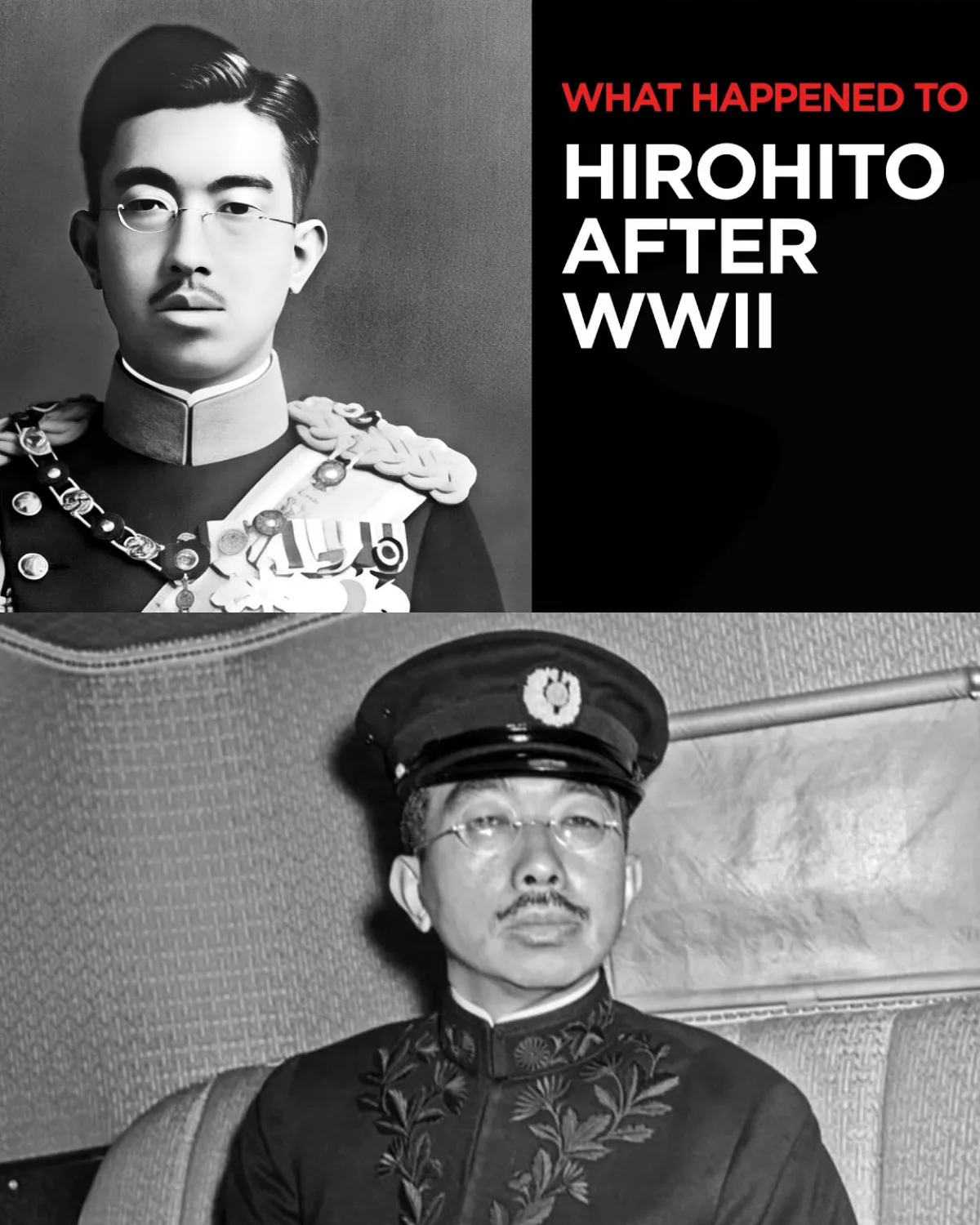

What Happened to Hirohito After World War II?

From “Living God” to Occupied Monarch**

On August 15, 1945, the heat lay heavy over Tokyo like a suffocating blanket, pressing down on a city exhausted and slowly smothered beneath its own ruins. The air was thick with dust and the acrid smell of charred wood. In the fortified basement of the Imperial Library, where courtiers had spent a sleepless night in near-feral tension, the emperor’s recorded message—cut onto fragile acetate discs—was prepared for broadcast to a nation that no longer existed in any recognizable form.

At noon, a crackling voice poured from battered loudspeakers across Japan. Its tone was so distant and unreal that many listeners struggled to believe it belonged to a human being—let alone the man they had worshiped as a living god. The archaic language of the imperial court drifted over the population. Few understood every word, but all grasped the terrible truth beneath the ornate phrasing.

Japan had lost the war.

For Hirohito, then fifty-four years old and raised within the sealed world of imperial ritual, the broadcast marked the end of an era that had defined his entire existence. The war had been fought in his name. His portrait had been carried into battle like a sacred standard. And now, the very voice that once sustained a national myth was extinguishing it. He never uttered the word surrender.

Instead, he spoke of how “the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage.” It was a tragic final act—a coded epilogue to national catastrophe. What followed was a silence deeper than the message itself. The imperial palace, built on centuries of reverence and mystery, became the eye of a storm.

Ministers, generals, and courtiers waited for the next directive from a sovereign who had just dismantled the ideological spine of his own regime. Beneath his calm exterior, even Hirohito could not yet articulate who he would be in the postwar world. His authority endured in name alone—and even that was about to be challenged by the victorious Allies preparing an occupation unprecedented in scale.

Days later, Douglas MacArthur arrived at Atsugi Airfield with the theatrical presence for which he was famous. The future of Japan lay within his power. But the most consequential question of the early occupation had already crystallized:

What should be done with the emperor?

Hirohito was not merely a defeated monarch. He was the embodiment of Japan’s wartime mobilization—the center of a political religion that had driven the nation into its darkest chapters. In the United States, many believed he should be tried as a war criminal. Some demanded his execution. The Soviet Union eagerly supported this view.

Yet the Americans on the ground in Tokyo saw the matter differently. General Bonner Fellers, MacArthur’s close adviser, concluded that the emperor was indispensable to the success of the occupation. Millions of Japanese soldiers were still scattered across Asia and the Pacific, many prepared to continue fighting. Only an imperial command could compel them to lay down their arms without further bloodshed.

Humiliating or executing the emperor, Fellers argued, would shatter what little order remained and plunge Japan into chaos.

Meanwhile, Hirohito drifted through the first days after surrender in a state of suspended animation. He continued imperial duties while absorbing the collapse of a civilization centered entirely around him. Within palace corridors, advisers debated whether he should abdicate. Some believed abdication would symbolize repentance. Others feared it would be seen as an admission of guilt.

Hirohito listened, nodded, and withheld judgment. As so often before, his silence functioned as a form of power. But the world beyond the palace walls was moving faster than imperial deliberation could match.

The Allied occupation was not merely military—it was ideological reconstruction. A system that fused divinity, nationalism, and militarism was being dismantled piece by piece. At its center stood Hirohito, a man who had been the national war leader and was now expected to become the guarantor of a peaceful transition.

On September 27, 1945, Hirohito met MacArthur at the Dai-Ichi Life Insurance Building. The symbolism was devastatingly precise. MacArthur appeared in an open-collared military shirt, hands on hips. Hirohito stood beside him in formal attire, small and rigid. The photograph shocked Japan.

For the first time in history, the emperor was shown standing next to another man—visibly subordinate. His aura of divinity evaporated in a single image.

Yet Hirohito did not falter. During the meeting, he reportedly offered to take full responsibility for the war. The gesture stunned MacArthur and convinced him that the emperor could be relied upon to stabilize Japan. From that moment, the machinery of immunity went into motion. Hirohito would be shielded from prosecution at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

In exchange, the emperor would accept a radical transformation.

On January 1, 1946, he issued what became known as the Humanity Declaration. Hirohito announced that the bond between himself and the Japanese people did not rest on divine origin, but on mutual trust and affection. He renounced his status as a living god.

For many Japanese, the declaration was a shock that shattered a core pillar of identity. Yet the text was carefully crafted. Hirohito denied divinity, but did not reject the mythological continuity of the imperial line. Americans believed they had secularized the throne. Japanese conservatives believed they had preserved it. Both interpretations served their purposes.

From that moment, Hirohito began what might be called his second life.

He toured the country, walking among ruins, standing in devastated Hiroshima, bowing awkwardly before ordinary citizens. The image of a former deity moving among mortals reshaped Japan’s psychological landscape. Resistance was minimal. The nation did not fracture.

In later years, Hirohito withdrew into the palace and devoted himself to marine biology, studying hydroids and microscopic sea life with the focus of a professional scientist. This new persona—a monarch absorbed in empirical study rather than command—helped Japan rebrand itself as peaceful and modern.

Yet the question of wartime responsibility never disappeared. When Hirohito died on January 7, 1989, the debate resurfaced. Was he a willing architect of war, or a prisoner of the system he symbolized?

History has never delivered a final verdict.

Hirohito’s fate after 1945 mirrored the fate of Japan itself:

reconstruction, reinvention, and a carefully managed relationship with an unresolved past.