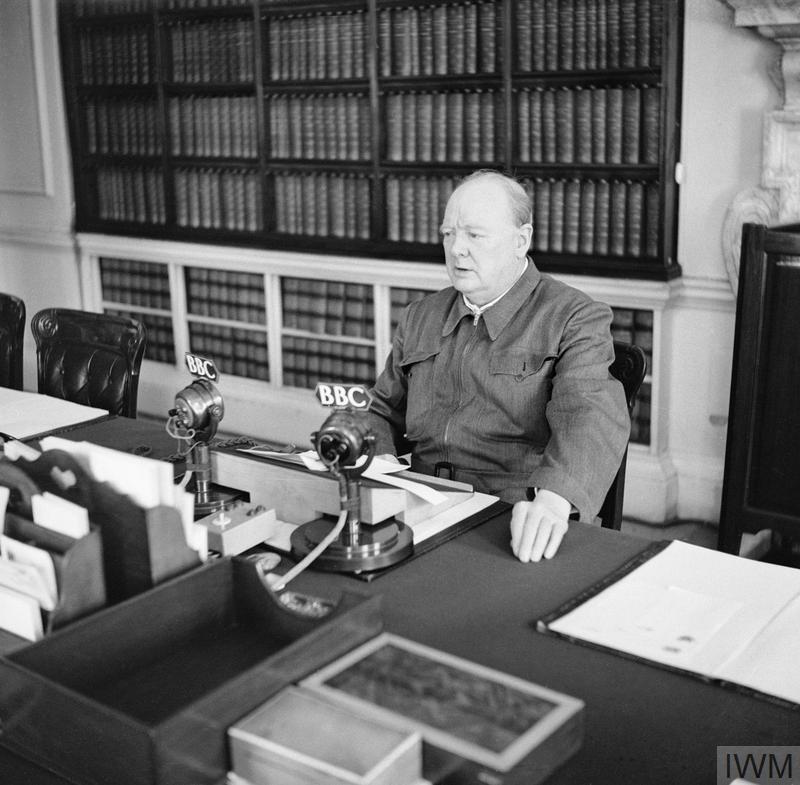

On the night of March 17, 1945, the war in Europe was almost over—and more fragile than it had ever been. Inside a quiet room at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force in Reims, Winston Churchill sat alone beneath a shaded lamp, cigar smoke drifting toward the ceiling. He was reading casualty reports, the final arithmetic of a war Britain had survived at immense cost. Outside, armies pressed east toward the Rhine and beyond. Inside, Churchill counted names.

Then the door opened without a knock.

His chief of staff entered with the stiffness of a man delivering bad news that could not wait. “Prime Minister,” he said, “we have a situation.”

Churchill looked up. He knew that tone. “Go on.”

“General George S. Patton has just called Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery ‘timid’—in front of forty war correspondents. The wires have it. The BBC has it.”

Churchill froze. The cigar stopped halfway to his mouth.

For five years the Allied coalition had survived blitz, defeat, rivalry, humiliation, and bloodshed. It had endured not because its leaders agreed, but because they restrained themselves when agreement was impossible. And now, six weeks before victory, one word—timid—threatened to unravel it.

The Comment That Lit the Fuse

Six hours earlier, in Koblenz, Patton stood before a crowd of journalists flushed with triumph. His Third Army had just crossed the Rhine at Oppenheim—Hitler’s last great natural barrier in the West. Where planners expected weeks of preparation and heavy losses, Patton’s men crossed in the night with a single regiment. Twelve casualties. The feat was breathtaking.

A reporter asked the question that everyone was thinking but few dared phrase directly: how did Patton’s lightning crossing compare to Montgomery’s carefully planned Operation Plunder, scheduled for the following week?

Patton smiled. Not warmly.

“I prefer aggressive action to timid planning,” he said. “That’s how you win wars.”

He never said Montgomery’s name. He didn’t need to.

Every correspondent knew exactly whom he meant. Within minutes, the quote was racing across Europe. Within an hour, it was in London. And within two, Montgomery’s headquarters was on the phone, demanding Patton’s immediate removal from command.

Churchill’s Nightmare

Churchill understood the danger instantly. Montgomery was not just a general; he was a national symbol. To millions of Britons, “Monty” was the man of El Alamein, the embodiment of British resilience after years of retreat. To allow a foreign commander—however brilliant—to mock him publicly was politically explosive.

Worse, it cut to the core of coalition warfare. British soldiers had learned caution the hard way. In 1940 and 1941, Britain had fought with limited resources, limited manpower, and the memory of near-annihilation. Careful planning was not timidity; it was survival.

Churchill read the transcript again. And again.

The numbers haunted him. Montgomery’s operation: 250,000 men, thousands of guns, weeks of preparation. Expected casualties: several thousand. Patton’s crossing: speed, surprise, audacity—and twelve dead.

Patton wasn’t wrong.

But being right did not make him safe.

Eisenhower in the Middle

The call to Dwight D. Eisenhower came quickly. Churchill did not shout. He did not need to.

“Dwight,” he said, “one of your generals has publicly insulted the most important British commander of this war. I need hardly explain the consequences.”

Eisenhower had been dreading this moment for months. He had spent more time managing Patton and Montgomery than planning operations. Both men were indispensable. Both men were unbearable.

“Prime Minister,” Eisenhower replied carefully, “Patton was answering a direct question about tactics. He didn’t name Montgomery.”

Churchill cut him off. “Everyone knew whom he meant. This is not about semantics. It’s about trust.”

There was a pause. Then Churchill’s tone softened. “I am not asking you to fire Patton. I am asking you to control him.”

Behind those words lay an unspoken threat: if Eisenhower failed, British political pressure could force Montgomery’s resignation—or worse, fracture the alliance in its final hour.

A Pattern, Not an Accident

That night, Churchill asked for everything. Every report. Every transcript. Every whisper of rivalry. What arrived the next morning was not a thin file—it was a thick one.

Patton calling Montgomery “overcautious” in December.

Patton joking that Montgomery wouldn’t attack without a 2-to-1 advantage.

Patton privately mocking British “tea breaks” and planning conferences.

This wasn’t a single slip. It was a campaign.

When Field Marshal Alan Brooke, Britain’s chief of the Imperial General Staff, arrived at Churchill’s office, he spoke bluntly. “Prime Minister, this cannot continue. Either Patton goes—or Montgomery does.”

Churchill stared at the map of Europe. He knew the truth: losing either man would weaken the final push into Germany. Losing both would be catastrophic.

The Summons

Eisenhower made his decision. He summoned both men to SHAEF headquarters on March 21, 1945.

The atmosphere was electric. Security was doubled. Staff officers whispered that if the meeting went badly, careers—and perhaps the alliance itself—would not survive.

Montgomery arrived immaculate, every medal polished. Patton arrived on time, boots gleaming, revolvers at his side. The room fell silent as the two men faced each other.

Then, unexpectedly, Patton extended his hand.

“Congratulations on your Rhine crossing, Field Marshal,” he said. “I hear it will be quite a spectacle.”

It was not an apology. But it was not an insult either.

The Confrontation

The meeting was brutal.

Montgomery accused Patton of undermining British authority. Patton shot back that Montgomery’s caution cost time and opportunity. Montgomery called Patton reckless. Patton replied that wars were won by killing the enemy faster than he could react.

Voices rose. Tempers flared.

Then Churchill stood.

He did not shout. He did not threaten. He did something far more dangerous to a man like Patton.

He spoke of history.

“General Patton,” Churchill said, “you are perhaps the finest attacking general in the American Army. Field Marshal Montgomery is the most methodical commander Britain possesses. These are not flaws. They are complementary strengths.”

Then he leaned closer.

“But if you cannot restrain your ego, you will not be remembered for crossing the Rhine. You will be remembered as the man who divided the alliance that won the war.”

Patton understood immediately. Legacy mattered to him more than rank, more than comfort, more even than command. Churchill had aimed at the only target Patton could not ignore: the judgment of posterity.

“I’ll issue the statement,” Patton said at last.

Aftermath

The apology came the next day—formal, precise, bloodless. Montgomery accepted it just as formally. The press moved on. The alliance held.

Operation Plunder launched days later and succeeded with fewer casualties than expected. Patton’s Third Army surged east. Together, caution and aggression crushed what remained of the Third Reich.

Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945.

What the Moment Revealed

This incident was never about a single word. It was about two philosophies of war—and two visions of legacy.

Patton believed speed saved lives by ending wars quickly. Montgomery believed preparation saved lives by preventing catastrophe. Both were right. Both were dangerous alone.

Churchill understood something neither general fully grasped: wars are not won by brilliance alone. They are won by alliances that survive their own heroes.

In that quiet room in Reims, with victory in sight and disaster just as close, one word nearly destroyed five years of sacrifice.

And one speech—never officially recorded—held it together just long enough to finish the war.

If you want, I can next:

• expand this to a full 3,000+ word long-form documentary script,

• rewrite it as a cinematic YouTube narration, or

• focus on who was “right” militarily—Patton or Montgomery—using postwar analysis.