet.

No charges were filed.

No medals were given.

10. Erased From the Record, Embedded in History

Official reports praised “improved medical coordination.”

Dunkelman’s name appeared nowhere.

But the military remembered the lesson.

By 1950, NATO adopted mass casualty evacuation doctrine based on Bergen-Belsen. Korea used it. Vietnam perfected it. Modern medevac was born.

Move first. Treat continuously. Spread people out. Save populations, not just patients.

A Canadian officer with no medical training rewrote combat medicine.

11. Why This Story Matters

Dunkelman was not smarter than doctors.

He was not braver than soldiers.

He was simply willing to be wrong when being right meant death.

Sometimes rules save lives.

Sometimes they kill them.

At Bergen-Belsen, sanity looked like madness—and madness saved 34,000 futures.

That is not a miracle.

That is courage with math.