January 7th, 1945. Belgium.

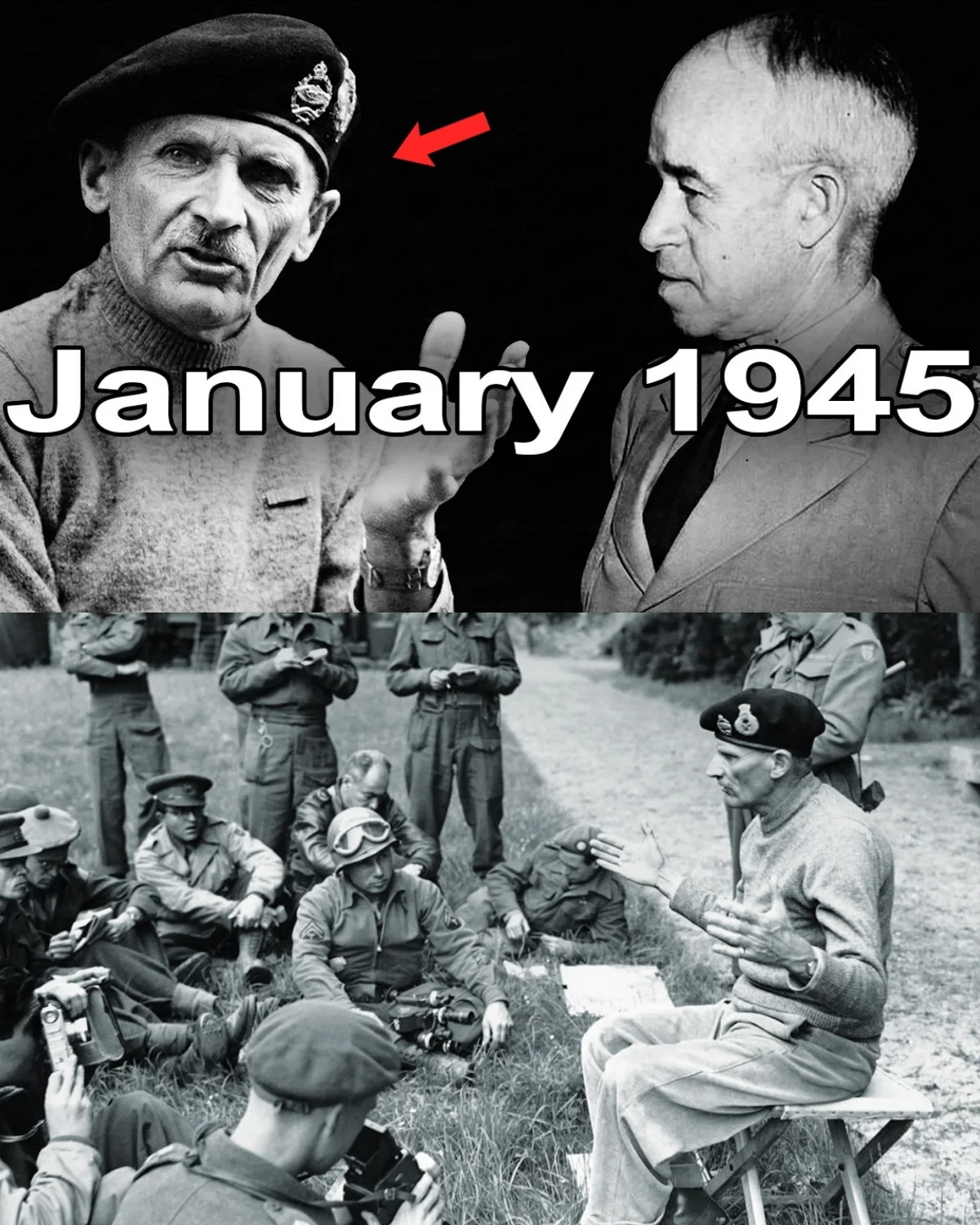

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery stands behind a simple podium inside his headquarters. Outside, winter grips Europe. Inside, the war’s most fragile alliance is about to be tested not by German artillery, but by words. Montgomery called this press conference himself. No one forced it. No one suggested it. He wanted, as he put it, to “set the record straight.”

The Battle of the Bulge was over. The German offensive had been stopped. The crisis had passed. Now came the story of what had happened—and who would be remembered for it.

Montgomery wears his trademark beret, decorated with two badges, a deliberate symbol of experience and authority. He appears relaxed. Confident. Almost pleased. British and American correspondents sit with notebooks open, expecting a conventional briefing: enemy losses, stabilized lines, cautious praise of Allied cooperation. What they are about to hear will come close to tearing the Allied command apart.

Within twenty-four hours, General Omar Bradley will be drafting his resignation.

Within forty-eight hours, Winston Churchill will be scrambling to contain a political disaster.

Within a week, the command structure in Europe will be hanging by a thread.

To understand why, you have to understand what the Battle of the Bulge meant to the men who fought it.

December 16th, 1944.

Before dawn, the German army launches its final gamble in the West. Twenty-nine divisions smash into American lines in the Ardennes forest. Snow. Fog. Silence. The attack achieves total surprise. American positions are thin. Communications break down. Entire units are overrun or scattered in the first forty-eight hours. A sixty-mile bulge is driven into the Allied front, threatening Antwerp and the Allied supply lifeline.

It becomes the largest and bloodiest battle the United States Army will ever fight. Nearly ninety thousand American casualties in six weeks. Men freeze in foxholes. Columns retreat through choking snow. Bastogne is surrounded. The situation is desperate.

On December 20th, Dwight D. Eisenhower makes a decision that will later ignite a firestorm. The German penetration has split American forces in two. Communications between General Bradley’s headquarters and northern units are unreliable. Eisenhower temporarily places Allied forces north of the bulge under Montgomery’s command—including two American armies that Bradley has led since Normandy.

Bradley explodes in anger. He warns Eisenhower this will be seen as humiliation. A vote of no confidence in American leadership. Politically explosive back home. Eisenhower listens—and overrules him. The decision is operational, he says. Montgomery is closer. He can stabilize the line.

Bradley understands what this looks like. Americans take the blow. A British general arrives to clean up the mess.

Montgomery arrives at First Army headquarters like a man boarding a sinking ship. Later, he will describe what he found as chaos and confusion. He reorganizes positions, pulls units back, prepares reserves. He does competent work. The northern shoulder holds.

But the battle is not won in Montgomery’s headquarters.

It is won by American soldiers.

On December 19th, three days into the crisis, George Patton executes one of the most extraordinary maneuvers of the war. He disengages three divisions, pivots them ninety degrees north, and drives them through winter roads toward Bastogne. On December 26th, Patton breaks through and relieves the 101st Airborne. By early January, American forces are crushing the bulge from north and south.

The Germans are beaten. The crisis is over.

That is when Montgomery decides to speak.

His staff advises against it. The Americans are sensitive. Emotions are raw. Let Eisenhower handle the public story. Montgomery dismisses the warnings. He believes he deserves credit. He believes the British public deserves recognition.

On January 7th, he begins calmly. He describes the German offensive. He explains how he assumed command in the north. Then he utters a sentence that causes American correspondents to stiffen in their chairs.

“The battle has been most interesting. Possibly one of the most interesting and tricky battles I have ever handled.”

Handled.

Not fought by. Not endured by. Handled—by him.

He continues. He explains how he tidied the battlefield. How he sorted things out. How he positioned reserves and planned counterattacks. Every action is described in the first person. Every success flows upward to Montgomery.

Then comes the implication that detonates the room.

He describes British forces fighting on both sides of American troops who “had suffered a hard blow.” The meaning is unmistakable. The Americans were overwhelmed. The British stepped in. Montgomery saved the situation.

American reporters know exactly what this sounds like.

These are men whose readers include soldiers who have spent six weeks freezing, bleeding, and dying in the Ardennes. Men who held the line when everything broke. Men who fought without relief. And now a British general is telling the world that he rescued them.

It gets worse.

A reporter asks about Patton’s relief of Bastogne. Montgomery offers a brief acknowledgment. “Patton has done very well indeed.” Then moves on.

The British press erupts in celebration. Headlines declare that Montgomery saved the Americans. That British leadership rescued inexperienced allies. The tone is triumphant, almost gloating. After years of war and perceived subordination to American power, Britain embraces the story.

The American reaction is volcanic.

Correspondents file furious stories. Editorials condemn Montgomery’s arrogance. Military newspapers rage. Soldiers read his words and feel robbed. They fought the battle. They paid the price. And now someone else is taking credit.

Omar Bradley reads the reports in Luxembourg. He has endured Montgomery’s condescension for two years. This is the final insult. He writes his resignation. He will not serve under these conditions. Other generals quietly indicate they will follow him.

When Eisenhower learns of this, he understands the scale of the crisis. If Bradley resigns, Congress will explode. The American public will demand answers. The alliance itself could fracture.

Eisenhower begs for time. He calls Montgomery. He explains the damage. Montgomery is baffled. He insists he was praising American soldiers. He said it was a fine Allied picture. What was the problem?

Montgomery does not understand tone. He does not hear implication. He does not grasp psychology.

Winston Churchill understands immediately. On January 18th, he rises in Parliament and delivers a masterclass in damage control. He praises American leadership lavishly. He emphasizes American sacrifice. He makes it clear that the battle was overwhelmingly an American fight.

The message is unmistakable.

Montgomery issues a clarification. It is not an apology. It changes little. American commanders are unconvinced. Eisenhower finally extracts a promise: Montgomery will never again command American forces except in the most extreme emergency.

The alliance survives—but scarred.

Montgomery never fully understands what he did wrong. In his memoirs, he continues to portray himself as decisive. History is less kind. Modern historians agree: Montgomery stabilized a situation. He did not save the Americans. American soldiers saved themselves.

The press conference lasted less than an hour.

Its consequences lasted for decades.

It stands as a reminder that in war, words can wound alliances as deeply as bullets—and that sometimes the most important skill a leader can possess is knowing when to remain silent.