Mid-February 1943. Tunisia.

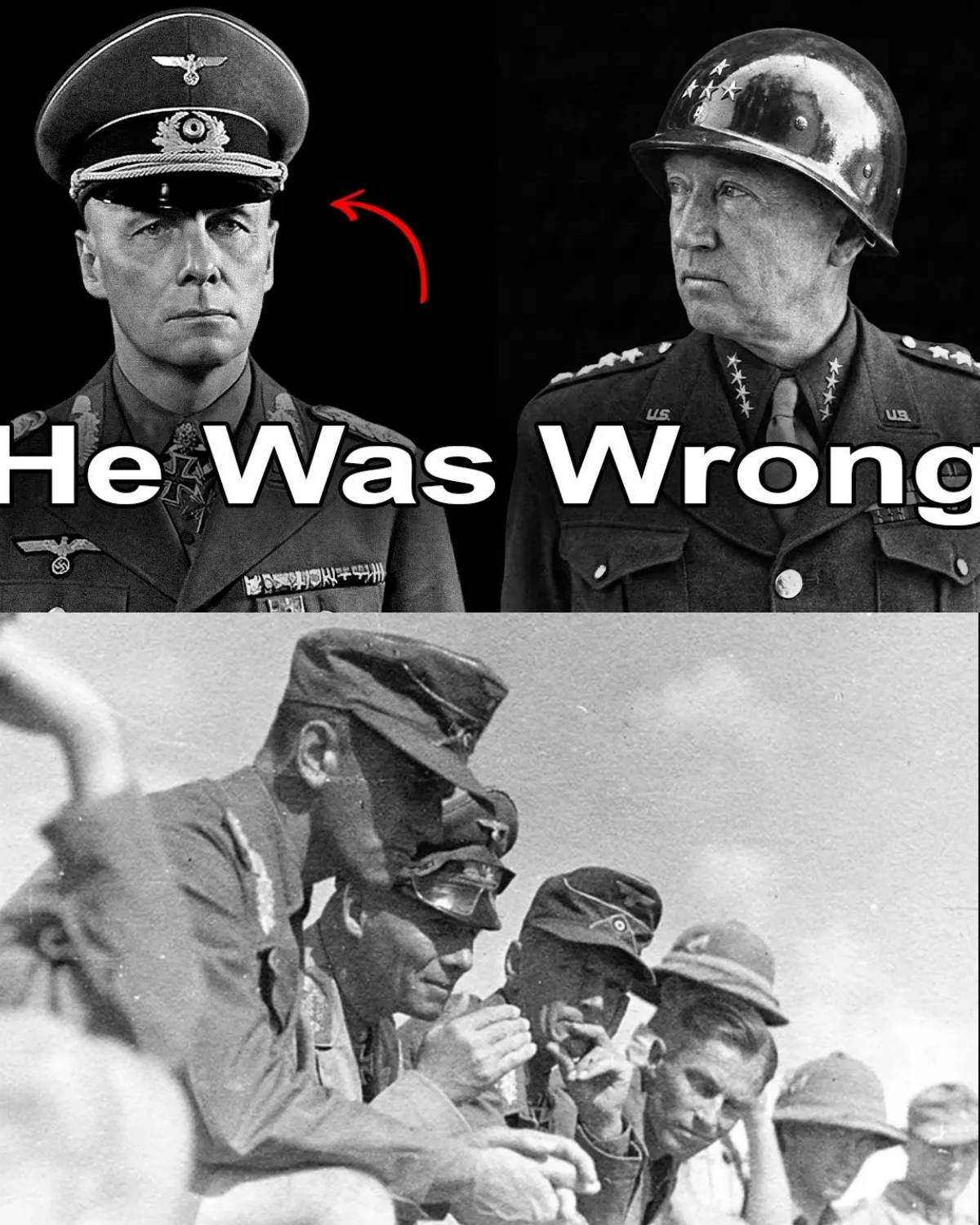

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel sits alone in his command post near the Tunisian border, pen in hand, writing to his wife. Outside, German troops celebrate a victory that feels familiar, almost routine. Inside, Rommel is not celebrating. He is thinking.

Days earlier, his forces smashed through American positions at Kasserine Pass. The battle had been decisive. American units collapsed under pressure. Entire battalions surrendered. Equipment was abandoned in neat lines along retreat routes. Over six thousand American casualties in less than a week. To Rommel, it looked painfully familiar—France in 1940, the early Soviets in 1941. An army that had not yet learned how to fight.

Rommel’s letter is blunt. He writes that the Americans are soft. Poorly trained. Led by officers who make mistakes no professional European army would tolerate. He does not write this with contempt. He writes it with certainty. What he has just witnessed confirms everything German doctrine predicts about inexperienced forces under armored pressure.

Rommel believes he is watching morale collapse in real time.

He tells his wife that if Germany attacks again quickly—before the Americans adapt—it could drive them into the sea. He sends the assessment to Berlin. The recommendation is clear: strike immediately. Do not give them time.

Rommel’s confidence is not prejudice. It is analysis.

At Kasserine, American command had failed at every level. Units were badly positioned. Radio discipline collapsed. Infantry and armor operated independently. When pressure mounted, withdrawals happened without coordination, creating panic that spread faster than orders.

The American corps commander had built his headquarters dozens of miles behind the front, issuing instructions without seeing the battlefield. German intelligence notes the pattern: American soldiers fight bravely when cornered, but leadership is amateur. This is an army learning war the hard way—against Germany’s best.

Rommel calculates that it will take the Americans at least six months to fix leadership failures. A year to develop effective doctrine. If Germany strikes again in March, the outcome will mirror Kasserine. German armored doctrine has proven itself repeatedly: concentrate force, break through, exploit speed. It has destroyed French, British, and Soviet formations. The Americans have shown they fight defensively, waiting to be attacked.

Berlin agrees. One more offensive should finish them.

Then something changes.

In early March, German intelligence reports a command shift. George S. Patton has taken over the American II Corps—the same corps that collapsed at Kasserine. When Patton arrives, the atmosphere changes instantly. He arrives loudly. Sirens. Convoys. Ivory-handled pistols. Theatrics with purpose.

Patton doesn’t inspire with speeches. He imposes order. Discipline becomes absolute. Uniforms are enforced in desert heat. Salutes are mandatory. Officers are fined publicly. Hesitation is punished. Aggression is rewarded.

German commanders dismiss it. Discipline cannot fix doctrine in three weeks.

Rommel, already ill and preparing to leave Africa, reviews plans for another offensive near El Guettar. The assumptions are logical. The Americans will defend fixed positions. Under pressure, they will retreat. Three weeks is not enough time to change an army.

On March 23rd, German forces attack.

Everything goes according to plan—until it doesn’t.

At dawn, German armor advances confidently. Terrain is favorable. Visibility is clear. Then American artillery fires. Not scattered rounds. Not ranging shots. Perfectly synchronized barrages. Multiple batteries striking the same target at the same second.

This is new.

German units take direct hits. Communications report heavy losses. The Americans are not suppressed. They are coordinated.

Tank destroyers open fire from concealed positions. German armor takes flank shots. The Americans are not defending obvious lines—they have created overlapping kill zones. When pressure builds, they withdraw deliberately to prepared positions, then resume fighting.

They are not running.

German radio intercepts pick up calm American communications. Clear orders. Precise coordination. This is not Kasserine.

By midday, the German advance stalls. Casualties mount without progress. The breakthrough never comes. German commanders call off the attack.

They begin asking questions.

The Americans have not received new equipment. They have not received months of training. The transformation happened in twenty-one days.

Patton’s changes were simple and ruthless. He purged weak leadership. He enforced aggressive doctrine. He taught every unit that defense meant counterattack. Artillery became the decisive arm—overwhelming, precise, unstoppable. Hesitation disappeared.

Rommel’s revised assessments warn German commanders that American forces are changing faster than any opponent Germany has faced. The warning arrives too late.

Within months, American forces help destroy the Axis army in North Africa. In Sicily, they race past British forces. In France, Rommel faces them again—no longer as amateurs, but as a machine designed for relentless advance.

After the war, German generals describe the transformation with disbelief. Americans learn faster than any army they encountered. Their artillery coordination is unmatched. Their aggression makes static defense impossible.

The army that broke at Kasserine is gone.

Rommel’s first judgment was logical—and wrong. Experience mattered less than leadership. Doctrine mattered more than tanks. Aggression mattered more than tradition.

Three weeks changed everything.

By the time German commanders accepted it, it was irreversible. The Americans were no longer tourists in uniform. They were professionals. And by the end of the war, they were the architects of Germany’s defeat.

The lesson was brutal and permanent.

The enemy you underestimate is not the one who beats you.

It’s the one who learns faster than you do.