They Tried to Expel the “Reject” Eight Times — Until He Stood Between 700 Germans and the Collapse of the Front

The U.S. Army had already decided what Jake McNiece was.

Unmanageable.

Violent.

Undisciplined.

On paper, he was a mistake that refused to go away.

Eight disciplinary actions.

Multiple assaults.

Repeated insubordination.

Any other soldier would have been court-martialed and erased from the rolls.

But history has a way of keeping the wrong people alive for the moments that matter most.

And on one burned-out hill in Normandy, in June 1944, when surrender made perfect sense, the Army’s worst disciplinary case became the immovable object that stopped a German force twenty times larger.

I. The Man the Army Couldn’t Control

Jake McNiece grew up in Oklahoma during the Great Depression, one of ten children raised on whatever the land would give them. Hunger wasn’t theoretical to him. Neither was violence. Life taught him early that rules mattered only if they worked.

By nineteen, he was a firefighter.

Running into burning buildings while others ran out.

When Pearl Harbor happened, he didn’t wait for a draft notice. He volunteered—specifically for the airborne.

Not for glory.

Not for patriotism.

But because paratroopers went behind enemy lines with explosives.

And Jake liked explosives.

II. Discipline vs. Reality

From the first week at Fort Benning, Jake clashed with the Army’s idea of discipline.

When a staff sergeant stole his butter ration and laughed about it, Jake broke his nose. That should have ended his career.

Instead, Jake set a demolition-course record the same day.

That pattern followed him everywhere.

He ignored salutes.

Refused to polish boots.

Called officers “sir” only if he believed they’d earned it.

“I’m here to kill Nazis,” he told one lieutenant, “not polish leather.”

The officers hated him.

But they couldn’t replace him.

III. The Army’s Accidental Experiment

Instead of expelling Jake, the Army tried containment.

They gave him his own platoon inside the 101st Airborne Division, hoping to isolate the damage.

Then something strange happened.

Every soldier who didn’t fit—fighters, brawlers, rule-breakers, men too dangerous for regular units—got sent to Jake.

A coal miner who broke three MPs’ noses.

A multilingual black-market operator who could interrogate Germans better than officers.

A demolition expert who blew up a latrine just to see the blast pattern.

A Chicago boxer who won fourteen fights in basic training.

They became known as the Filthy Thirteen.

Dirty.

Disobedient.

Terrifyingly effective.

IV. Wolves, Not Soldiers

Jake didn’t train them like soldiers.

He trained them like hunters.

No parade drills.

No inspections.

No ceremony.

Only endurance, marksmanship, demolitions, and violence under pressure.

They ran farther.

Carried more.

Shot better.

And every official evaluation told the same uncomfortable truth:

They were the best-performing platoon in the division.

The Army despised everything they represented—and quietly depended on them.

V. War Paint and the Night of Fire

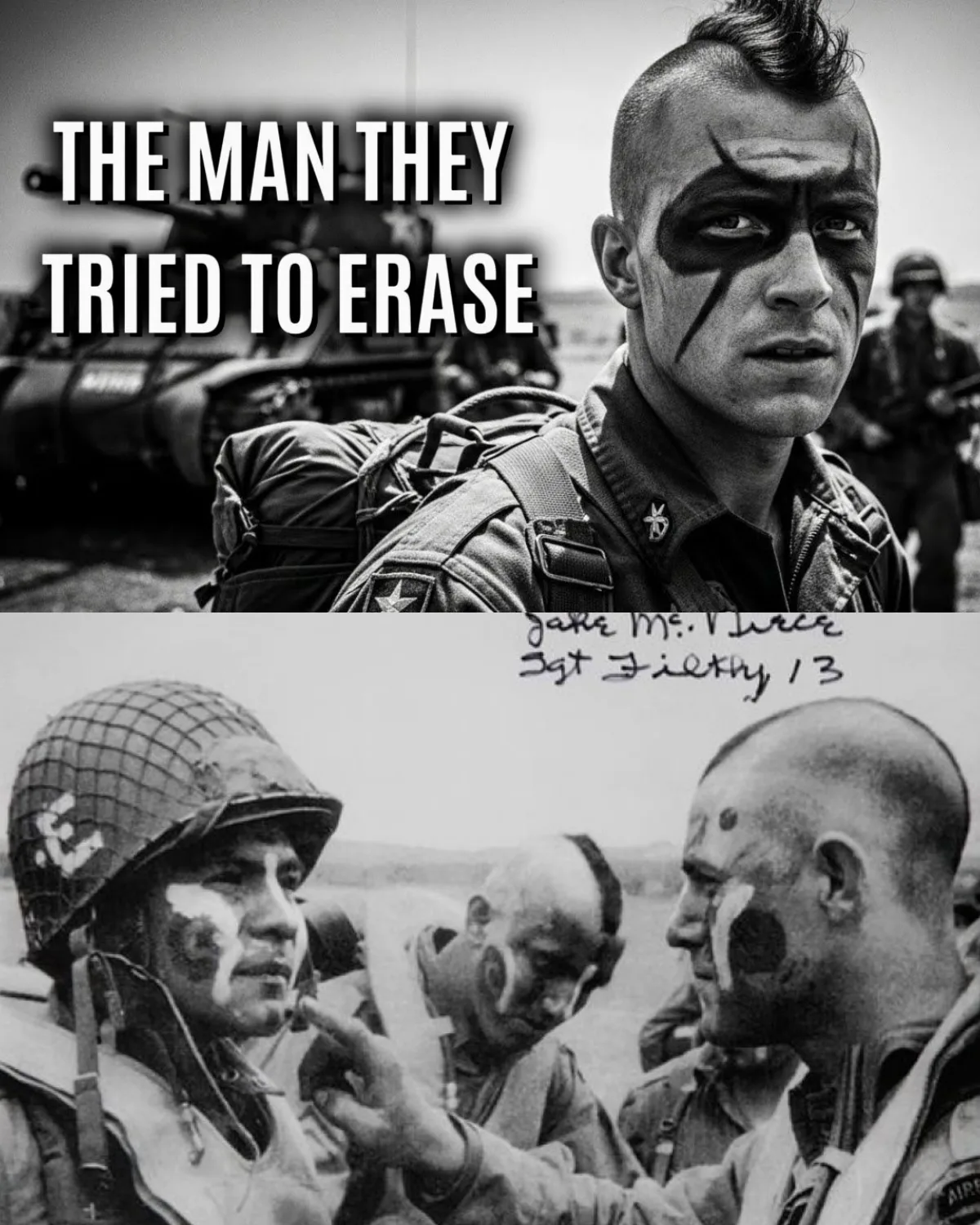

Days before D-Day, Jake shaved his head into a mohawk and painted white war stripes across his face. His men followed.

Not for publicity.

For transformation.

A Stars and Stripes photographer captured the image. It became iconic.

Within 48 hours, their plane was hit by German flak over Normandy.

The aircraft exploded.

Men were thrown into the night sky.

Jake fell into a flooded marsh with a burning parachute, cut himself free, and survived when most would have drowned.

He didn’t rest.

He hunted for survivors.

VI. Nine Men, Then Thirty-Five

By dawn, Jake had gathered nine paratroopers.

Their mission: seize and hold a bridge near Chef-du-Pont.

They attacked anyway.

Ambushes.

Disappearing acts.

Chaos.

Scattered airborne troops linked up with them. Nine became thirty-five.

By midday, they held the bridge.

Then American P-47 Thunderbolt pilots, acting on outdated orders, destroyed it.

Jake laughed.

Not because it was funny—but because it was predictable.

Now they were cut off.

No bridge.

No reinforcements.

No escape.

And German forces were regrouping.

VII. The Hill That Could Not Be Taken

Jake chose high ground overlooking three narrow approaches.

He didn’t need maps.

He saw geometry.

Funnels.

Choke points.

Angles of death.

He positioned machine guns with overlapping fire. Riflemen targeted officers first. Mortars were neutralized by terrain alone.

When a German officer arrived under a white flag, he didn’t come to surrender.

He came to demand it.

Jake listened patiently.

Then said:

“If you want it, start climbing.”

VIII. Five Waves, Zero Casualties

The Germans attacked in waves.

Infantry.

Mortars.

Artillery.

Tanks.

Every time, Jake let them enter the funnel.

Every time, the hill erupted.

German soldiers died by the dozens. Others broke and fled.

The tanks couldn’t elevate their guns high enough. Mortars overshot the reverse slope.

Jake’s men were starving. Dehydrated. Exhausted.

But none were hit.

After three days, over 100 Germans were dead or wounded.

American casualties: zero.

When relief finally arrived, an officer asked Jake for his casualty report.

“Zero,” Jake said.

“But if you brought food, we’ll take it.”

IX. Bastogne and the Mission No One Wanted

Six months later, the Germans launched the Ardennes offensive.

Bastogne was surrounded.

No roads.

No supplies.

Freezing temperatures.

The only hope was airborne resupply—guided by Pathfinders.

A suicide mission.

Jake volunteered instantly.

He jumped blind into fog and artillery, assembled surviving Pathfinders, and established covert beacons under fire.

For two days, under constant shelling, he guided 247 successful supply drops.

Food.

Ammunition.

Medicine.

Bastogne held.

Thousands lived.

Jake received no medal.

The operation was classified.

X. After the War, Silence

Jake survived the war.

Then nearly died from alcohol.

He quit drinking overnight.

Married.

Worked at a post office.

Raised children who never knew what he’d done.

He didn’t want glory.

He wanted peace.

Jake McNiece died in 2013, aged 93.

The Army tried to kick him out eight times.

Every time they failed, history bent slightly toward survival.

Because sometimes the people who don’t fit the system are the ones who save it.