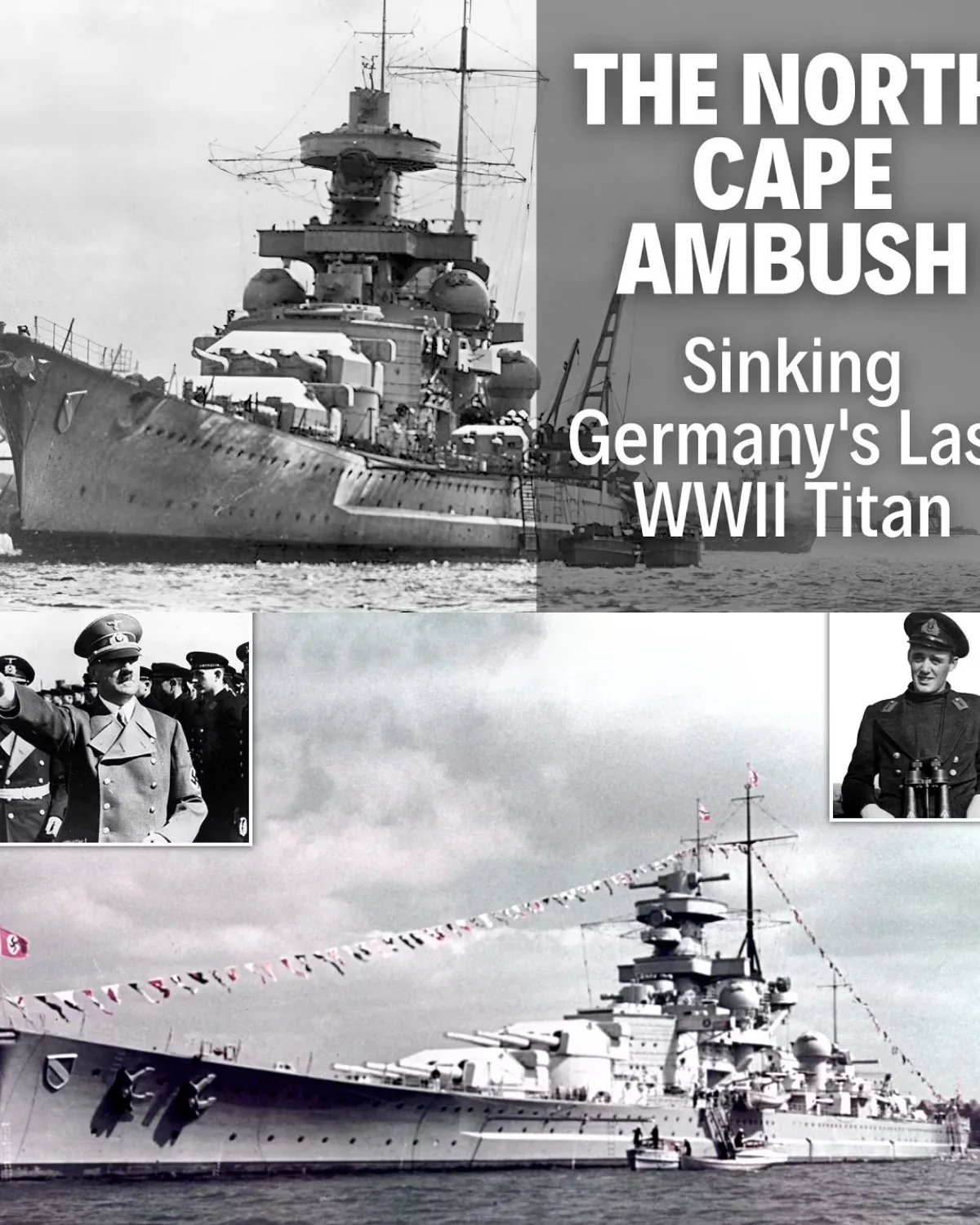

They Thought Speed Was Enough

How the Royal Navy Hunted Germany’s Fastest Warship in the Arctic Dark

The Arctic Ocean, December 1943

The sea was black—thick, oily, and indifferent.

In the Arctic winter, darkness was not the absence of light but a presence of its own. For weeks at a time, the sun never rose. The horizon dissolved. Depth perception vanished. Men learned to navigate by instruments alone, trusting needles, dials, and the cold glow of radar screens more than their own eyes.

It was into this void that Germany sent one of its last great surface warships.

She was fast. She was feared. And her crew believed speed would save them.

They were wrong.

The Convoys That Could Not Fail

By late 1943, the war on the Eastern Front consumed nearly everything Nazi Germany could produce. Eighty percent of its army was locked in a grinding, annihilating struggle against the Soviet Union. What kept the Red Army alive—its tanks, aircraft, trucks, fuel, food—came from the west.

Across the Arctic.

From Iceland and Scotland to the frozen ports of northern Russia ran a thin, brutal lifeline. The Arctic convoys were among the most dangerous operations of the war. Ships iced over so heavily they threatened to capsize. Sailors froze to death at their stations. A man in the water survived minutes—if that.

But the cold was not the greatest danger.

The true threat lay in the Norwegian fjords.

Germany’s Fleet in Being

Hitler understood something fundamental about naval warfare: a ship did not have to sail to be dangerous. The mere existence of a powerful enemy warship forced the Royal Navy to divert enormous resources to counter it.

This was the doctrine of the “fleet in being.”

Germany’s surface fleet rarely left port by 1943, but when it did, it sent shockwaves through Allied command. A single sortie could force Britain to deploy battleships, cruisers, and destroyers—assets desperately needed elsewhere.

The most feared of these ships was not the massive battleship lurking deeper in Norway.

It was her faster sister.

The Fast Raider

She had been designed for a specific purpose: strike commerce and escape.

Unlike traditional battleships built to slug it out line-of-battle style, this ship sacrificed armor and gun caliber for speed and range. She could maintain over 30 knots in heavy seas—fast enough to outrun most opponents.

Her guns were smaller, but accurate. Her crew was highly trained. Her reputation was already legend.

She had embarrassed the Royal Navy before—most famously during a daylight dash through the English Channel that should never have succeeded.

To German sailors, she was proof that engineering and daring could overcome numerical superiority.

To British admirals, she was unfinished business.

A Mission Born of Desperation

By December 1943, Germany’s surface fleet was living on borrowed time. Hitler despised it. After earlier setbacks, he had openly considered scrapping the remaining capital ships entirely.

Only fierce arguments from naval leadership kept them afloat.

This mission—an attack on Arctic convoy JW-55B—was more than tactical. It was existential. Success would justify the surface fleet’s survival. Failure would confirm its irrelevance.

The order came on Christmas Day.

In heavy snow and worsening seas, the ship slipped from her fjord with five destroyers and vanished into the polar night.

Unknown to her crew, the hunt had already begun.

The British Were Waiting

At Royal Navy headquarters, the sortie triggered no panic.

It triggered a plan.

The British commander was a meticulous gunnery specialist who believed the future of naval combat no longer belonged to optics and intuition. It belonged to information.

And he had it.

Intercepted German signals—decoded through Ultra intelligence—had revealed everything: sailing time, intended route, mission objective. The German ship was moving along a path already mapped in red grease pencil.

The British response was calm, deliberate, and lethal.

Two forces moved to intercept.

The Trap

The first force consisted of cruisers—lighter, faster, and vastly outgunned. Their task was not to win. It was to find, harass, and herd.

They would act as bait.

The second force was the executioner.

At its center steamed a modern battleship equipped with something no German commander fully understood: radar-directed gunnery refined through relentless Arctic training.

British crews had practiced firing blind—no stars, no silhouettes, no horizon. Just electronic echoes and disciplined calculation.

This battle would not be fought by men squinting through optics.

It would be fought by machines.

First Contact: A Battle Without Sight

On the morning of December 26th, the first contact came—not visually, but electronically.

A blip appeared on a cruiser’s radar screen.

Large. Metallic. Moving fast.

The German ship had been found.

Moments later, star shells burst overhead, turning the darkness into a harsh, frozen stage. For the first time that day, the German crew saw their enemy—and realized they had been surprised.

They returned fire immediately.

But in driving snow and near-total darkness, their optical rangefinding was nearly useless.

British shells—guided by radar—were not.

Within minutes, a cruiser’s shell struck the German ship’s forward radar equipment.

The damage seemed minor.

It was not.

In one moment, the fastest warship in the Kriegsmarine went blind.

Blind Speed Is Not Enough

The German commander did what doctrine and instinct demanded.

He turned away.

Relying on speed, he broke contact and disappeared into the storm. For a brief moment, it seemed the escape had worked.

The British cruisers did not pursue aggressively.

They didn’t need to.

They followed electronically.

The German ship, believing herself free, made a fatal decision—turning back to circle toward the convoy, unaware that she was steering directly into the second force.

Into the executioner.

The Battleship Appears

Late that afternoon, as darkness thickened into absolute night, the radar operator aboard the British battleship called out the contact.

A large echo. Closing.

The range collapsed steadily.

The British commander waited.

He let the distance shrink until his guns would strike with maximum force. This was not haste. It was calculation.

At just under twelve thousand yards, the order was given.

Fire.

When Technology Decides Fate

The German crew saw shell splashes before they ever saw muzzle flashes.

Massive armor-piercing rounds—each weighing nearly a ton—slammed into the ship with devastating precision. Radar-directed fire meant the British guns corrected instantly, walking shells across decks, turrets, and superstructure.

The German ship fired back blindly, aiming at flashes and guesses.

It was no longer a duel.

It was an execution.

Shell after shell tore into machinery spaces, started uncontrollable fires, severed communications, and killed power. The speed that had once been her salvation vanished as boilers failed and steam lines ruptured.

When her speed dropped below ten knots, the end was inevitable.

The Final Act

Destroyers raced in through exploding spray and tracer fire.

At close range, they launched torpedoes—carefully aimed to finish what artillery had begun. Some took hits in return. Men died. Ships burned.

But the German ship could not fight physics.

Multiple torpedoes tore open her hull. Flooding spread uncontrollably. The deck listed.

The commander sent a final signal.

“We shall fight to the last shell.”

Minutes later, the ship rolled, capsized, and disappeared beneath the Arctic sea.

Of nearly two thousand men aboard, only a few dozen survived long enough to be pulled from the freezing water.

Aftermath in the Darkness

Rescue efforts were brief and agonizing.

The threat of submarines forced the British to withdraw. Staying meant risking the entire fleet—and the convoys still at sea.

It was a cold calculation. War often is.

The Arctic swallowed the rest.

What Was Really Destroyed

The sinking did more than remove a ship.

It ended an era.

No German surface warship would ever again seriously threaten Allied convoys. The surviving capital ships became political symbols—trapped in fjords, waiting for bombs.

The fleet in being ceased to exist.

From that night forward, naval warfare belonged to information, coordination, and electronic eyes—not speed alone.

The Lesson Written in Ice

German sailors believed they could outrun anything.

They believed darkness was protection.

They believed speed was invincibility.

The Royal Navy proved otherwise.

In the Arctic night, the fastest ship afloat was hunted, blinded, and destroyed—not by chance, not by courage alone, but by preparation, intelligence, and technology applied without hesitation.

The sea closed over her without ceremony.

And the convoys kept sailing.