The Spirits in the Rifle

A Cinematic–Historical Reconstruction of Francis Pegahmagabow and the Mystery That Survived the Great War

In the shattered landscapes of the First World War, where men and machines collided in an industrialized apocalypse, history recorded its victories in miles gained and bodies counted. Yet some stories resisted reduction. Some refused to fit neatly into ledgers and after-action reports. Among them is the story of Francis Pegahmagabow, an Indigenous soldier whose legacy exists in the uneasy space between documented fact and enduring legend.

This is not merely the story of a sniper.

It is the story of a worldview entering a modern war—and leaving investigators, historians, and weapons experts unsettled long after the guns fell silent.

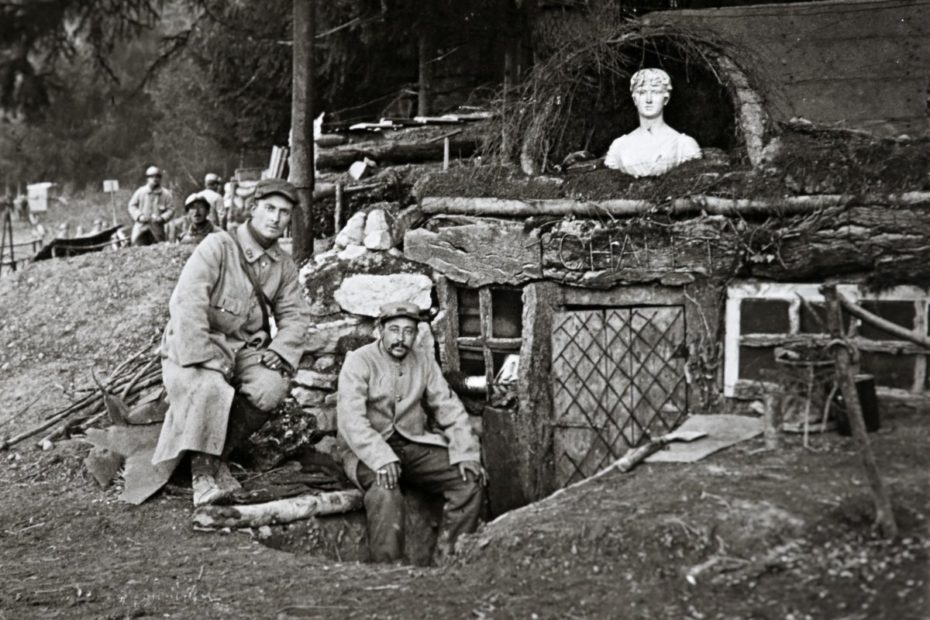

I. The Mud That Swallowed Empires

Between 1914 and 1918, Western Europe became a graveyard measured in trenches. The Western Front stretched like an open wound from the North Sea to Switzerland, a maze of mud-filled ditches where soldiers lived, froze, and died within yards of their enemies. Shellfire pulverized villages into dust. Rain turned the earth into a sucking morass that swallowed men whole.

In this environment, survival demanded more than courage. It demanded patience, restraint, and an almost supernatural ability to read terrain and timing. Most soldiers endured. Few mastered it.

Francis Pegahmagabow did more than master it.

He disappeared into it.

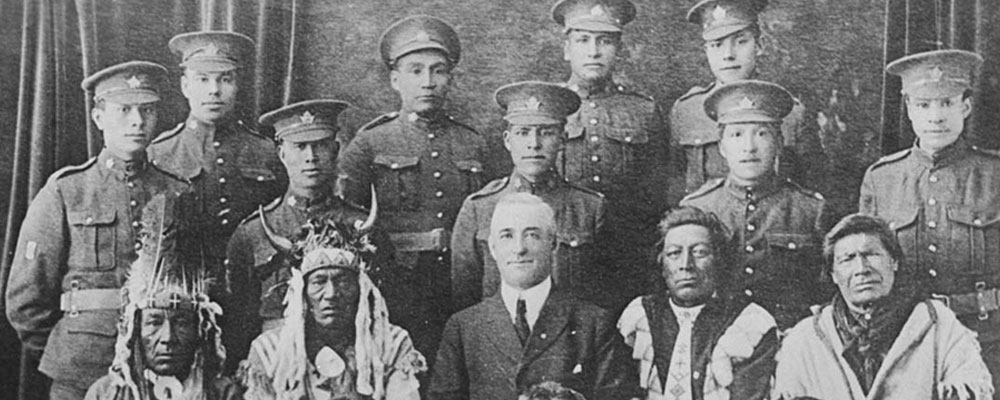

II. Before the War: The Making of a Hunter

Long before Europe burned, Francis Pegahmagabow learned a different discipline on the shores of Georgian Bay in Ontario. Born into the Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) world, he was raised not as a soldier but as a hunter—one whose survival depended on patience, awareness, and respect for life taken.

Hunting, in Ojibwe tradition, was not conquest. It was relationship.

To hunt successfully meant learning the wind’s language, the way animals moved through snow and forest, the difference between noise and silence that mattered. It meant understanding that the land watched you as closely as you watched it.

These lessons were not metaphorical. They were practical, spiritual, and embodied. They shaped the way Pegahmagabow moved, breathed, waited.

When war came, those lessons crossed an ocean with him.

III. A Soldier the Army Did Not Know How to Understand

When Pegahmagabow joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force, the army trained him like any other infantryman. Drill. March. Fire. Obey.

But soon, his commanders noticed something different.

He could lie motionless for hours—sometimes more than half a day—without shifting. He navigated no man’s land at night as if following invisible paths. He anticipated enemy movement before scouts confirmed it.

Most unsettling of all: he rarely missed.

Officially credited with 378 confirmed kills, Pegahmagabow remains among the deadliest snipers in military history. Unofficial estimates run far higher. Officers reviewing the numbers found them implausible. Records officers suspected clerical errors.

Yet the bodies kept appearing where Pegahmagabow said they would.

The men in his unit gave him a name spoken quietly, almost respectfully:

The Spirit Sniper.

IV. The Rifle Everyone Else Abandoned

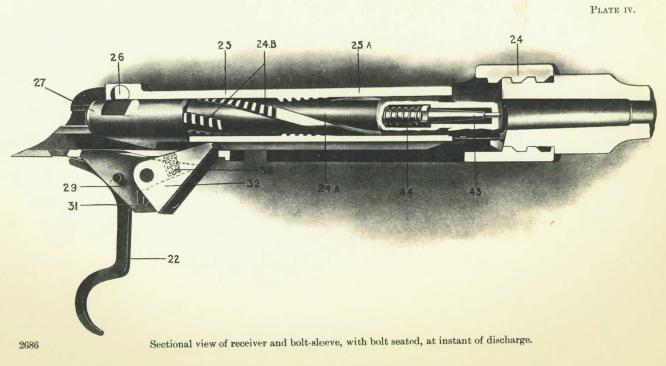

Pegahmagabow’s weapon only deepened the mystery.

While most Canadian soldiers discarded the Ross rifle at the first opportunity—complaining of jamming bolts, overheating barrels, and catastrophic failures—Pegahmagabow refused to part with his.

The Ross rifle was infamous. Armorers cursed it. Soldiers distrusted it. Historians would later catalog its design flaws in detail.

Yet in Pegahmagabow’s hands, it performed with uncanny consistency.

At distances exceeding 800 yards—sometimes approaching a mile—he struck targets others deemed unreachable. Wind, drop, fog, failing light: none seemed to matter.

When questioned, Pegahmagabow offered no technical explanation.

“This rifle,” he said, “is an extension of my spirit.”

V. The Battle of Passchendaele: Where the Earth Drowned Men

At Passchendaele, where mud swallowed the living as readily as the dead, Pegahmagabow was tasked with eliminating a German sniper responsible for dozens of Canadian casualties.

The enemy’s position—a ruined church steeple nearly a mile away—seemed impossible.

Lieutenant observers protested. Ballistics tables insisted it could not be done. Even if the bullet reached the target, wind shear and drop would render it inaccurate.

Pegahmagabow listened. Then he prepared.

He offered tobacco to the earth. He adjusted his scope not only for distance and wind, but for time—the time it would take the bullet to travel, the time the enemy would remain visible.

When he fired, the figure in the steeple fell.

Witnesses described the moment in whispers. Some called it luck. Others refused to speak of it at all.

VI. Behind Enemy Lines: Seven Shots Before Dawn

In the war’s later stages, intelligence warned of a massive German offensive. Reinforcements were moving. Commanders were gathering behind the lines.

Stopping the attack required eliminating its architects.

Pegahmagabow volunteered.

Under cover of darkness, he crawled through no man’s land, navigating by instinct and stars. By dawn, he lay concealed near a commandeered farmhouse serving as a German command post.

Before firing, he opened his rifle.

Inside the stock—hollowed in a way no standard issue weapon should have been—he rearranged sacred items: feathers, tobacco, carved wood, and a small bundle wrapped in red cloth.

Then he fired.

Seven shots.

Seven officers.

When German soldiers swarmed the area, an unnatural fog rolled in, obscuring vision to mere yards. Pegahmagabow vanished into it.

The offensive never came.

VII. After the War: A Hero Without a Parade

When the war ended, Pegahmagabow returned to Canada quietly. Unlike many of his white counterparts, he received little public recognition. No grand parade welcomed him home.

Instead, he fought a different battle—advocating for Indigenous rights, veterans’ recognition, and the dignity his service had not secured.

His rifle, however, did not fade into obscurity.

VIII. The Examination That Shocked Experts

After Pegahmagabow’s death in 1952, his rifle entered the collection of the Canadian War Museum.

Weapons specialists approached it with expectation. Surely, they thought, some hidden mechanical modification explained the legend: a retooled bolt, a precision barrel, an altered trigger.

They disassembled the rifle carefully.

They found none of that.

Instead, inside the stock, they discovered what Pegahmagabow had placed there decades earlier:

A pouch of tobacco

Owl and hawk feathers

A carved wooden totem

And most startling of all—a human tooth wrapped in red cloth

Records later confirmed it was Pegahmagabow’s own tooth, removed after being damaged in battle.

In Ojibwe belief, keeping a part of oneself with a weapon forged an unbreakable bond between warrior and tool.

From a mechanical standpoint, the rifle was unchanged.

From a cultural one, it was alive.

IX. The Unanswered Question

Ballistics experts examined the data. Nothing in physics explained Pegahmagabow’s consistency with a flawed weapon under battlefield conditions.

Some dismissed the contents of the rifle as superstition.

Others—especially those who had watched him shoot—hesitated.

One elderly officer, asked decades later if he believed in magic, answered carefully:

“I believe I saw a man who understood the wind, the earth, and himself better than anyone I ever met.”

X. Between Science and Spirit

Modern snipers now achieve kills at distances Pegahmagabow could scarcely imagine, aided by computers, laser rangefinders, and precision engineering.

Yet his legend persists.

Not because of the numbers alone—but because they challenge our assumptions.

What if mastery is not only technical?

What if belief, discipline, and worldview shape performance as profoundly as steel and powder?

When investigators looked inside Pegahmagabow’s rifle, they expected engineering.

What they found instead was a philosophy.

Epilogue: What Remains

Today, Francis Pegahmagabow’s rifle rests behind glass, silent and inert. Yet the question it poses remains alive.

Was it skill?

Training?

Spiritual connection?

Or something that emerges only when a human being is fully aligned with purpose?

Perhaps the truth exists in that narrow space between science and faith—where a man can place a feather and a tooth inside a rifle and turn a flawed weapon into history.

Some stories, after all, are not meant to be solved.

They are meant to be remembered.