It lay wrapped in thinning tissue paper inside a cardboard box labeled Miscellaneous Personal Effects, 1918–1925, forgotten on a metal shelf in the basement archive of the Greenwood County Historical Society. Dust softened its edges. Time yellowed its mount. But the faces inside it—five figures frozen in March of 1920—remained clear, watchful, and unresolved.

No one knew they were waiting to be understood.

1. The Discovery

At 4:30 p.m., with the archive closing in thirty minutes, James Mitchell was already mentally packing up for the day. The thirty-eight-year-old genealogologist from Chicago had spent hours reviewing land deeds and probate records, the unglamorous backbone of historical research. Names, dates, signatures. Nothing unusual. Nothing alive.

Then he opened the last box.

Inside were photographs—curling, water-stained, brittle. He lifted them one by one, until his hand stopped.

This one was different.

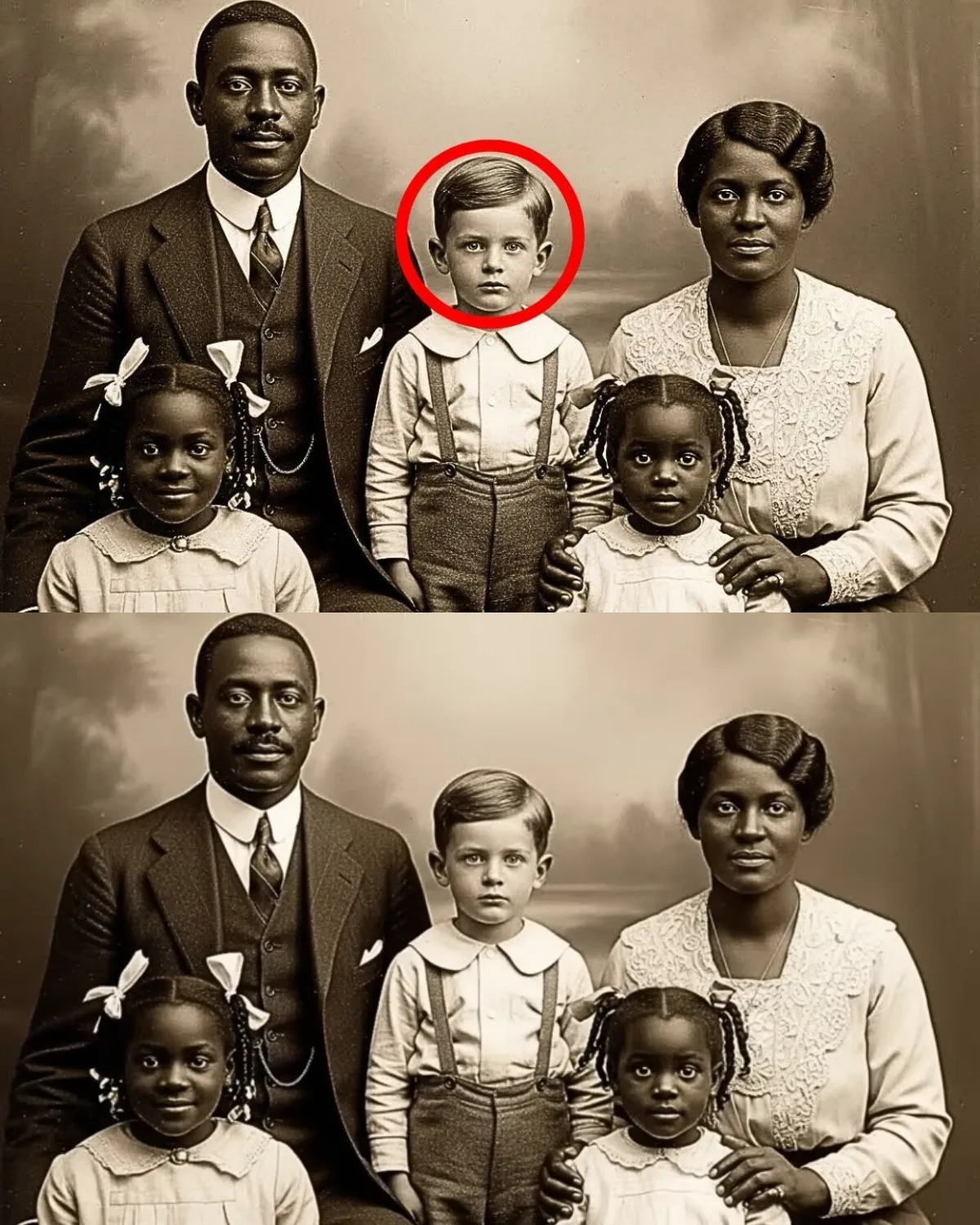

Mounted on thick cardboard, remarkably intact, the image carried a studio stamp at the bottom: Crawford Photography, Greenwood, Mississippi — March 1920. The composition was formal, deliberate. A black man and woman sat at the center, dignified, composed, wearing their best clothes. Three children stood behind them.

Two of the children made sense immediately: young black girls in white dresses, hair neatly braided, ribbons tied with care.

The third did not.

Between the girls stood a boy of about seven years old. His skin was pale. His hair light brown, almost golden in the sepia tones. His eyes—light, unmistakably so.

He was white.

James leaned closer, heart accelerating. The man’s hand rested naturally on the boy’s shoulder. Not stiff. Not cautious. Protective. Familiar. The boy did not look borrowed or posed. He belonged.

On the back, in faded pencil, five names were written in a steady hand:

Samuel. Clara. Ruth. Dorothy. Thomas.

March 14th, 1920.

James felt the weight of history settle heavily in his chest.

In Jim Crow Mississippi, a black family openly posing with a white child was not just unusual—it was dangerous. Potentially lethal. This photograph was not an accident. It was a declaration.

And someone, somewhere, had tried very hard to make sure it disappeared.

2. The First Questions

The archivist, Mrs. Patterson, recognized the photograph the moment she saw it. Her reaction was subtle but unmistakable—a tightening of the mouth, a pause too long.

“Samuel and Clara Johnson,” she said quietly. “Respected people.”

“And the boy?” James asked.

Mrs. Patterson hesitated. “There are stories,” she said. “Old ones. The kind folks didn’t write down.”

She glanced at the clock, then lowered her voice. “If you want to understand that picture, you should speak to Evelyn Price. She’s ninety-three. Her mother knew the Johnsons.”

Before James could ask more, Mrs. Patterson placed the photograph back into his hands.

“No one’s claimed it in seventy years,” she said. “Maybe it’s time.”

James left the building knowing he had crossed from research into revelation.

3. An Impossible Family

That night, James began with the census.

The 1920 records listed Samuel Johnson, thirty-two, carpenter. Clara Johnson, twenty-nine, seamstress. Two daughters: Ruth, ten, and Dorothy, eight.

No son.

No Thomas.

Birth records offered no clarity. No missing white child simply vanished into a black household. But newspaper archives did.

On February 3rd, 1920, a brief article appeared in the local paper:

Tragic Accident Claims Local Couple.

Robert Hayes, thirty-four, and his wife Margaret, twenty-nine, perished in a house fire on February 1st. They left behind one son, age six.

One son.

Six years old.

Six weeks later, a black family commissioned a formal portrait that included a white boy named Thomas.

James did not sleep that night.

4. The Witness

Magnolia Gardens nursing home smelled of disinfectant and old sunlight. Evelyn Price sat in a wheelchair by the window, thin hands folded neatly in her lap, eyes sharp behind wire-rim glasses.

She studied the photograph for a long time.

“Yes,” she said finally. “That’s them.”

Her memory unfolded slowly, carefully, like a long-guarded truth being set free.

The Hayes boy’s parents had died in the fire. He was alone. County officials planned to send him to the Greenwood County Children’s Home—an orphanage notorious for abuse, forced labor, and unexplained disappearances.

Samuel Johnson saw the boy sitting on the burned steps of his house.

“He went home and told Clara,” Evelyn said. “And Clara cried. But she said she couldn’t let a child go to that place. Not any child.”

They took him in during the night, before the county arrived.

Touching a white child in 1920 Mississippi could get a black man lynched. Housing one could get an entire family killed.

They did it anyway.

5. The Secret Network

The Johnsons told outsiders the boy was a visiting nephew. It was a fragile lie, but the black community protected it. Churches prayed in coded language. Neighbors watched. Silence became a shield.

And Samuel insisted on the photograph.

“He said if something happened,” Evelyn recalled, “there needed to be proof that child existed. Proof someone loved him.”

The photographer, Albert Crawford, was white. Samuel told him the truth.

Crawford took the picture anyway.

6. Proof in the Church Basement

Mount Zion Baptist Church held the missing half of the story.

In its basement archives, James found a ledger maintained by a meticulous pastor in the 1920s. There, in careful ink:

Samuel and Clara Johnson, daughters Ruth and Dorothy, and ward Thomas, age six.

Ward.

Not son. Not servant.

Family.

Pastoral notes revealed prayers for protection, collections taken to support the household, and private reflections that bordered on reverence.

“This is what Christianity truly means,” the pastor had written. “Love without safety.”

7. The Farewell

By 1922, the risk became unbearable.

The boy was growing. He could no longer pass unnoticed. The Ku Klux Klan was active again. Threats circulated.

Clara’s cousin in Chicago—a black woman married to a white union organizer—offered refuge.

They sent Thomas north.

Clara cried for weeks.

Letters arrived for years. Then they stopped.

The secret went dormant. The photograph vanished into a box.

8. The Lost Descendant

James followed the trail north.

Census records revealed a “nephew” named Thomas Hayes living quietly in Chicago. He became a carpenter. Married. Had children. Died in 1987, never speaking of Greenwood.

His grandson, Thomas Hayes Jr., taught high school history.

James reached out.

Two days later, they met.

When Thomas Jr. saw the photograph, he cried.

“They saved my grandfather,” he said. “Which means they saved all of us.”

9. The Reunion

The Johnson descendants were still there, too.

Some had guarded fragments of the story. Others carried only a sense of inherited gravity, a knowledge that their ancestors had done something dangerous and right.

Three months later, the families reunited at Mount Zion Baptist Church.

No cameras at first. No speeches. Just people standing in front of a photograph that had finally finished its work.

“This picture was taken as proof,” the pastor said. “And it worked.”

10. Legacy

The photograph now hangs in a national museum, its mystery replaced with meaning.

But its real legacy lives elsewhere.

In scholarships for foster children.

In restored headstones.

In names passed down deliberately.

In families joined not by blood, but by courage.

Samuel and Clara Johnson never sought recognition. They acted because a child needed saving.

A century later, the world finally noticed.

And the photograph—once hidden, once dangerous—no longer needs to whisper.

It tells the truth out loud.