Three Hours Alone at Guadalcanal: How One Marine Held the Line and Left 200 Enemy Dead

The Ridge That Could Not Fall

At 3:18 a.m. on October 26, 1942, a single American Marine stood behind a glowing, overheated machine gun on a jungle ridge south of Henderson Field. Around him lay the dead and wounded bodies of his fellow Marines. In front of him, barely visible in the darkness, hundreds of Japanese soldiers were forming up for another charge.

His name was Mitchell Paige.

If this ridge fell, Henderson Field would fall. If Henderson Field fell, Guadalcanal would fall. And if Guadalcanal fell, the momentum of the Pacific War might swing back to Japan.

Paige did not retreat. He did not surrender. He did not stop firing.

For three hours—much of it alone—he held the line.

A Working-Class Marine

Mitchell Paige was born in 1918 in a Pennsylvania coal town. He was not wealthy, not famous, not groomed for heroism. Like many young men during the Great Depression, he joined the Marines in search of steady pay and purpose.

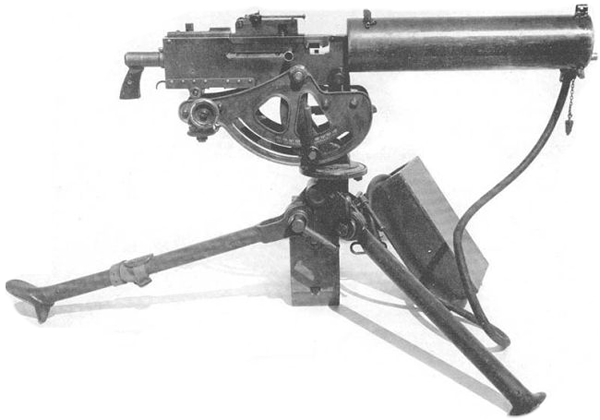

What Paige did have was discipline, physical toughness, and exceptional marksmanship. He became an expert with crew-served weapons, especially the M1917 Browning machine gun—a heavy, water-cooled weapon designed for sustained defensive fire.

That training would matter more than anyone could have imagined.

Guadalcanal: The Island That Decided the Pacific

By mid-1942, Guadalcanal had become the most important piece of ground in the Pacific. The Japanese were building an airfield that would threaten Allied supply routes to Australia. When U.S. Marines landed and captured it, they renamed it Henderson Field.

Japan responded with relentless counterattacks.

Night assaults. Jungle infiltrations. Mass infantry charges.

The goal was always the same: retake Henderson Field.

Coffin Corner

Paige’s machine-gun section was assigned to a ridge south of the airfield, a position Marines grimly called “Coffin Corner.” It was a natural avenue of approach for Japanese infantry—and a killing ground if properly defended.

Paige spent weeks preparing the position: clearing fields of fire, stockpiling ammunition, positioning guns to overlap.

On the night of October 25–26, 1942, the attack came.

When the Line Collapsed

More than 2,000 Japanese soldiers advanced through the darkness.

Paige commanded four machine guns and sixteen Marines.

Within hours, grenades, rifle fire, and hand-to-hand combat destroyed three gun positions. One by one, Paige’s Marines were killed or wounded. By 1:47 a.m., he was down to a single gun crew.

Minutes later, he was alone.

One Man, One Gun

The M1917 Browning weighed over 100 pounds with its tripod and water jacket. It fired .30-06 rounds at a sustained rate of 450 rounds per minute. Paige fired controlled bursts—five to seven rounds at a time—conserving ammunition and preventing the barrel from warping.

The water jacket boiled dry. The barrel glowed red, then white.

Paige refilled it with water from his canteen. The water flashed into steam.

He cleared jams under fire. He dove from grenades. He kept firing.

Bodies piled up twenty yards in front of his position.

The Last Belt

By 3:15 a.m., Paige had less than one ammunition belt left.

Japanese officers shouted. Another charge formed.

When the belt ran empty, Paige drew his pistol and fired into the charging soldiers, fully expecting to die.

Then he heard American voices behind him.

Reinforcements.

The Counterattack No One Expected

Instead of retreating, Paige did something almost unthinkable.

He disconnected the machine gun from its tripod, loaded the last rounds, and charged downhill—firing the weapon from the hip while leading a counterattack.

It was tactically insane.

It worked.

The Japanese assault collapsed. Survivors fled into the jungle. Henderson Field was safe.

Dawn at Coffin Corner

When daylight came, Marines counted more than 200 Japanese dead in front of Paige’s position alone. Fifteen Marines from his section were dead. Paige was the only survivor.

He made no speeches. He filed a factual report.

His commanding officer recommended him for the Medal of Honor.

Recognition and Legacy

In 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt presented Mitchell Paige with the Medal of Honor. Paige insisted that the real credit belonged to the Marines who died beside him.

He spent the rest of his career training others, never seeking fame.

He died quietly in 2003 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

The machine gun he used is preserved today—a standard weapon that became extraordinary in the hands of an extraordinary Marine.

Why Those Three Hours Mattered

History often turns on massive decisions and sweeping strategies.

Sometimes, it turns on one exhausted man behind a machine gun, refusing to let go.

Three hours. One Marine. One ridge.

Those hours helped decide Guadalcanal.

And Guadalcanal helped decide the war.