Summer 1943. Sicily.

Before the first American soldier ever set foot on the island, a judgment had already been made. In the minds of Britain’s senior commanders, the United States Army was not yet a force meant to win wars. It was large, enthusiastic, well supplied—and amateur. Useful for holding ground. Useful for guarding flanks. But not the instrument that would deliver decisive victories.

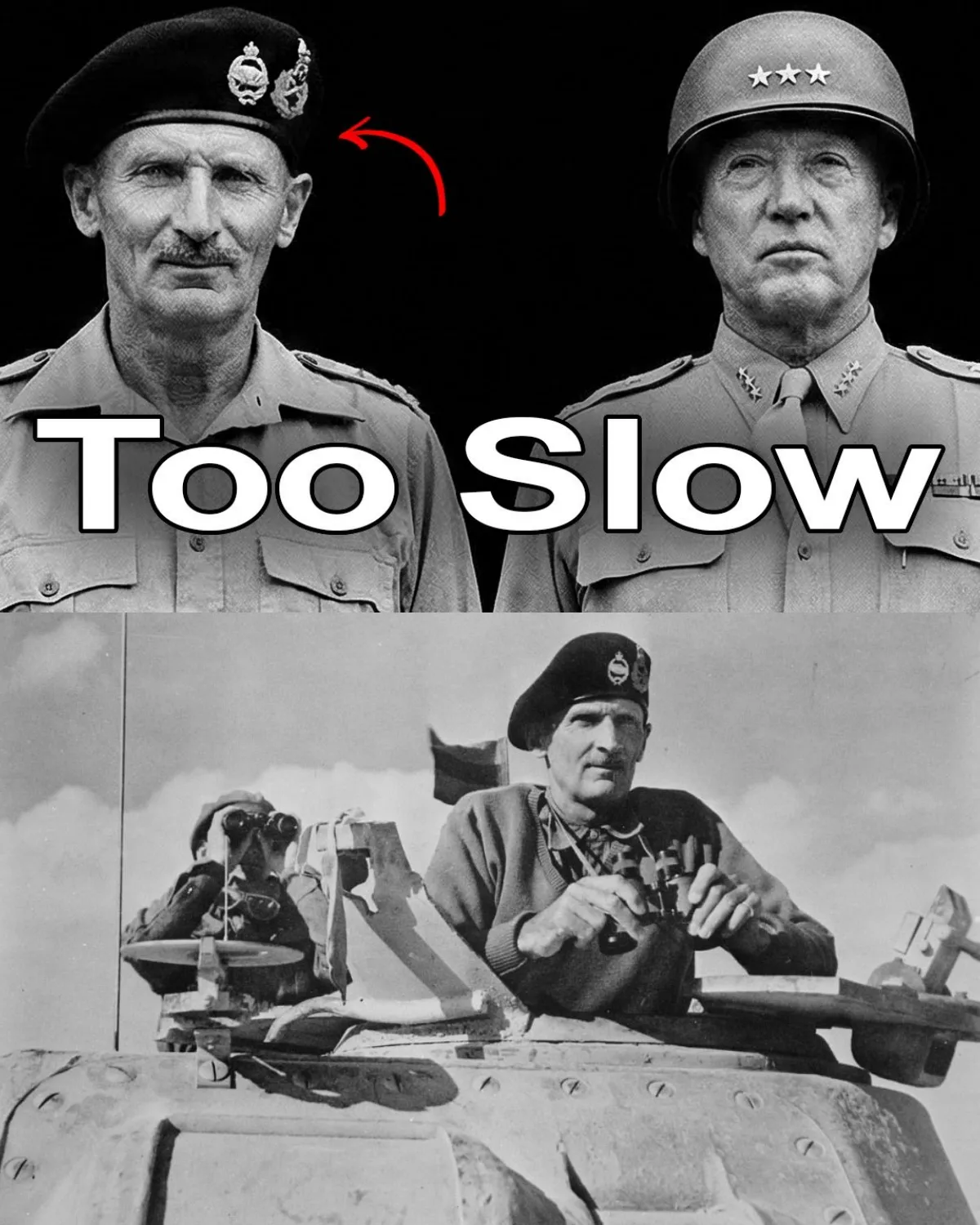

Bernard Law Montgomery believed this absolutely. And the plan for Sicily reflected it.

Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily, was supposed to be the proving ground for the Anglo-American partnership in Europe. In practice, it was designed as a British showcase. Montgomery’s Eighth Army would take the starring role. The Americans would learn by watching.

The campaign was planned under General Harold Alexander, a British officer who trusted Montgomery completely. At Alexander’s headquarters, British voices dominated every discussion. Of more than one hundred sixty staff officers, barely a dozen were American. This was not a partnership of equals. It was a classroom, and the Americans were not expected to graduate.

The operational design made the hierarchy unmistakable.

Montgomery’s Eighth Army would land on Sicily’s southeastern coast and advance straight up the island’s eastern flank. His objective was Messina—the gateway to mainland Italy. The road to it was direct, paved, and fast. Control Messina, and you controlled Sicily.

Patton’s Seventh Army was given a different mission. Land to the west. Protect Montgomery’s left flank. Prevent German counterattacks. Guard duty. Support. Stay out of the way.

The assumption was clear: Montgomery would fight the real battles. The Americans would provide insurance.

Montgomery estimated it would take six to eight weeks to reach Messina. The advance would be careful, methodical, textbook. Build overwhelming force. Avoid unnecessary risks. Minimize casualties. It was the same formula that had worked in North Africa. And it ensured one thing above all else—Montgomery would arrive as the conqueror.

When Patton saw the plan, he understood immediately what it meant.

The Americans were being sidelined.

And Patton had no intention of allowing Sicily to become a British victory parade that cemented American inferiority.

The insult became explicit when Montgomery seized Route 124—the best road on the island. Originally assigned to both armies, it was suddenly declared exclusive to the British. Montgomery claimed logistics demanded it. Two armies on one road would cause confusion, he said.

But everyone understood the truth. Route 124 led directly to Messina. Whoever owned it owned the victory.

Alexander approved the change.

American units that had already advanced inland were forced to turn around and march back to the coast, kicking up dust, burning energy, and swallowing humiliation. They were not being redirected by necessity. They were being moved aside.

Patton was furious. This was not coalition warfare. It was condescension.

So Patton studied the map again.

If the Americans couldn’t use the eastern road, they would take the western one. And if they moved fast enough—much faster than doctrine allowed—they could still reach Messina first.

It was not in the plan.

It was not authorized.

And Patton did not care.

July 10th, 1943.

Allied forces land on Sicily. The landings succeed. Both armies secure their beachheads. Montgomery begins his deliberate advance up the eastern coast. Syracuse falls. Augusta follows. Progress is steady, cautious, professional.

Patton’s Seventh Army does exactly what it was told. It guards the flank. It waits. And it wastes time.

By mid-July, it is obvious that there is no serious German threat in western Sicily. Patton goes to Alexander with a proposal. Let the Americans take the west. Capture Palermo. Turn east. Advance on Messina from the opposite direction.

Alexander hesitates. That was not the plan. But he cannot ignore reality. The Americans are idle. Montgomery is slow. Alexander gives Patton vague permission—reconnaissance in force. Exploit opportunities if they arise.

Patton takes it as authorization.

When a later order arrives telling him to stop, his chief of staff reports the message was garbled and requests clarification. The clarification arrives too late.

Patton has already committed.

July 19th, 1943.

Patton launches one of the most audacious advances of the war. Palermo lies more than one hundred miles away through mountains, poor roads, and terrain Montgomery’s staff said would take weeks to cross.

Patton gives his troops seventy-two hours.

They move day and night. Engineers blast roads out of rock. Tanks bypass resistance instead of reducing it. Infantry marches at a punishing pace—the “Truscott Trot”—five miles per hour through heat and dust. It is not a march. It is a lunge.

Italian defenses collapse under the shock. Garrisons surrender before they can organize. American columns appear where no one expects them.

On July 22nd, Palermo falls.

One hundred miles in three days.

The message is unmistakable. American forces are not amateurs. They are fast. Aggressive. Relentless.

Montgomery dismisses it publicly. Palermo is irrelevant, he says. Messina is the real objective. But privately, he understands the danger.

Patton is now turning east.

And suddenly, Sicily becomes a race.

Montgomery’s Eighth Army is bogged down near Catania, grinding against prepared defenses that German engineers had time to build while he advanced cautiously. Every pause strengthens the enemy. Every day lost gives Patton time.

Both commanders know the truth, even if headquarters pretends otherwise. Whoever enters Messina first wins the campaign’s narrative.

Patton drives his men harder. He launches improvised amphibious landings along the northern coast, leapfrogging German positions. Some nearly end in disaster. One battalion is almost annihilated. But they work.

Montgomery, furious, adopts the same tactics too late.

By mid-August, the outcome is clear.

August 17th, 1943.

American troops enter Messina at dawn. The Germans are gone. The last Axis forces slipped across the strait during the night. There is no battle. None is needed.

The race was never about fighting Germans.

It was about arrival.

American flags go up over the port. Patton arrives hours later and ensures every correspondent sees who got there first. When British patrols arrive later that morning, they find American soldiers already holding the city—relaxed, smoking, in possession of the keys.

Montgomery avoids the ceremony.

The humiliation is complete.

The British press tries to spin it. The Americans had an easier route. Messina wasn’t decisive. The real fighting was elsewhere. But no one who understands warfare believes it.

German commanders draw their own conclusions. Montgomery is professional, they say. Predictable. Easy to plan against. Patton is dangerous. Impossible to anticipate. A continuous emergency.

Defending against Montgomery is a calculation.

Defending against Patton is chaos.

Sicily changes everything.

From that moment on, the United States Army is no longer Britain’s junior partner—not in manpower, not in industry, and no longer in battlefield competence. But the victory comes at a cost. While the Allies race each other, the Germans evacuate more than one hundred thousand troops to mainland Italy.

The enemy escapes while the allies compete.

It is a triumph of momentum—and a failure of unity.

But history remembers Sicily for one thing above all else. It was the moment American forces proved they did not need to be managed, slowed, or sidelined. And it was the moment Bernard Montgomery learned that George Patton would never again accept a supporting role.