“We Didn’t Know” — Why Patton Forced the Rich and Famous Germans to Face the Truth

The first thing that hit him was the smell.

It rolled toward the convoy like a physical thing, sliding in through the open jeep, thick and oily and wrong. George S. Patton had smelled death before—on battlefields in France, in the roasting deserts of North Africa, in the rubble of Sicilian towns—but this was different. This was not the sharp, metallic tang of fresh blood or the sour reek of unwashed men. This was older, heavier. It was decay that had been allowed to settle, to soak into the earth.

He felt it coat the back of his throat, felt his stomach lurch in violent protest.

The jeep slowed as they approached the gates, the barbed wire perimeter rising out of the peaceful German countryside like some obscene afterthought. The camp sat in a shallow clearing, ringed by dark fir trees that swayed gently in the April wind. From a distance, it might have been mistaken for a lumber yard or a work detail—a collection of low wooden barracks, watchtowers, and fences.

From up close, no one could make that mistake.

Patton climbed down from the jeep, his boots crunching on the gravel. For a moment he just stood there, his gloved hands resting on his hips, his jaw set hard. Behind him, his staff officers waited in silence. The Third Army had rolled through dozens of German towns by now; they had seen wreckage, dead civilians, desperate refugees. They had heard rumors of camps like this one. “Labor facilities,” the Germans called them. “Penal camps.” The words had always sounded thin, like paper barely covering something else.

Now, with that smell crawling into their lungs, the paper was gone.

Patton took a step forward.

The camp gate stood slightly askew, one side hanging from a twisted hinge where the fleeing guards had left it. The barbed wire sagged in places where it had been cut from the outside, American engineers clearing paths earlier that morning. The sign above the entrance bore the camp’s name—Ordruf—painted in neat, bureaucratic letters that made the whole thing seem even more obscene, as if murder could be run like a postal station.

“Sir?” one of his aides said quietly. “The path is clear.”

Patton nodded once and walked through the gate.

The smell grew stronger with every step. He tried to breathe through his mouth, but the air itself tasted wrong. His eyes watered, though whether from the stench or the sudden, fierce wind, he couldn’t say. He moved forward anyway, because that was what he did. His entire life had been about movement—cavalry charges, sweeping offensives, arrows on maps driving forward, forward, forward. Now the arrow pointed into hell.

The silence unnerved him.

In other places, war was loud. Artillery boomed, engines roared, men shouted. Even after the firing stopped, there was always sound—distant gunfire, the rumble of trucks, birds returning cautiously to blasted trees. But here… nothing. The camp lay in a hush so deep it felt wrong, as if even nature had decided this ground was not worthy of its usual noise.

He heard his own boots on the packed dirt, the soft creak of leather. He heard a man behind him cough sharply and then clamp his mouth shut as the smell hit him.

The first body lay near the gate.

At first glance, Patton thought it might be a bundle of old clothes, tossed aside in haste. Then the wind shifted, lifting a scrap of striped fabric, and he saw the hand. It was skeletal and gray, the skin stretched too tightly over the bones, fingers curled inward like the claws of a bird.

Patton stopped.

He had seen dead men by the thousands. He had stepped over corpses in trenches, ridden past them on horseback, watched them fall from tanks. He had grown almost accustomed to it. Death, in combat, had a kind of terrible dignity. A man who died charging an enemy position, who died with a rifle in his hand, was at least allowed the decency of having fought.

This man had died in a striped uniform, face turned toward the dirt, alone.

His knees nearly buckled. For an instant—a brief, shocking instant—the legendary George Patton, the fire-eating general who had demanded courage from everyone around him, thought he might actually faint. His stomach turned violently.

He took two quick steps to the side, away from his men, and doubled over.

The vomit came hard and fast, burning his throat, splattering on the dirt. The smell of his own sickness mingled with the camp’s stench, and for a moment he thought he might never be able to stand again. He braced one hand on his knee, squeezing his eyes shut.

No one spoke. His staff waited, frozen, pretending not to see.

Patton straightened.

His face was pale, his eyes hard. He took a handkerchief from his pocket, wiped his mouth, folded the cloth with meticulous care, and tucked it away again. He adjusted his helmet. When he turned back toward the camp, his jaw had set into that familiar granite line again.

“Let’s go,” he said.

They walked deeper into Ordruff.

The barracks loomed on either side, long buildings of rough wood. The doors stood open, some hanging crooked where they had been smashed in. Patton stepped into the first one, and his eyes, adjusted to the gray daylight, struggled to make sense of the dark interior.

Then shapes began to resolve.

Bunks stacked six-high lined the walls—crude shelves of planks with wisps of filthy straw. Each space was barely wide enough for a man to lie on his side, and yet there were signs that multiple bodies had slept in each slot: overlapping indentations, ragged blankets, the faint outline of where someone had clutched the wood in the night.

The smell was worse here, trapped under the low ceiling.

On the far bunk lay another body, this one so thin that for a moment Patton thought it was some kind of gruesome medical diagram. Every rib, every vertebra, every tendon seemed to be visible. The man’s eyes were open, staring at the ceiling, and Patton realized with a jolt that he wasn’t entirely sure whether the man was dead or not. His chest moved—or did it? A whisper, maybe.

“Christ,” muttered one of the officers behind him.

An Army doctor pushed past them, stepping quickly to the bunk. He pressed two fingers against the prisoner’s neck, his face bending close. Then he straightened.

“Alive,” he said hollowly. “Barely.”

The man’s eyes shifted, just slightly, toward Patton. They were enormous in his shrunken face, giving him an almost childlike look. There was no expression Patton could recognize—no fear, no hope, no gratitude. Just exhaustion so profound it seemed to erase everything else.

Patton didn’t move. He felt something inside him—some carefully constructed armor he had built over years of war—crack, just a little.

“Get him out of here,” he said quietly.

There were more barracks. More bodies. More of the living-who-were-almost-dead, stumbling out into the light with slow, uncertain steps, shielding their eyes, bones moving under skin like loose sticks inside a paper bag. They stared at the Americans with a kind of dazed, distant curiosity, as if they weren’t entirely convinced these new figures were real.

Patton forced himself to look at everything.

He walked the length of the compound, his boots passing gallows where men had been hanged for infractions as minor as stealing a potato peel. He inspected the primitive crematorium—a squat brick structure that looked unremarkable until you stood close enough to see the ash, the blackened interior, the scorched marks where flesh had stuck.

A young officer cleared his throat.

“Sir, the ledgers,” he said.

Patton stepped into a small administrative building near the center of the camp. Inside, away from the wind and the smell, it almost looked like any office anywhere in the world. A desk. A typewriter. Shelves for binders. Everything neat and labeled.

And on those shelves: records.

American soldiers had already pulled some of the books down, spreading them on the table. Patton picked one up. The pages were dense with careful handwriting and rubber stamps. Names, numbers, dates. Transfers. Deaths. Calorie rations. Work assignments.

His eyes drifted down a column. The entries marched in neat rows—a series of lives reduced to data points.

Next to some names was a single, neat notation: “Verstorben.” Deceased.

He flipped forward. The pages kept going. The handwriting changed sometimes, but the pattern was the same. Names. Numbers. Death.

This was not chaos, he thought. This was not the wild brutality of a battlefield. This was a system. Designed, built, and maintained with the same clinical precision with which Germany produced tanks and artillery.

His hand tightened around the edge of the ledger until his knuckles turned white.

Outside, one of his officers called him over to another building, this one larger, with a door that stuck hard before giving way. Inside, the air was cooler, the smell less immediate. For a second Patton thought it might be some sort of storage hut. Then his eyes adjusted.

Shoes.

Rows upon rows of them, stacked in piles that rose nearly to his shoulder. Men’s shoes, women’s shoes, children’s shoes. Some were scuffed and worn, others looked almost new. Someone, at some point, had taken the time to sort them by size and quality.

He stepped closer, reached out, and lifted a small brown leather pair from the top of the nearest pile. They fit in his hand easily, tiny scuffs on the toes. He stared at them for a long moment.

A child, he thought. Some mother had laced these up once, maybe kneeling in a doorway, telling the child to be careful, to hurry along. The child had probably squirmed and giggled. And now the shoes were here, in a neat pile among thousands, and the child was…

He put the shoes back, carefully.

“Sir,” an aide said, voice tight, “you might want to see this.”

They led him to a fenced-in area near the back of the camp.

It might have been almost comical, in any other context: a row of small cages, each with a metal label. Inside, a few animals paced nervously or lay curled in the corner—dogs, a fox, a pair of thin, ragged deer. There were feeding dishes, water buckets, even toys.

“The guards kept them as pets,” the officer said. “A sort of camp zoo, by the looks of it.”

Patton stared at the animals, then at the barracks behind him, then back again. His jaw clenched.

“They fed them,” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

“Regularly.”

“Yes, sir.”

He didn’t say anything more. He didn’t need to. The comparison hung in the air: animals cared for, prisoners starved.

Rage rose inside him, hot and pure, unlike anything he had felt even under fire. On a battlefield, men killed each other because they were ordered to, because they were afraid, because they wanted to live. It was ugly and savage, but there was a brutal logic to it. This—this was something else. This was the deliberate, thoughtful choice to feed animals and let human beings rot.

It was evening when he finally stepped back through the camp gates.

The sun sank behind the trees, throwing long shadows across the compound. Smoke from the nearby town’s chimneys mingled with the sour air of the camp, creating a gray haze. Patton walked back to his command tent without speaking. His staff parted silently to let him pass.

Inside, the tent felt suddenly too small. The camp seemed to cling to him—the smell, the sights—all lodged somewhere he couldn’t brush off with a handkerchief. He sat heavily at his field desk, took out his diary, and opened to a blank page.

For a long time, he just sat there, pen poised.

He had always written about war in a certain way. He favored clear words, direct statements, sometimes even a hint of romanticism about battle and courage. War, to him, was the ultimate proving ground—a test of character, of discipline, of will. He believed in the warrior’s code, in honor, in audacity.

Now he tried to put Ordruff into words, and found that language itself resisted

He wrote haltingly at first, describing the camp, the bodies, the living dead. The pen scratched across the paper, his hand trembling more than he would ever admit. He wrote that he had finally seen something that made every bullet fired, every bomb dropped, every life lost in this terrible war make sense. That all the sacrifice, all the pain, all the marches through mud and blood were justified if it meant stopping this.

Then he wrote something else, something that came not from the general, but from the man underneath the stars.

They must not be allowed to say they didn’t know.

He stared at the sentence for a long time, the ink still glistening. Outside, he could hear trucks shifting gears, men shouting orders, the usual sounds of an army on the move. Inside the tent, the air seemed very still.

Three miles away, the town of Ohrdruf prepared to light its lamps.

It was, by the standards of wartime Germany, a lucky place. The houses stood whole, their roofs intact, their windows unbroken. Small gardens already showed green shoots pushing through the soil. The main street, lined with shops, was worn but functional. The church steeple rose higher than anything else, an orderly white finger pointing toward the evening sky.

People there had lived through shortages, of course. There had been ration cards, long lines, the occasional air raid siren that sent them scurrying to their basements. But compared to cities like Hamburg or Dresden, they had been spared. Their children still played in the streets. Their Sunday services still drew crowds. Their wealthiest citizens still hosted small, tasteful gatherings where the crystal glasses clinked and the talk was of business and politics and the latest news from the front.

They had heard rumors, too. It was impossible not to.

Some claimed that just outside of town there was a camp where criminals were sent to be “re-educated.” Some said it was only a labor site, nothing more. A few, more honest or more haunted, admitted to themselves that they had heard the trains at night, the distant shouts, the gunshots that came oddly muffled through the forest.

Every so often, on a cold, still evening when the wind blew from the wrong direction, a thick, sour smoke had rolled across the town. People had closed their windows then, wrinkling their noses.

“What is that smell?” someone would ask.

“I don’t know,” another would reply quickly. “Probably just a factory.”

And then, almost as if they had rehearsed it, the conversation would move on.

In the mayor’s house, the radio played a German orchestra. The mayor himself sat in his study, a man in his fifties with a carefully groomed mustache and the tired, satisfied look of someone who had chosen the winning side early and profited from it. On the wall behind his desk hung his Nazi party membership certificate, framed. He had joined in 1933. He liked to tell visitors he had seen Hitler speak in person once.

The banker lived two streets over, in a handsome home with polished floors and thick carpets. He had handled the accounts when certain Jewish properties in town had been transferred to new owners—“abandoned assets,” the forms called them. It had been distasteful work, perhaps, but legal. Everything stamped, everything filed.

The factory owner’s house stood on a small hill, overlooking both the town and the not-so-distant tree line that hid the camp. From his upstairs window, on clear days, he could see the column of smoke that rose from behind the trees. He had never asked what they were burning. He had never walked closer to find out, even though some of the workers on his shop floor—odd, hollow-eyed men in striped scraps who spoke little German—came from that direction every morning, and vanished back there every night.

The doctor, respected and dignified, sipped his coffee on a small terrace, flipping through a medical journal. He had been asked, once or twice, to consult on certain “special cases” brought in by the SS—prisoners with injuries, prisoners whose bodies were wasting away. He had refused to ask too many questions.

The socialite laughed in a parlor filled with guests, her silk dress brushing the floor as she reached for a glass of wine. They said she hosted the best parties in Ohrdruf, that her table was always lavish—even in wartime—and her husband’s connections ensured they never lacked for good sausages or imported delicacies. Once, during a summer evening, a guest on her terrace had frowned and tilted his head toward the forest.

“Is that smoke from the camp?” he’d asked, half-whispering.

She had laughed and waved a jeweled hand. “Don’t be morbid,” she’d replied. “You spoil the mood.”

Now, as American artillery rumbled faintly in the distance, the town’s elite rehearsed three words in their heads, like a charm.

We didn’t know.

They said it silently as they folded their evening papers, as they checked their accounts, as they tucked their children into bed. They imagined the questions that might come when the Americans arrived, the accusations. And they pictured themselves lifting their hands, widening their eyes, and saying it: We didn’t know. It had a nice ring to it. It made them sound helpless, innocent, like victims themselves.

Back in the command tent, Patton’s pen moved again.

He had been a soldier long enough to understand that after a war comes a story. Nations rewrote their roles, minimized their guilt, magnified their heroism. Already, he could almost hear the future Germans explaining: It wasn’t us. It was Hitler. It was Himmler. It was the SS. A handful of fanatics. A small circle of madmen.

And what of the people who had cheered in stadiums, who had seized their neighbor’s shop keys, who had enjoyed the spoils? What of the professionals who had sat at desks and stamped forms, who had nodded solemnly at lectures on race and loyalty? What of the bankers and mayors and professors and priests?

They would all say: We didn’t know.

He set the pen down and stared at the canvas wall of the tent as if he could see through it, through the trees, through the darkening fields, all the way to the town’s tiled roofs. He imagined the mayor pouring himself a drink. The banker going over ledgers. The factory owner checking tonight’s output. The doctor washing his hands. The socialite smoothing her nightgown.

No, he thought. They will not say it. Not without facing what they did.

He stood, the decision forming not so much as a plan but as an instinctive response, the way he would see a gap in the enemy line and know he had to drive through it. If he left this camp as a pile of photographs and reports, then the story could still be twisted. People could claim that what happened here was the work of shadows, of men no longer alive to answer.

But if he brought the people who had lived three miles away, who had dined on full plates while their neighbors starved within earshot—if he made them walk through the camp, smell the smell, see the bodies—then their denial would crumble.

He sent for Eisenhower and Bradley.

The meeting was held in a commandeered farmhouse on the edge of town, the sort of tidy German dwelling that had once been the pride of its owners. Now maps and radios covered the kitchen table. A portrait of some long-dead ancestor watched from the wall as three of America’s most powerful generals conferred.

Eisenhower looked older than his fifty-four years that evening, the lines etched deeper around his eyes. He had already toured the camp himself, stepping over bodies just as Patton had, seeing enough to shake even his steady composure. Bradley sat slightly hunched, his hat in his hands, eyes fixed on the tabletop as if the wood grain might offer some answer.

Patton outlined his idea.

He spoke bluntly, his words clipped. He wanted the town’s prominent citizens—the mayor, the council, the business owners, the doctors, the clergy, every wealthy man and woman who had profited under the Nazi regime—to be brought to Ordruff. Not invited. Brought. Under guard if necessary. He wanted them to walk the paths he had walked, see the barracks, the crematorium, the piles of shoes. He wanted them to look into the eyes of the survivors.

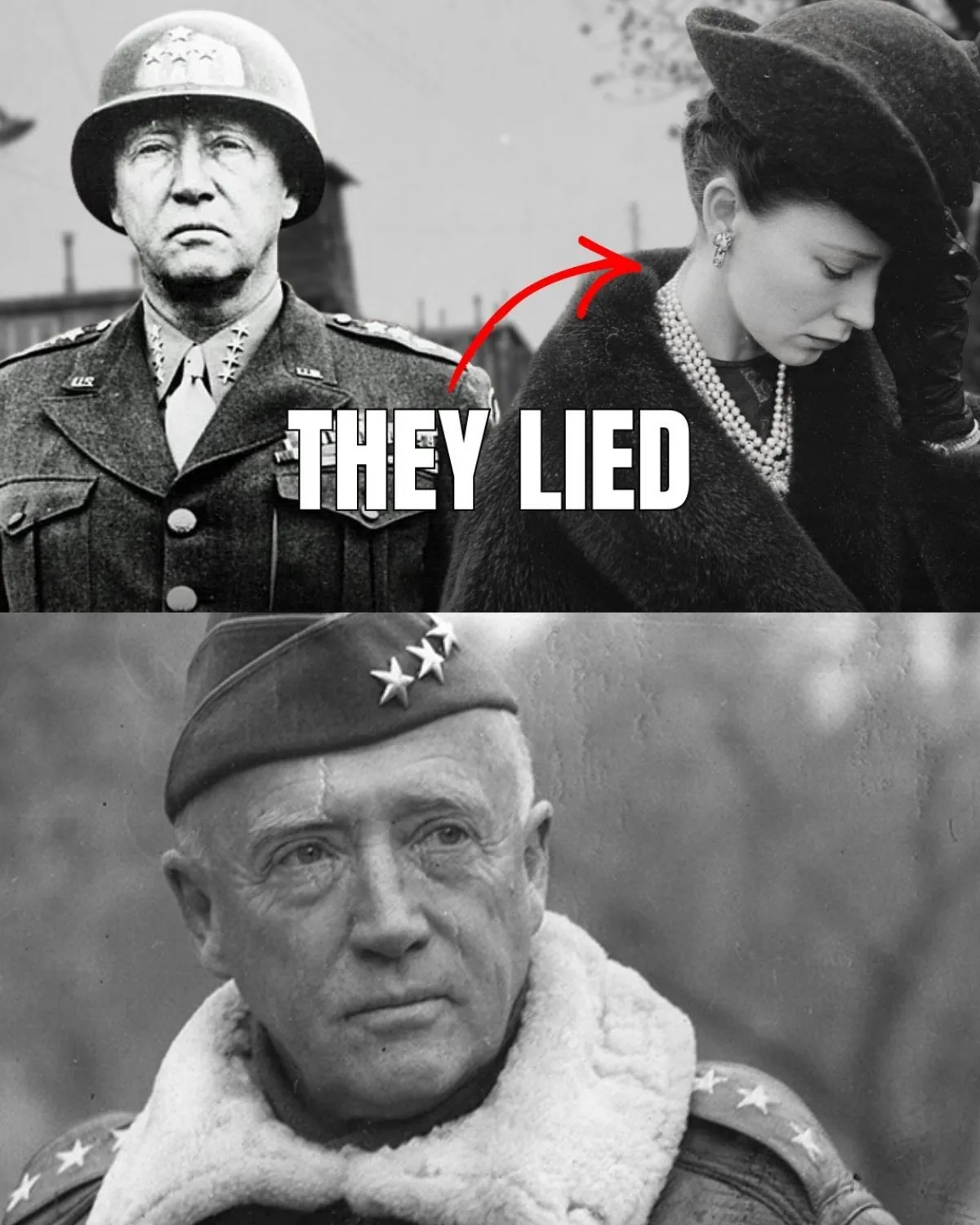

“We will photograph them,” he added. “Every last one of them. I want their faces on record. I want them recorded with that place behind them, so that when their grandchildren claim that their grandfathers never knew, we’ll have proof that they did.”

For a moment, the only sound in the room was the faint hiss of the radio and the ticking of a cuckoo clock on the wall.

Eisenhower ran a hand over his chin.

“You realize the implications,” he said at last.

Patton’s eyes flashed. “I realize that if we liberate these camps and then let every comfortable German pretend they were built by ghosts, then our boys died for nothing.”

“It’s not that simple,” Eisenhower replied. “We’re going to have to work with some of these people. We’ll need administrators, professionals, teachers. If we humiliate them like this, if we push them too hard, we might drive them into the arms of whatever’s left of the Nazi underground. Or the Communists.”

Bradley cleared his throat. “There are practical concerns too,” he said. “How do we select who goes? Where do we draw the line? And what happens if they refuse? Do we put rifles at their backs and herd them like cattle? That’s a picture the world might not like either.”

Patton’s jaw tightened.

“If they refuse,” he said, “we arrest them. Not because they’re refusing a tour. Because anyone who refuses to see that place is telling us something about their guilt.”

He leaned forward, his hands flat on the table.

“These people, Ike—they’re not peasants. They’re not illiterate farmers who never saw a newspaper. These are the men who ran the banks, the factories, the schools. The women who wore fur coats taken from deported families and pretended not to know where they came from. They have influence. They set the tone. If we let them slip away behind some lie about ignorance, then in ten years they’ll be sitting in the same positions, telling everyone that they too were victims. I won’t have it.”

Eisenhower looked at Bradley. Bradley looked back, his expression grim.

In the end, Eisenhower nodded slowly.

“All right,” he said. “We do it. But we do it carefully. This isn’t revenge, George. We’re not staging a spectacle for our own satisfaction. This has to be documented, controlled. It has to mean something beyond today.”

“It will,” Patton said.

He walked out of the farmhouse into the cold night, feeling the weight of the decision settle on his shoulders like a new kind of armor.

The next forty-eight hours were a blur of orders and lists.

Military police officers moved through Ohrdruf with folders and notepads, questioning townspeople, cross-checking party membership records, business licenses, property registers. They weren’t interested in the old woman who ran a vegetable stall, or the boy who delivered coal. Patton’s directive was specific: find the elite.

The mayor’s name was on every list. His membership card in the Nazi Party had come with certain privileges, and those privileges had left paper trails. The banker appeared next, his signature on documents approving the transfer of confiscated Jewish assets. The factory owner had contracts with the SS for “labor,” his profits swelling even as the war turned against Germany.

The doctor’s name surfaced in connection with certain “research projects” callously described in clinical terms. The schoolmaster had been photographed giving a speech to the Hitler Youth, his face stern as he urged patriotism and vigilance against “enemies of the people.” The Protestant minister’s church had hosted rallies and prayer services “for the Führer and the Fatherland.”

The list grew.

By the end of the second day, more than a thousand names filled the pages—men and women who had not merely survived under Nazi rule, but thrived. Their wealth, their memberships, their public roles all testified to their position in the system.

Notices went up around town, printed in German and posted on walls, on doors, in the market square:

ALL PROMINENT CITIZENS OF OHRDRUF

ARE HEREBY ORDERED TO REPORT

TO THE TOWN SQUARE AT 0800 HOURS

FOR INSPECTION AND INSTRUCTION.

FAILURE TO APPEAR WILL RESULT IN ARREST.

The word spread even faster than the paper.

That night, in the town’s handsome houses, conversations that had once been about shortages and gossip shifted into something thinner, more brittle.

In the mayor’s study, his wife watched as he reread the notice, his fingers tapping restlessly against the paper.

“What do you think they want?” she asked.

“A show,” he muttered. “The Americans are angry. They’ve seen… things.” He didn’t say the word “camp.” She noticed. She also didn’t say it.

“Will you go?” she asked.

He shot her a sharp, almost offended look. “Of course I’ll go. I’m the mayor.”

Two streets over, the banker’s wife set the notice on the dining table between the silver candlesticks.

“They can’t blame us for all of this,” she said, her voice trembling just a little. “We’re just citizens. We never knew what was really happening.”

Her husband stared at the folded sheet.

“We did what the law required,” he said. “We followed orders. We obeyed the government. That’s all anyone can ask.” He sounded as though he were trying to convince himself as much as her.

In the factory on the hill, the owner paced his office, looking out the window toward the dark smudge of the forest.

“This is bad,” he said to his foreman. “The Americans will look for someone to blame. They will want scapegoats. They always do.”

The foreman nodded, eyes down. He had seen the striped figures on the assembly line, the way they swayed with exhaustion, the way they were replaced without fuss when one failed. He said nothing.

The doctor opened a bottle of schnapps and drank straight from the neck. He had gone to university, studied Hippocrates, sworn to “do no harm.” He had also signed forms rejecting care for certain prisoners, their conditions deemed “beyond useful intervention.”

He thought of those forms now.

Across town, the socialite sat at her vanity, carefully removing her jewelry. She paused, her hand hovering over a pair of pearl earrings.

“I’ve heard,” she said quietly to her sister, who sat on the bed behind her, “that the Americans have found… terrible things near here.”

Her sister shifted uneasily. “Those are just stories,” she said. “Exaggerations. The British spread lies like that in the last war too. It’s all propaganda.”

The socialite looked at her reflection in the mirror. For a fleeting second, she thought she saw something behind her own eyes—a flicker of something dark, some memory of the smoke, the smell on those still nights. She blinked it away.

“We didn’t know,” she whispered to her own face. “We didn’t know.”

But some people did not sleep that night.

In the smallest houses, on the poorest streets, there were those who had heard more than rumors. A woman whose brother had worked as a guard, drinking himself into stupors when he came home on leave. A janitor at the train station who had seen the packed cattle cars, who had heard the muffled cries.

They lay in their beds, staring at the ceiling, listening to the town breathe. They had never had the luxury of pretending not to notice. But no one was asking them to report in the morning. They had no invitations to judgment.

As dawn crept gray and thin over the rooftops, the town square filled.

They came in suits and overcoats, in fur-lined collars and polished shoes. The mayor arrived in his formal coat, his badge of office pinned at the lapel. The banker wore a carefully knotted tie. The factory owner’s heavy wool coat looked almost new. The doctor carried his leather bag, as if he might be called on to tend someone. The minister had his collar. The socialite wore a fur coat that had once belonged to a Jewish woman who never returned.

They clustered together in small knots, speaking in low voices that died quickly whenever an American soldier passed. Some looked angry, their mouths pinched. Others looked wary, eyes darting toward the surrounding buildings as if seeking a way out.

Around them, American troops stood with rifles slung, helmets gleaming in the weak sun.

“Quiet down,” one of the MPs barked in rough German. “Silence!”

Patton watched from the steps of a commandeered building at the edge of the square. From here, the mass of them looked like any crowd he’d seen in Europe—well-dressed, well-fed people, the picture of respectable civilization.

Three miles away, in Ordruff, the bodies still lay on the ground.

At precisely 08:30, the march began.

The civilians were arranged in lines, ten across, and ordered to walk. Some tried to maintain their dignity, heads high, steps measured. Others stumbled almost at once, unused to the presence of armed soldiers so close behind. A few wept quietly without obvious reason, the tears simply sliding down their cheeks.

The road from Ohrdruf to the camp wound gently through fields and patches of forest. Under other circumstances, it might have been a pleasant walk in the spring air. The wind carried the faint smell of turned earth, of grass just beginning to green.

But as they approached the tree line, another smell pushed forward, shouldering aside the fresher scents.

It was subtle at first, a sourness that made some of the women wrinkle their noses, some of the men swallow hard. Just smoke, they told themselves. There’s a factory nearby. Perhaps a farm burns its rubbish.

With every step, it grew stronger. A few of the people in the lines slowed, glancing uneasily at one another. The socialite pressed a handkerchief to her face. The banker’s wife took her husband’s arm, fingers digging into the fabric.

“Was ist das?” she whispered.

He didn’t answer.

The trees thinned. The camp fences came into view.

Some of them had never truly looked at the camp before. They had seen glimpses from the train, distant guard towers through gaps in the forest, but had always turned their eyes away, focusing on something else—the sky, a conversation, a newspaper. Now there was nothing else to look at.

The watchtowers rose stark against the pale sky. The barbed wire glinted faintly. The gate, bent at one hinge, yawned open.

The smell was undeniable now. Thick. Sweet. Rotting.

Someone gagged in the back of the column.

Patton stood by the gate as they approached. He wore his usual riding boots, his helmet firmly set, his pistols at his belt. His face, carved in stone, gave nothing away. As the first line drew even with him, the mayor shifted slightly, as if expecting some speech, some explanation.

Patton said nothing.

He simply raised one gloved hand and gestured toward the entrance.

The tour began.

They were led along the same path the American soldiers had walked days before. But now, instead of a handful of officers and enlisted men accustomed to blood and horror, the paths were crowded with citizens who had spent the war in offices, in parlors, in comfortable pews.

At the first barracks, a soldier pushed the door fully open and stood aside.

“Gehen Sie hinein,” he said. “Go in.”

The mayor hesitated. The man behind him bumped slightly into his back. From inside the barracks came the heavy, still air of enclosed suffering. After a heartbeat, he stepped forward.

The interior was dark, eyes needing a moment to adjust. Then the lines of bunks emerged, stretching into the shadows. Straw. Filth. Stains. The memory of thousands of nights, of men stacked like firewood.

Someone near the front made a choking sound.

A woman in a fur coat reached blindly for the doorframe, her gloved fingers scraping the wood. “No,” she whispered. “No. This can’t be…”

On the middle bunk, a body lay twisted as if in mid-motion, the lips pulled back from the teeth in a frozen grimace. The banker stared at it, his own lips shaking. He seemed to want to look away, to force his head to turn, but couldn’t.

The banker’s wife, standing just behind him, clapped a trembling hand over her mouth. She had once written a letter to a relative in Dresden, describing with some irritation the odor that occasionally drifted across town. “They burn trash somewhere near here,” she had written. “It is unpleasant.”

Now she understood what had actually burned.

As they moved on, the American soldiers guided them to another barracks. This one contained not the dead, but the living.

The survivors had been washed and given blankets where possible, but nothing could disguise the angles of their bones, the grotesque swell of joints, the hollows where flesh should have been. They stood in clusters, watching the newcomers as if from another planet.

For a moment, the two groups simply stared at one another—fat and thin, clean and filthy, healthy and broken. The distance between them was only a few feet. It might as well have been a canyon.

One of the survivors, a man who had once been a schoolteacher in a small town far from here, saw a face in the crowd he recognized.

The schoolmaster from Ohrdruf stood near the front, his posture stiff, his hat clutched in his hands. Years ago, before the war, the two had attended a regional teachers’ conference together. They had shared coffee, talked about curriculum, discussed new methods of discipline. Later, the man from Ohrdruf had written enthusiastic letters about the “renewal” of German youth under National Socialism.

The prisoner stepped forward, his blanket slipping slightly from his shoulders. His voice, when he spoke, was ragged but clear.

“I know you,” he said in German.

The schoolmaster flinched.

“I saw you,” the prisoner went on. “At the station. When they brought us in.” His eyes were fixed, unblinking. “You stood on the platform. I looked at you. I remember thinking, ‘He is a teacher. Teachers help people.’ I thought you might… do something.”

The schoolmaster’s lips moved. “I—You must be mistaken,” he stammered. “I don’t—”

The prisoner shook his head slowly.

“You saw,” he said. “You looked at me. Then you turned away.”

Silence settled around them like dust.

The schoolmaster tried to meet the eyes of some of his fellow townspeople, to find support, but saw only horror and something worse: knowledge that they might have done the same.

They moved on.

In another section of the camp, they were shown the stacking grounds where bodies had been piled. The smell here was almost unbearable, the air heavy and still, as if reluctant to move over the dead. Flies buzzed in dense, lazy clouds.

Bodies lay in heaps, limbs stiffened, faces turned upward or jammed awkwardly against another’s shoulder. They were all ages—some old, some young. For the first time, a woman in the group screamed.

Her scream was high and thin at first, then rose into something stranger, half-laughing, half-howling. She clutched at her fur collar as if it might choke her, her eyes huge.

“Stop,” she gasped, though no one was speaking. “Stop. Please. Don’t show us this. I didn’t know, I didn’t—”

Her voice broke.

The American soldier nearest to her did not look away. He had lost friends in the Ardennes, had watched men bleed out in snow. He felt no pity for her fur coat.

“Keep walking, ma’am,” he said in halting German.

She took a step. Then another. Her laughter dissolved into sobs.

They were taken to the crematorium.

The ovens sat squat and solid, iron doors streaked with soot. A thin line of ash marked the floor in front of one, as if something had been spilled in haste. An American officer spoke, his voice flat.

“Here,” he said, “they burned the bodies. They kept records of how many per day. They calculated how much fuel they needed. It was efficient, they say.”

He gestured toward a small table nearby, where documents were laid out: plans, schedules, neat charts.

One of the wealthy women—that same socialite whose parties had once been the talk of the town—stared at the oven’s open mouth. Her mind, struggling to protect itself, grabbed at the absurd. It looked almost like an oversized bread oven, she thought wildly. Like something in a bakery.

Then, unbidden, she imagined small shoes lying just beyond the metal lip.

A sound tore out of her, startling even herself. She began to laugh—not with humor, but with some hysterical, jagged thing that seemed to claw its way out of her chest. The laughter bounced off the brick walls, high and shrill.

An American soldier moved toward her. For a moment he thought she was mocking the dead. Then he saw her eyes—wild, unfocused, brimming with tears.

She continued to laugh and cry at once, her body shaking. Finally, her knees gave way and she crumpled to the ground. Two soldiers lifted her under the arms, carrying her toward the exit as her laughter twisted into long, keening wails.

The doctor stood apart from the others, staring at a makeshift medical station in another building.

A survivor who had been forced to assist there pointed to a stained table, his voice empty as he described what had happened: injections given not to heal but to harm, wounds left untreated to “observe progression,” medicines deliberately withheld.

“We could have saved some,” the survivor said. “With just a little… care.” His thin hand hovered over a cracked bottle that had once contained painkillers. “But the camp doctor said it was… unnecessary. He wrote everything down. For science.”

The doctor from town listened, his face drained of color.

“I took an oath,” he murmured in German, barely audible.

The American translator leaned in. “What did he say?”

The translator’s English was quiet. “He says he took an oath to do no harm. That they all did. And he asks: what happened to them?”

The doctor’s mind raced backward, past the years of war, past the slogans and rallies, to a day when he had stood in a lecture hall in a clean white coat, repeating Latin words after his professor. He had felt then that he was joining something noble.

What happened?

At the edge of the camp grounds, under a cold gray sky, stood a pile of shoes.

They had moved some of them outside for the tour, sensing somehow that this would be the thing that pierced even the thickest armor of denial. The shoes lay in a mound of leather and laces, some cracked, some still bearing traces of polish. Among the adult sizes were tiny ones—small boots, delicate slippers, the kind of shoes children wore on Sundays.

The mayor stood before this pile.

He had made it almost the entire tour with his back straight, his expression carefully composed. Inside, he had been shaking, but he had told himself that a man of his position must not break in front of his citizens. He had nodded solemnly, had murmured “Wie schrecklich” at appropriate moments.

Now, faced with this mound of shoes, something inside him finally gave way.

He saw in the tiny pairs not just anonymous children, but faces from his own town. The little boy who had sat in the front pew at church, whose family had “vacated” their house one night, never to return. The girl who had sold flowers on the corner, whose mother had begged the mayor to intervene when the police came to take them. He had told her there was nothing he could do, that it was out of his hands.

He had signed papers turning over their property.

He fell to his knees.

His hat rolled off onto the dirt, unnoticed. His hands, which had once shaken confidently with ministers and party officials, now hung limp at his sides. His lips moved, but no sound came. Perhaps he prayed. Perhaps he tried to form the words We didn’t know and found that they dissolved in his mouth.

An American officer approached, a camera slung over his shoulder. He stood a few feet away and raised it.

“Ask him,” Patton said quietly, nodding toward the mayor, “if he still claims he didn’t know.”

The translator stepped forward, speaking in German.

“Do you still say you knew nothing?” he asked.

The mayor’s shoulders jerked as the words reached him. He didn’t look up. He stared fixedly at a single tiny shoe near his knees, its strap broken, its buckle dull.

He did not answer.

The silence stretched.

The camera shutter clicked.

The tour lasted three hours.

By the time they were led back to the camp gates, dawn’s gray had given way to the washed-out light of late morning. The line of civilians moved slowly now, as if every step was an effort. Some walked in a daze, their eyes fixed on nothing. Others wept openly, tears leaving white tracks on faces streaked with dust and sweat. A few looked angry—not at what they had seen, but at being forced to see it.

As they began the walk back to town, few words were spoken.

A woman behind the banker whispered, again and again, “It’s not our fault… it’s not our fault…” though she did not explain whose fault it was. The factory owner walked with his head down, hands trembling. He remembered the cheap labor that had appeared at his factory gates one winter morning, the way he’d signed the paperwork with relief, calculating how much he’d save.

The doctor clutched his bag so tightly his knuckles stood out. In his mind, the morgue and the infirmary at the camp overlapped with his own practice—two worlds that he had kept fiercely separate now colliding.

The socialite’s fur, matted with dirt after her collapse at the crematorium, hung askew on her shoulders. Her laughter had long since faded into a thin, continuous sobbing that came and went like hiccups.

Patton watched them go.

He did not feel satisfaction. There was no victory in this. Only a grim sense that something necessary had begun—a reckoning, perhaps, or at least the denial of a future lie.

By the end of the day, three of the most important names on that list were dead.

The mayor’s secretary found him hanging in his office, the rope tied with careful precision. His desk was neat, papers stacked in orderly piles. On top of one stack lay a note written in a tight, controlled hand. It did not claim innocence. It did not ask forgiveness. It simply said that he could not live with what he had seen.

The banker’s wife discovered him in his study, a pistol still in his slack hand, his head slumped forward on the desk blotter. Next to him lay ledgers showing profits climbing year after year, even as the war consumed more and more lives. He had balanced those columns carefully. Now the numbers stared up at him like accusations.

The socialite died alone in her bathroom, a bottle of pills spilled beside her. Her hands, which had once adorned themselves with jewels, now clutched the edge of the sink as if she had tried to hold on at the last moment. In her bedroom the wardrobe stood open, dresses hanging in neat rows. A fur coat with a faint, lingering smell of camp smoke lay crumpled on the floor.

Patton ordered photographs.

Not out of cruelty, but out of the same harsh logic that had compelled him to drag them to the camp. There would be no romantic stories of tragic Germans “unable to bear the horrors that others committed.” Their suicides would be understood for what they were: silent confessions from people who had benefited too long from pretending not to know.

In the days that followed, Patton wrote more.

His diary from that period read not like a general’s campaign journal, but like the notes of a man grappling with morality itself. He had spent decades studying battles, tactics, leadership. He knew how to move men across a map, how to predict an enemy’s next move. But Ordruff had taught him something no textbook covered: how ordinary people, especially those with education and comfort, could become the lubricants in a machine of mass murder.

He rejected entirely the idea that the German people were simply victims of a mad clique of leaders.

Hitler had not seized power in a vacuum. He had been cheered into office, his speeches amplified by newspapers, his ideas legitimized by academics. Industrialists had funded his rise, seeing profit in rearmament and plunder. Lawyers had rewritten laws to exclude certain citizens from protection. Teachers had drilled ideology into children’s heads. Priests had offered blessings for troops marching under the swastika. Judges had enforced racial decrees with solemn faces. Police officers had knocked on doors at night.

Without them, the camps could not have existed.

Patton’s anger settled most heavily on the elite.

He understood class and influence well. He had been born into privilege himself, raised in a world of riding schools and private tutors. He knew that those at the top of a society set its moral tone. They had freedom others did not. They could read foreign newspapers, access information, travel. They could choose to speak up or to remain silent.

The poor had excuses, of a sort. Their lives were consumed by survival. Many of them had little education, little access to anything but the propaganda handed to them. But the mayor? The banker? The factory owner? The doctor? The socialite? These people had chosen comfort over conscience. They had accepted promotions, contracts, party positions. They had smiled as their fortunes grew, never asking too loudly why certain houses became vacant, why certain neighbors vanished.

This was why he had insisted on bringing them—not the entire town, not yet, but the ones who had benefited most.

He knew that in the years ahead, as the rubble was cleared and new governments formed, there would be a powerful urge to narrow the circle of guilt. To say that only a few monsters had done this. To separate “Nazis” from “ordinary Germans” as if the categories were simple and clean.

He wanted the record to show that the most respectable citizens had walked past piles of shoes and rows of corpses, that their faces had crumpled and their alibis had withered.

Word of what he had done spread quickly.

Eisenhower, convinced by what he had seen at Ordruff and by Patton’s report, ordered similar tours near other camps. At Buchenwald, citizens of Weimar—custodians of Goethe and Schiller, proud of their city’s cultural heritage—were marched through barbed wire and past bodies. At Dachau, well-to-do residents of Munich’s suburbs were brought to see what their polite silence had enabled. In the British zone, at Bergen-Belsen, local Germans were forced not only to see the dead, but to help bury them, their hands grasping the same emaciated limbs they had once managed not to notice.

Everywhere, the pattern held.

The ones who had most loudly claimed ignorance were the ones whose lives had most clearly benefited from the regime. They had lived in houses taken from deported families, worn clothes from looted shops, worked at desks funded by stolen money. They had sat in churches and nodded along as sermons praised the Fatherland. They had eaten meat while others ate nothing.

Patton saw in all of this a larger lesson about evil.

It was easy, he realized, to imagine that great crimes were committed by obviously monstrous men—by mad dictators screaming from balconies, by sadistic guards with whips. But the truth was more disturbing. The machine required engineers and accountants and lawyers and yes, even charming hostesses with perfumed hair.

The most terrifying thing about Ordruff was not that it had been staffed by a few brutal SS men. It was that its existence had been known, in shadows and fragments, by thousands who chose each day not to walk three miles into the forest and ask, “What is that smell?”

He thought about his own country.

He thought about the power of wealth, of status, of being able to look away. And he wondered—though he did not write it down—what evils might one day be excused, in other lands, with the same three words.

We didn’t know.

In the weeks after the war ended, as trials began and testimonies were taken, those photographs from Ordruff would sit in files, in archives, in newspapers. Some would be shown in courtrooms, held up before men who tried to claim they had been powerless cogs. Some would be printed in magazines,, forcing readers far from Germany to confront images of corpses and of well-dressed townspeople staring at them with shattered faces.

In a few of those photographs, somewhere near the center, a man in a formal coat knelt in front of a pile of children’s shoes, his head bowed.

He had once rehearsed, in his tidy office, the words “We didn’t know.”

After Ordruff, he never said them again.